“Runaway Train” is a reminder that the great adventures are great because they happen to people we care about. That was true of “The African Queen,” and of “Stagecoach,” and of “The Seven Samurai,” three movies that would otherwise seem to have little in common. And it is also true of this tale of two desperate convicts on a train that is hurtling through the snows of Alaska.

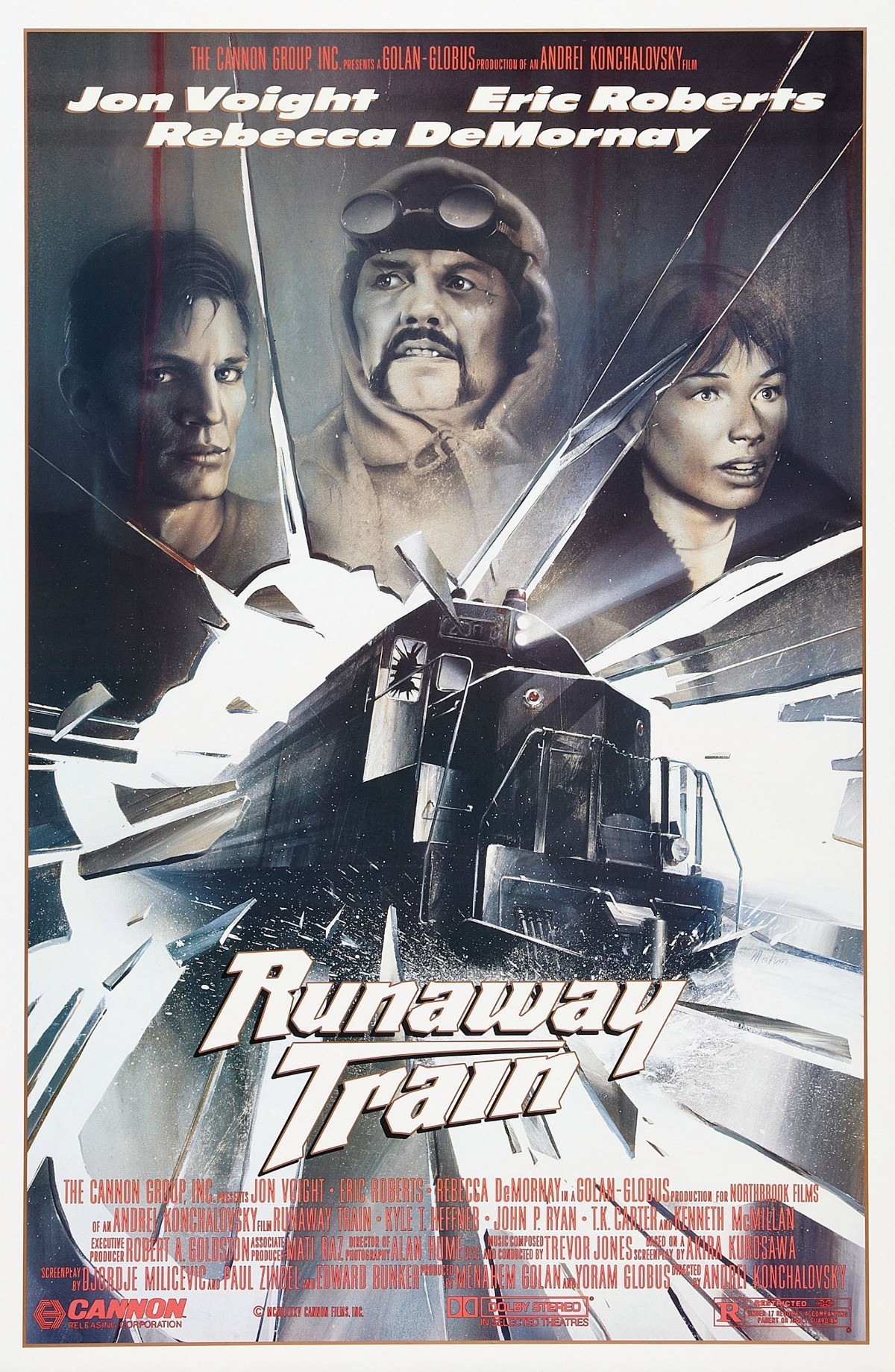

The movie stars Jon Voight and Eric Roberts, two actors with dramatically different styles. Voight is always internalized and moody; Roberts has a collection of verbal and physical tics that are usually irritating, and are sometimes meant to be. Here they are both correctly cast as two convicts in a maximum-security prison in Alaska who escape through a drain tunnel and then blunder onto the train that takes them on their hell-bound mission.

Voight plays Manny, a convict who is so distrusted by the warden that his cell doors have been welded shut for three years. “He’s not a human being – he’s an animal,” the warden says, and this is not just stock dialogue, but the thesis that the whole movie will test. Roberts is Buck, a trustie who works for the prison laundry. The warden is Barstow (Kyle T. Heffner), and he has a personal grudge against Manny.

In fact, he releases him from solitary in the wicked hope that Manny will try to escape – he’s done it before – and then Barstow can kill him.

The opening passages are intense, but somewhat routine; they’re out of the basic kit of prison movie cliches. Then the two convicts escape, and stumble by luck into one of the back cabs of a train that consists of four locomotives linked together. The train starts, the engineer suddenly collapses with a heart attack, and the epic journey has begun.

“Runaway Train” is based on an original screenplay by the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa, whose best movies use action as a means of studying character. (His recently released “Ran” retells “King Lear” in a samurai setting.) After some rewriting, “Runaway Train” was directed by Andrei Konchalovsky, the Russian emigre who figures so memorably (under a pseudonym) as Shirley MacLaine’s lover in her current best seller Dancing in the Light. He has given the story the kind of wildness and passion it requires; this isn’t a high-tech Hollywood adventure movie, but a raw saga that works close to the floor.

Once the train has started to move, the movie follows three threads. One involves the three people on the train (the two men discover after a while that a woman crew member, played by Rebecca DeMornay, is also on board and also powerless to stop the engines). The second thread involves the railway dispatchers, who quarrel over a computer system that may possibly have the ability to clear the tracks ahead of the runaway. The third involves the ferocious determination of Barstow, the warden, to track the train by helicopter, and to kill the men inside.

These elements might be enough to make “Runaway Train” a superior action movie. What makes it more than that are the dynamics inside the cab of the train. Voight is seen as a man who is intelligent enough to realize how desperate his situation is – because he has been caught not just in a physical trap, but also in a philosophical one. In an impassioned speech that may be the best single scene he has ever played, he tries to explain to Roberts how limited their choices are in life.

The Roberts character does not quite understand the story. He is a wild man of limited intelligence, and prison life has made him dangerous – he acts without regard for the consequences. When these two men are joined by a woman, it’s not just a plot gimmick; her role as an outsider gives them an audience and a mirror.

The action sequences in the movie are stunning. Frequently in recent movies, I’ve seen truly spectacular stunts and not been much excited, because I knew they were stunts. All I could appreciate was their smoothness of execution. In “Runaway Train,” as the characters try to climb along the sides of the ice-covered locomotives, as the train crashes through barriers and other trains, as men dangle from helicopters and try to kill the convicts, there is such a raw, uncluttered desperation in the feats that they put slick Hollywood stunts to shame.

The ending of the movie is astonishing in its emotional impact. I will not describe it. All I will say is that Konchalovsky has found the perfect visual image to express the ideas in his film. Instead of a speech, we get a picture, and the picture says everything that needs to be said. Afterward, just as the screen goes dark, there are a couple of lines from Shakespeare that may resonate more deeply the more you think about the Voight character.