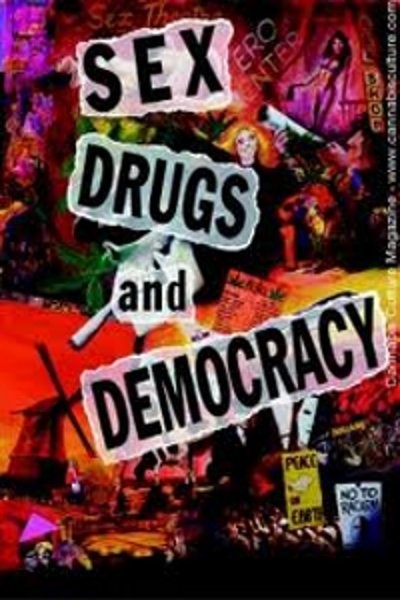

The country sounds, in fact, like a libertarian paradise, and the new documentary “Sex, Drugs and Democracy” plays like its campaign advertisement. The film visits with a series of judges, policemen, doctors, legislators and other members of the Dutch establishment, as well as with prostitutes, pot smokers, nude sunbathers and a “government hemp agronomist,” who argues enthusiastically that, acre for acre, hemp (a.k.a. marijuana) produces three times more paper than tree crops (publishers concerned about the rising cost of newsprint, please note).

“The laws are for us. We are not for the laws,” says Dr. Eddy Engelsman, the Dutch national director of Alcohol, Tobacco and Drug Policy. By creating a nation free of many of the laws that govern private behavior in the United States, the Netherlands has fewer drug deaths than other countries, fewer abortions, lower rates of teen pregnancy, a lower rate of AIDS and venereal diseases, one of the lowest murder and crime rates in Europe, the lowest imprisonment rate in the Western world and one of the highest life expectancies.

The law in the Netherlands seems more concerned with what you do to other people than with what you do to yourself. Prostitution, for example, is permitted as a contract between private individuals, and Dutch cities have regulated red-light districts. The government’s interest is in enforcing health guidelines and prohibiting pimping and criminal exploitation of the prostitutes (“We need to be sure a prostitute can leave the business if she wants to,” says a female legislator). By effectively decriminalizing many drugs, a police officer explains, the Dutch have removed the profit motive, thus making drugs less interesting to criminals and less glamorous to young people. “We don’t have a crack problem in the Netherlands because there is no stepping-stone from pot to hard drugs,” a lawmaker says.

The beat goes on: The Dutch have banned nuclear power. As a nation that has liberated half of its land mass from the sea, they are fanatic environmentalists. Small as their population is, it supplies 20 percent of the worldwide membership of Greenpeace. The national TV network includes the wildly popular “Gay Dating Game.” Watching this documentary, made by American filmmaker Jonathan Blank, would be inspiring if it were not just a little too good to be true. We know from other sources that the Netherlands, while a successful and enlightened nation, has its problems, too; one of them is the unwanted population of young foreign visitors, drawn every summer by rumors of cheap drugs, who sleep rough in the public places of Amsterdam and make the city more threatening for its inhabitants.

In Blank’s view, there is no other side to the Dutch solution, and his unwillingness to provide even a single dissenting voice is the weakest point of his documentary. We see a gay wedding in a Protestant church. Are there no clergy who have their doubts? We see a father who smiles about being his own son’s pot dealer. Are there parents who would not embrace this role? We hear from several prostitutes who extol the benefits of their lifestyle (most want financial independence and see it as just a job). Are there others who feel caught in a dead end? For an American viewer, the most enthralling parts of the film are those in which official government spokesmen come across like radical reformers. An Amsterdam police commissioner muses that the toleration of marijuana might be extended to heroin and cocaine. A “professor of gay studies” cites a recruiting ad placed by the police in a gay newspaper: “We like young men as much as you do!” A feminist defends pornography. A judge says the imprisonment rate is low “because the idea behind it is that you tolerate more variations in behavior.” The impression is of a nation operating free of the puritan heritage that informs many of the laws in the United States. At a time when Gingrich’s Republicans are promising a government which intrudes less into the lives of citizens, “Sex, Drugs and Democracy” is a reminder that his followers are fervently in support of some of the most intrusive laws.

The film suggests that you might reduce crime more by banning handguns than by increasing the prison population, that you could reduce drug use and its associated violence and corruption by decriminalizing it, that the United States has passed many laws about matters that are simply none of a government’s business. You have to venture into the libertarian fringe of the GOP to find any support for these notions.

“Sex, Drugs and Democracy” makes seductive arguments. It is too bad that Blank has made his film so monolithic, so one-sided and utopian in its portrait of Dutch life, that it raises questions even when it seems to be making sense.