Japanese animation, or “anime,” as its fans call it, is an enormous but almost invisible phenomenon in this country. There has never been a wide-platform U.S. release of an animated film from Japan, and even those few titles that have won acceptance (“Akira,” “My Neighbor Totoro,” “The Wings of Honneamise”) have played mostly in art houses–often as midnight shows. Most North Americans have no exposure at all to made-in-Japan animation except on TV cartoon programs–which, although they have their fanatic followings on campuses, don’t show the genre at its best.

In Japan, animation is not automatically considered entertainment for children and families. Adult themes, violence and sexuality are often dealt with in animated films, as in the incredibly popular comic books you see half the subway population reading every day. Walt Disney did a great service to animation by popularizing it at feature length, and his disciples continue to find enormous audiences for the art form, but the very success of Disney and its imitators has prevented the development of animation as a fully rounded art form.

So if that’s the case, where does anime thrive in North America? On video, mostly. Every video store has a shelf devoted to Japanimation, often under examination by intense young men who hold detailed conversations in what sounds like code. Stores devoted to comic books and trading cards all have shelves of video anime for sale. Almost every campus has an anime club, where even animated daytime kiddie serials are analyzed and deconstructed. Anime films are booked by campus film societies. There are lots of anime fanzines. And the Internet is crawling with hundreds of anime Web pages and thousands of newsgroup messages.

All of this is taking place out of sight of conventional entertainment channels, but occasionally one of the better feature-length films does find a theatrical booking. Two are in current release around the country: “The Ghost in the Shell,” which I’ll review soon, and “Roujin-Z,” which is playing as a midnight show at the Music Box.

