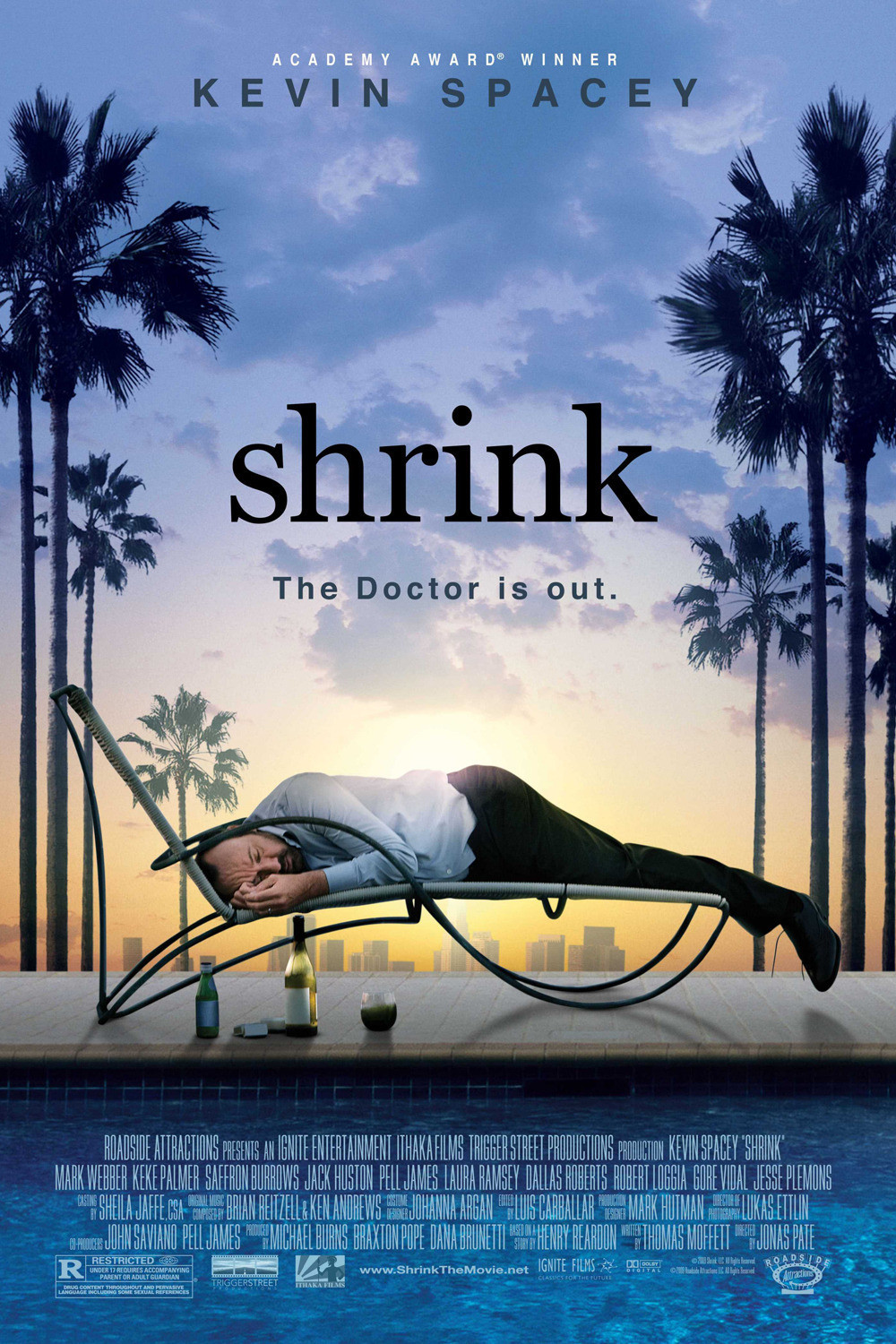

“Shrink” gives us a high-profile Los Angeles psychiatrist whose life has been reduced to smoking as much pot as he possibly can. If the movie contains a surprise, it’s that he doesn’t find his way to cocaine. Kevin Spacey brings another of his cynical, bitter characters to life–very smart, and fresh out of hope–but the movie doesn’t give him much of anywhere to take it.

The idea of rich, famous, drug-addled Hollywood flotsam is not precisely original, and this sort of story has rarely been more strongly told than in “Hurlyburly” (1998), with Sean Penn as a cokehead and Spacey himself as a bemused, supercilious witness to the wreckage. As for the behind-the-scenes Hollywood stuff, you can’t much improve on Altman’s “The Player.”

What director Jonas Pate and his writer, Thomas Moffett, do is sidestep deep characterization and bring in a rather conventional assortment of clients for Spacey’s shrink, named Henry Carter. We meet a movie star past his sell-by date (Robin Williams, unbilled), who thinks his problem is sex addiction, although Henry assures him it is alcoholism (the sex addict’s running mate). Dallas Roberts plays Patrick, an agent driven by hyperactive compulsions; Patrick’s assistant Daisy (Pell James), is preggers; Shamus (Jack Huston), an Irish actor who is an alcoholic just for starters, and the actress Kate (Saffron Burrows), is a trophy wife who finds her husband’s trophy shelf is not yet complete.

These characters are intriguing in their own ways, especially when we sense Williams restraining himself from bolting headlong into his descriptions of sexual improbabilities, but each one is essentially a walk-on act, and even when their lifelines cross it seems an event in the screenplay, not their lives.

One actress who does create a free-standing character is Keke Palmer (Jemma), mourning her mother, finding refuge in the movie revivals she attends as a form of escape. Palmer was the young star of “Akeelah and the Bee” (2006), and is still only 16; remember her name.

Directing emotional traffic amid these problems, the Spacey character is coming to pieces. His wife has recently committed suicide, he can barely focus on his clients, and although he’s excellent at spotting addiction in others, he rationalizes his own. It takes his father (Robert Loggia) to talk straight to him, and he is stunned to find himself the recipient of an intervention.

Working within the range we frequently find him, Kevin Spacey is a master. Yes, there is a pattern to many of his roles, but there are characters he is suited to and others that would be improbable. Many critics find fault with him for not repeating “American Beauty” in every film, or maybe even for making it in the first place. I sense an acute intelligence at work. When he found few interesting Hollywood projects, he went to the London stage, took over management of the Old Vic, and reinvented himself. Why are some critics snarky toward such an actor? Is it the price they pay for trying?

That said, “Shrink” contains ideas for a film, but no emotional center. A group of troubled characters are assembled and allowed to act out, not to much purpose. Jemma, the young girl, is the most authentic, and Henry relates to her most movingly. Two actors have found something to dig into.