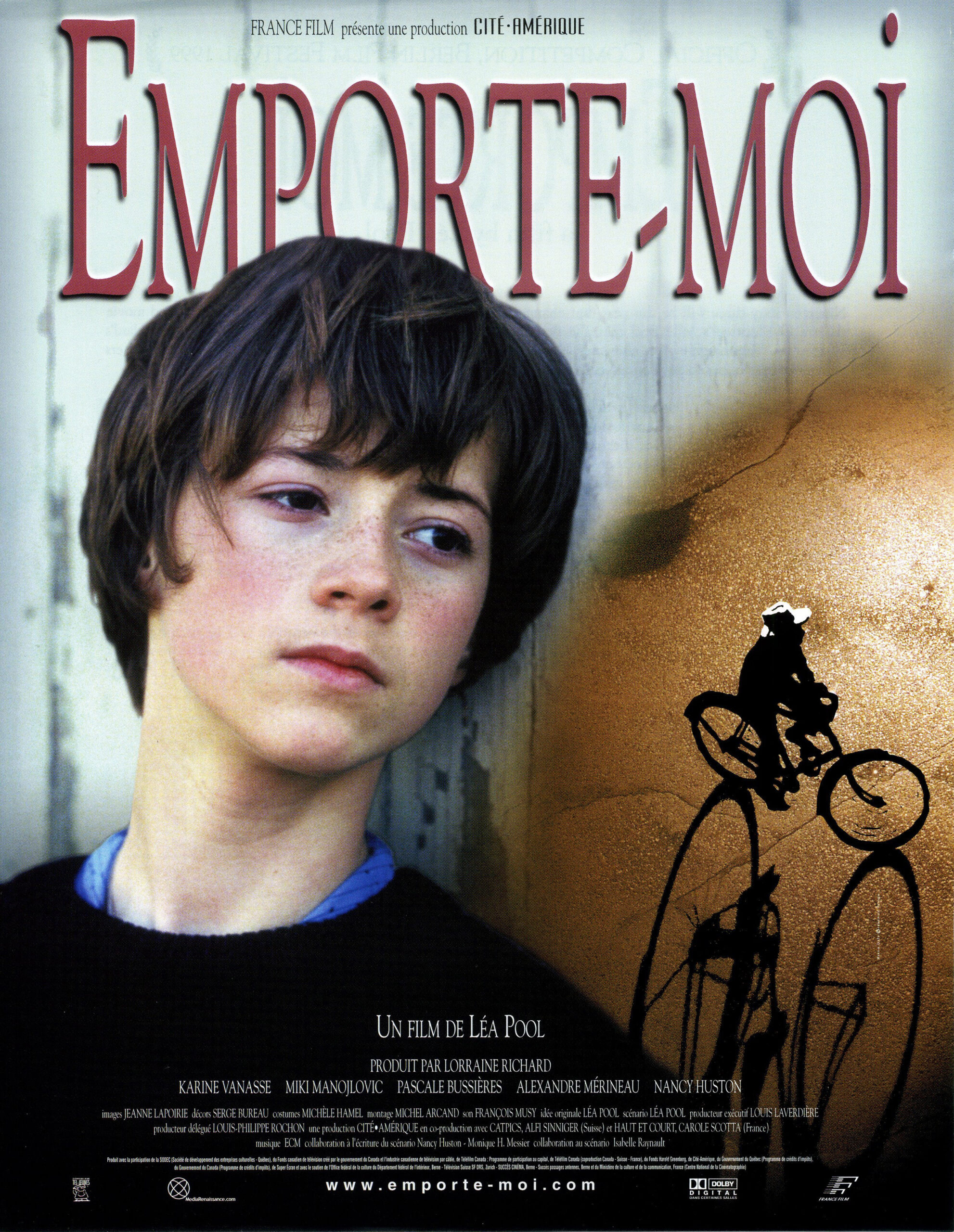

It is not reassuring when your father tells you, “Books are our only true friends.” Where does that leave you–or your mom, or your brother? And yet what he says may be worth hearing. Hanna, the heroine of “Set Me Free,” is a 13-year-old growing up in 1963 in Montreal. Her father is distant, disturbed, incapable of supporting his family and blames everyone but himself. Her mother is meek and suicidal. It’s up to Hanna to find her own way in life, and that’s what she does, at the movies.

Art can be a great consolation when you are a lonely teenager. It speaks directly to you. You find the right movie, the right song, the right book, and you are not alone. Books and movies are not our only friends, but they help us find true friends and tell them apart from the crowd.

One day in the rain, Hanna (Karine Vanasse) sneaks into a theater and sees Jean-Luc Godard’s “My Life to Live” (1962), where even the title is significant. It stars Anna Karina as an independent woman in Paris who leaves her husband and works as a prostitute to support herself. She keeps a distance from her clients; cigarettes form a wall between her and the world, and there is a famous shot where as a man embraces her, she sullenly blows out smoke.

Not the character you would choose as a role model for a 13-year-old girl. But Hanna is unhappy and confused. She has just had her first period and does not quite understand it. Her father is cold to her mother, her brother and herself, but then turns on the charm. There is no money in the household; her father (Miki Manojlovic) calls himself a writer but has published nothing, her mother (Pascale Bussieres) works as a seamstress, and the pawnbroker knows the kids by name. In this confusion, Hanna finds encouragement in the independent woman of the movie, who holds herself aloof, who is self-contained, who lets no man hurt her.

In Hanna’s life, there is some happiness. She idolizes her schoolteacher (Nancy Huston), who looks a little like Anna Karina. She makes a close school friend named Laura, and they share their first kiss together. Does this mean they will grow up to be lesbians? Maybe, but probably not; what it probably means is that they are so young that kissing is a mysterious activity not yet directly wired to sex and gender, and Laura offers tenderness Hanna desperately requires.

In school, like all the students, Hanna is called upon to stand up and give her life details. This leads to her admission that her parents are not married. Religion? “My father is Jewish, my mother is Catholic,” she says. And which is she? “Judaism passes the religion through the mother, which would make me Catholic, but Catholicism passes through the father, which would make me Jewish,” she says. “Myself, I don’t care.” Her father is a refugee from the Holocaust, an intellectual. Their apartment is filled with books. Her mother fell for him the first time she saw him and got pregnant at 16 with Paul, Hanna’s brother. When her father found this out two years later, he decided to care for them and soon Hanna was born. In a moment of revelation, Hanna’s father tells her that he was married in Europe, and that although his wife may have died in the camps, he has no proof and refuses to think of her as dead. Her mother also confides in Hanna that despite their troubles, she will never leave her husband: “I need him.” “Set Me Free” is set in 1963, when the films of the French New Wave would have been influential in French-speaking Quebec. In some of its details, it resembles Francois Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” which is about a young boy whose parents are unhappy, and who keeps a shrine to Balzac in his bedroom. Hanna’s Balzac is Karina in “My Life to Live.” Leaning against a wall, smoking insolently, not giving a damn, Karina provides not a role model but a strategy. It is not only possible to stand aside from the pain of your life, it can even become a personal style.

The movie gets a little confused toward the end, I think, as its writer and director, Lea Pool, tries to settle things that could have been left unresolved. Hanna’s tentative walk on the wild side is awkwardly handled. You walk out not quite satisfied. Later, when the movie settles in your mind, its central theme becomes clear. We grow by choosing those we admire and pulling ourselves up on the hand they extend. For Hanna, the hands come from her teacher, from her friend and from the woman in the movie she sees over and over. “I am responsible,” says Karina in the movie. “I am responsible,” says Hanna to herself. It is her life to live.