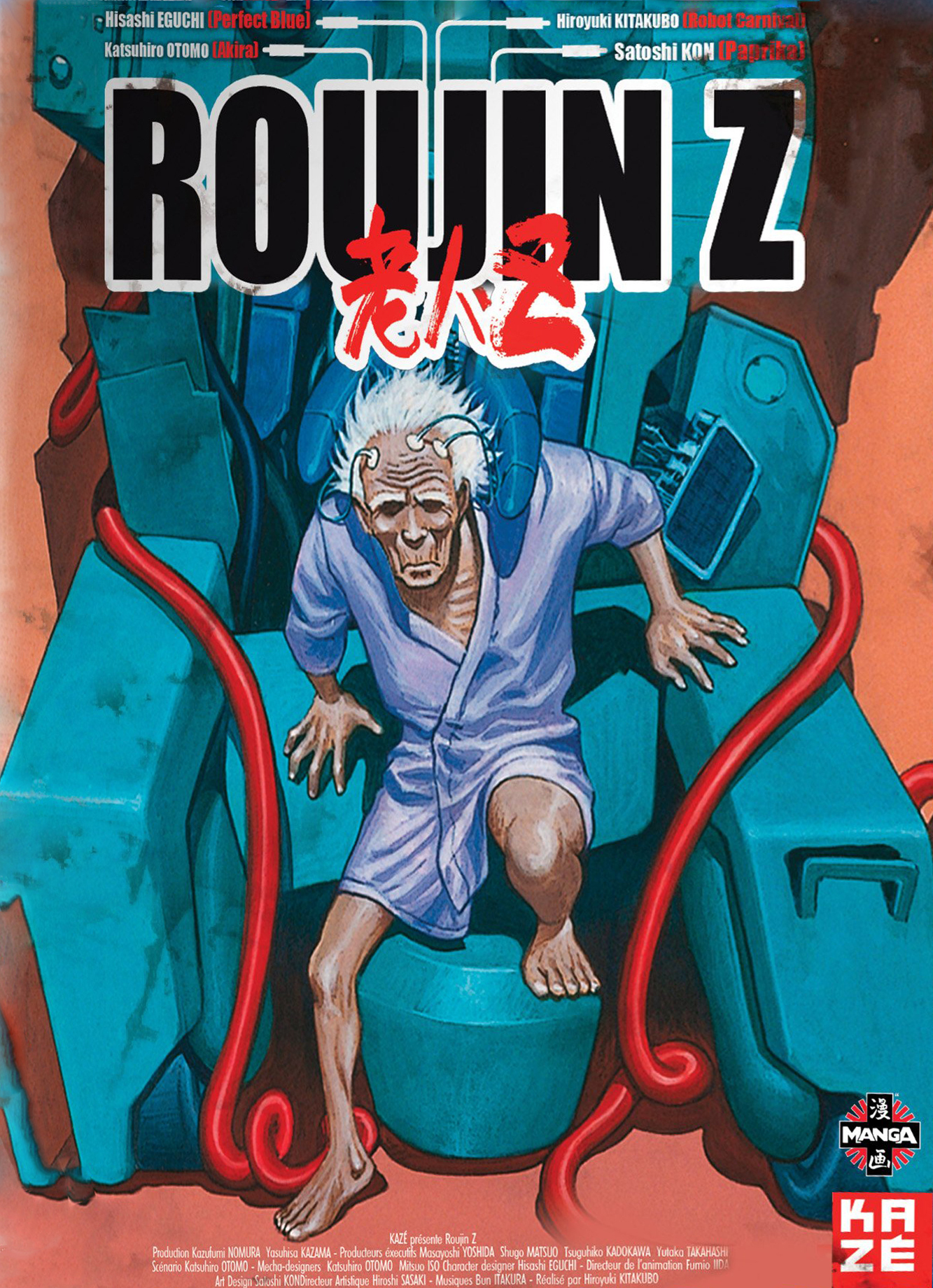

A film like “Roujin-Z” shows how animation can liberate filmmakers to deal with themes that would be impossible in a conventional movie. It was written by the major anime figure Katsuhiro Otomo, whose “Akira” (1990) was an animated vision of a nightmare future urban world. His new film is a quite different, but equally savage, satire about healthcare for the aged in the 21st century.

As the story opens, scientists are alarmed that there are too many old people.

Ambitious medical students resent them, because geriatric care is seen as a career dead-end. A computerized machine, named the “Z-001,” is invented to provide a permanent home for the elderly. It’s a walking, talking combination of a hospital bed, a robot and a computer, and once a patient is installed in one, he’s expected to stay there until he dies.

This is quite a machine. It bathes its occupants, massages them, shows them movies and video games, attends to their bathroom functions, diagnoses their ills, and administers medicine. It’s powered by an atomic reactor, and even has a built-in safety device: Should its onboard reactor fail, the machine is programmed to instantly bury itself in concrete. What then happens to the patient? I guess they go down with their ships.

Most everybody likes the Z-001, except for a few humanistic types like a young nurse who feels sympathy for the old man who is berthed in one of the prototypes. Japanese folklore teaches that there can be spirits in almost anything, and in the case of this machine, the computer seems to have been inhabited by the spirit of the old man’s dead wife, who wants to visit the sea. So, the powerful machine makes an effort to break out of the hospital and visit the seaside, with catastrophic results.

I cannot imagine this story being told in a conventional movie. Not only would the machine be impossibly expensive and complex to create with special effects, but the social criticism would be immediately blue-penciled by Hollywood executives. Health care for the aged may be big on Capitol Hill, but it doesn’t sell movie tickets. What’s interesting, as you watch “Roujin-Z,” is how quickly the story itself becomes as interesting as the fact that the movie is animated. Perhaps because of our training with Disney movies, we accept cartoon characters as “real,” and these characters–especially the hapless old man–have a curiously convincing quality.

The dialogue is also intriguing. Dubbed into English, it ranges from standard comic book slang to the thoughtful, literate and controversial. Speech of this level would be dumbed down in a studio rewrite.

The animation, however, is not technically sophisticated by Hollywood standards; the filmmakers are economical with their animation of backgrounds and secondary characters. But here again, there is a gain as well as a loss: They break the film down into storyboarded shots as a comic book might, using unexpected angles and perspectives, shadows and light, surrealism and visual invention, so that the animation, while not as “realistic” as in, say, “Pocahontas,” feels rich and complex.

I am not sure “Roujin-Z” is the film to start with if you’re curious about animation. It’s more for devotees. My recommendation would be “Akira”–or, for family viewing, the delightful “My Neighbor Totoro,” which, like “Babe,” might actually appeal more to adults than children.