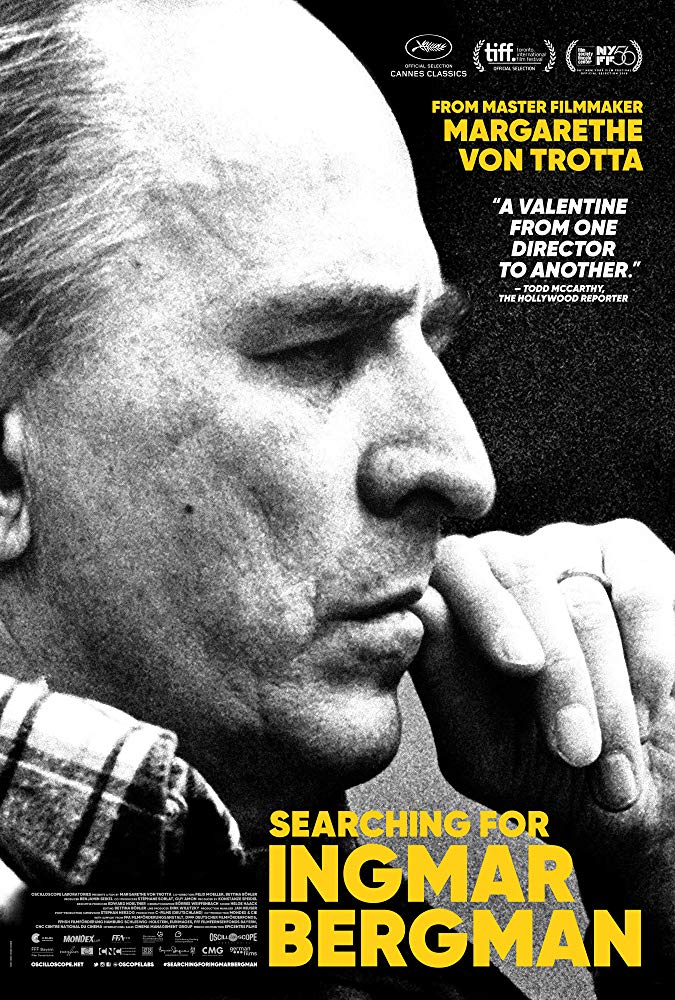

“Searching for Ingmar Bergman,” directed by German director Margarethe von Trotta, starts on a rocky beach, the same rocky beach featured in Bergman’s 1958 film “The Seventh Seal.” Von Trotta herself sits on a boulder, staring out at the waves and reciting, from memory, each shot from the opening sequence of “The Seventh Seal”: Max von Sydow sprawled on the shore, the horse in the water, the chessboard on a rock. Von Trotta speaks of what Bergman’s work meant to her, how revelatory it was at the time. “Searching for Ingmar Bergman” isn’t really a “search,” ultimately. It’s a pretty straightforward presentation of Bergman’s career, his films, his obsessions, his themes. Von Trotta walks over very well-trod ground, interviewing the usual suspects (although it’s always good to hear from them), listening to well-known stories told elsewhere. However, it’s still an engaging and accessible look at one of the most important figures in cinema.

Von Trotta started out as a cinephile inspired by the French New Wave, and then threw herself into the burgeoning film industry of post-War West Germany, first as an actress (appearing in films directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Volker Schlöndorff, two of the leading figures of the New Germany Cinema) and then as a filmmaker herself. She co-directed 1975’s “The Lost Honor Of Katharina Blum” with Schlöndorff, before moving on to a solo directorial career (“The Second Awakening Of Christa Klages,” “Marianne & Juliane”, “Rosa Luxembourg”). In 1994, Ingmar Bergman was asked by the Göteborg Film Festival to list his 11 all-time favorite films, and he included Von Trotta’s “Marianne & Juliane” (alongside “Rashomon“, “Sunset Boulevard,” “Passion of Joan of Arc” and “Andrei Rublev”). Von Trotta was the only woman on Bergman’s list.

“Searching for Bergman” features interviews with Bergman’s repertory of actors and collaborators, Liv Ullmann, Gunnel Lindblom (“It’s absolutely impossible to think what would I have become without him”), Katinka Faragó. Von Trotta interviews Bergman’s son Daniel, and his grandson (who gives a great image of Bergman screening “Pearl Harbor” and fast-forwarding over the love scenes). These interviews don’t hold many surprises, and they’re not really strung together with any rhyme or reason. Thankfully, Von Trotta avoids the tiresome “talking head” format by filming her interviews as conversations between herself and her subject. This gives the interviews room to breathe, room for spontaneity.

“Searching for Ingmar Bergman” comes alive as a work of true artistic exploration during her interviews with other film directors: Carlos Saura, Olivier Assayas, Ruben Östlund, Mia Hansen-Løve, each of whom provides a unique perspective on his influence on them. It’s fun to hear Östlund describing how Bergman’s “Scenes From a Marriage” inspired him, or Carlos Saura saying, “”Everyone is in love with Bergman’s actresses.” Assayas talks about how the “centrality of women” in Bergman’s work has influenced his own, and so on. Your mileage may vary, but I could watch artistic appreciation like this for hours.

It’s the year of Ingmar Bergman’s centenary. He died in 2007, leaving behind a daunting legacy—45 feature films over 6 decades, many of which are towering works of 20th century art. “The Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries,” “Cries and Whispers,” “Persona,” “Fanny and Alexander.” “Autumn Sonata.” There’s his bleak trilogy “Through a Glass Darkly,” “Winter Light,” and “The Silence” exploring the horror of God’s absence. Other films deepen our understanding of his complexities: “Summer with Monika”, “Smiles of a Summer Night”, “Dreams”, “A Lesson in Love”, “Virgin Spring”, “Shame.” His work requires the devotion of an acolyte, because there’s so much of it. Criterion is coming out with a gigantic box-set on November 20, including 39 of his 45 films, and a 250-page book of essays about him. Maybe this is all a little intimidating for someone new to Bergman. “Searching for Ingmar Bergman,” could serve as a good entry point.