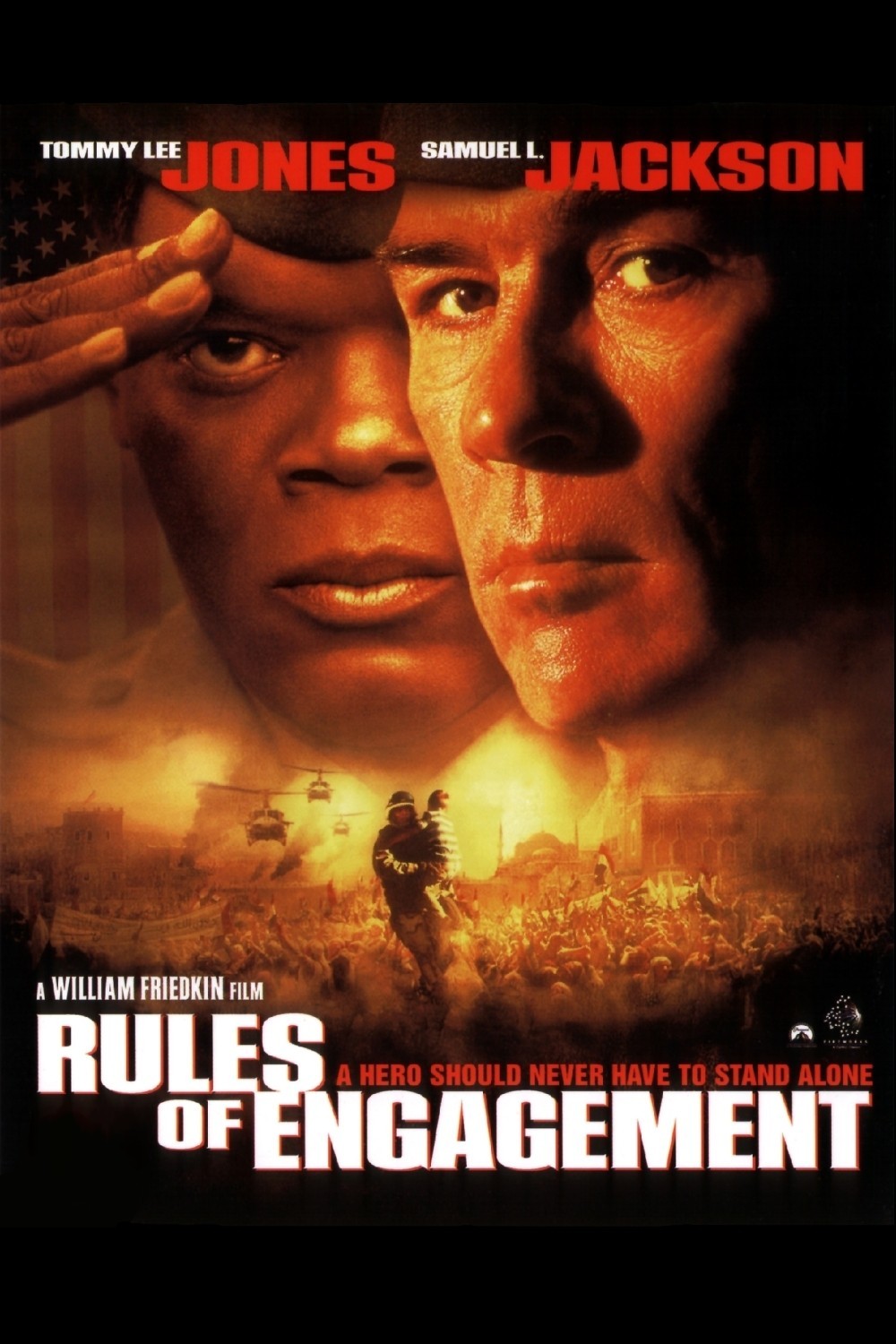

The film centers on a relationship forged throughout the adult lifetimes of two Marine colonels, Hays Hodges (Tommy Lee Jones) and Terry Childers (Samuel L. Jackson). They fought side by side in Vietnam, where Childers saved Hodges’ life by shooting an unarmed POW. That’s against the rules of war but understandable, in this story anyway, under the specific circumstances. Certainly Hodges is not complaining.

Years pass. Hodges, whose wounds make him unfit for action, gets a law degree and becomes a Marine lawyer. He also gets a divorce and becomes a drunk. Childers, much-decorated, is a textbook Marine who is chosen to lead a rescue mission into Yemen when the U.S. embassy there comes under threat from angry demonstrators.

Exactly what happens at the embassy, and why, becomes the material of a court-martial after Childers is accused of ordering his men to fire on a crowd of perhaps unarmed civilians, killing 83 of them. He persuades his old friend Hodges to represent him in the courtroom drama that occupies the second half of the film. Although the story marches confidently toward a debate about the ethical conduct of war, it trips over a villain who sidetracks the moral focus of the trial.

Remarkable, though, how well Jones, Jackson and director William L. Friedkin are able to sustain interest and suspense even while saddled with an infuriating screenplay. Little is done to provide the characters with any lives outside their jobs, and yet I believed in them and cared about the outcome of the trial. If their work had been supported by a more thoughtful screenplay, this film might have really amounted to something.

Some of the lapses can’t be discussed without revealing plot secrets. Here’s one that can. Hodges makes a fact-finding visit to Yemen, and sees children who were victims of Childers’ order to fire (the scene echoes one in “The Third Man“). He returns, drunk and enraged, and accuses Childers of lying to him. Childers punches him. Hodges fights back. They have a bitter brawl–two middle-aged men, gasping for breath–while we try not to wonder how a lame attorney can hold his own with a combat warrior. Finally, with his last strength, Hodges throws a pillow at Childers, and the two bloodied men start laughing. This works fine as an illustration of an ancient movie cliche about a fight between friends, but what does it mean in the movie? That Hodges has forgotten the reason for his anger? That it was not valid? Much depends, during the trial, on a missing tape that might show what really happened when the crowd was fired on. The tape is destroyed by the National Security Adviser (Bruce Greenwood), who tells an aide: “I don’t want to watch this tape. I don’t want to testify about it. I don’t want it to exist.” How do you get to be the National Security Adviser if you’re dumb enough to say things like that out loud to a witness? And dumb enough, for that matter, to destroy this particular tape in the first place–when it might be more useful to the United States to show it? Much is made in the movie of the Marines’ esprit de corps, of protecting the lives of the men under your command, of following a warrior code. Yet one puzzling closeup of Childers’ eyes during the Vietnam sequence supplies an undertow that influences our view of the character all through the movie: Is he acting as a good Marine or out of rage? This adds usefully to the suspense (movie stars are usually found innocent in courtroom dramas, but this time we can’t be sure). But eventually we want more of an answer than we get.

One entire subplot is a missed opportunity. We see the U.S. Ambassador (Ben Kingsley) and his wife and son as they’re rescued by Childers. Later we hear his testimony in court, and then there’s a scene between Hodges and the ambassador’s wife (Anne Archer). Everything calls for a courtroom showdown involving either the ambassador or his wife, but there isn’t one. Why set it up if you’re not going to pay it off? I ask these questions and yet admit that the movie involved me dramatically. Jones and Jackson work well together, bringing more conviction to many scenes than they really deserve. The fundamental problem with “Rules of Engagement,” I suspect, is that the filmmakers never clearly defined exactly what they believed about the issues they raised. Expert melodrama conceals their uncertainty up to a point, but at the end we have a film that attacks its central issue from all sides and has a collision in the middle.