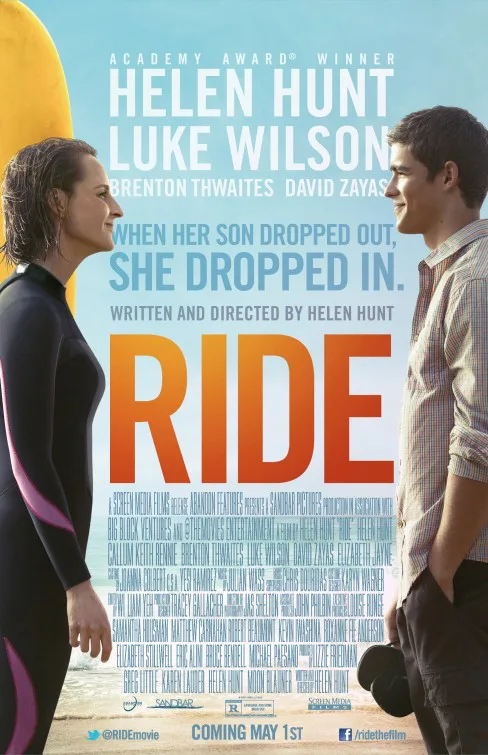

Helen Hunt’s second film as a director, “Ride,” is about a brittle book editor who heals old wounds and her strained relationship with her son by learning to surf. From its opening scenes, it settles into what seems like a familiar if very specific comic mode exemplified by such filmmakers as Woody Allen, Nancy Meyers (“Something's Gotta Give“) and James L. Brooks (“Broadcast News” and “As Good as it Gets,” for which Hunt won an Oscar). The characters in these movies tend to be white, American, upper-middle class to rich, educated, and nervously talkative, and the whole thing tends to be pitched somewhere between a TV sitcom and a laid-back American indie film in which nothing too terribly upsetting happens onscreen. Lessons are learned, loves lost or found, quotable lines uttered, roll credits. None of which is meant to denigrate the movies as unworthy: well-done, they can be incredibly satisfying, and it’s questionable whether they’re any more or less trivial than a superhero film or “Godzilla” in the greater scheme (at least you get to see a version of the actual world on a movie screen). Just that usually you go in having a pretty good idea what you’re in for, and you’re rarely proven wrong.

“Ride,” though, is a somewhat different animal. Hunt, who directs her own original screenplay, nails the Allen-Meyers-Brooks aspect of the film from the opening scene, in which her heroine Jackie banters with her college-bound son Angelo (Brenton Thwaites) about a short story he’s written. The rat-a-tat rhythm of the dialogue, complete with people talking over and past each other, is highly structured, every word and pause carefully chosen to put across a particular rhythmic or emotional effect. Nobody’s just winging it here. The rest of the setup for the story is similarly meticulous, with dialogue scenes and bits of physical comedy blocked as meticulously as anything you might see in a Broadway play (one of the cleverest is the scene where Angelo allays his mom’s fears that he’s moving too far away from her by walking her across the park, counting each step along the way). We deduce that this is a movie about learning to let go, with an empty nest story at its center, and we figure it’ll manifest itself by showing us that Jackie is a control freak, like a lot of older rom-com heroines, and that her son chafes at that even though he obviously has a touch of it himself, and that they’re both going to have to get used to the idea of not being in each other’s lives 24/7.

But then Angelo goes to Venice, California to visit his father and his new family one last time before college and impulsively decides to drop out and just hang around the beach. Suddenly the whole temperament of the film changes, and you start to figure out that the tight-knit relationship between a single mother and her only son is not the main story here, but a gateway into the real main story. Suffice to say that once “Ride” gets around to explaining why Jackie and Angelo are so incredibly, perhaps unhealthily close (bickering and swapping in-jokes like a brother and sister, or an old married couple) and then has Jackie decide to stay in Venice for a while and learn to surf and open some long-locked doors in her psyche, the film goes darker than you expected it to go; but it explores that darkness with a plainspokeness that goes up to the edge of agonized psychodrama but somehow never punctures that feeling that Hunt established early on. This is a remarkable feat that required keen instincts to pull off. It’s as if somebody had spliced bits of a French art house drama about grief, suffering and repression into “Spanglish” or “It's Complicated,” without one aspect canceling out the other.

The film is high-strung, nervous and slightly chilly in the New York scenes, but once the action shifts to the beaches of Venice, it slows down considerably, and fittingly; the rhythm of the waves dictates the pace and color of the movie, and it makes sense to apply the brakes to a story about a woman who’s always talking and working and running all over the place and defining and ranking and describing everything in her life. (Complaining about LA, she says, “By the time you drive to a museum, you’ve lost the will to look at a painting, so it’s hardly a decision based on culture”).

The slowing-down effect of Venice makes it possible for Jackie to actually live in reality rather than hurrying through it or avoiding it. This in turn encourages her to confront the real reason she’s so controlling towards Angelo and so incapable of letting him go. Without giving away the movie’s big reveal (it’s horrifying, in an everyday sort of way, but not “surprising” in a movie way) I can say that once we face it along with Jackie and Angelo and their loved ones, the film seems to go through much the same revelatory experience that Jackie has on the beach as she learns how to ride a board with help from a handsome, slightly younger instructor and soon-to-be-love-interest named Ian (Luke Wilson). It chills out and loosens up. And then it goes deep—deeper than you expected—into pain. There’s a long, wordless sequence out in the ocean, just Hunt on a surfboard, that has the ritualistic power of a sacrament.

“Ride” isn’t going to win any prizes for cinematic innovation. Its comfort in privilege has an irritatingly unexamined quality (Jackie’s got the sort of job where she can fly cross-country for several days and drive to and from the beach in a limo and not be fired immediately). And there are aspects that feel more generous than dramatically wise, such as most of the scenes involving Angelo in LA; I think it would’ve been all right to let him be a supporting character after the film leaves New York and slip toward the margins of the story, which is mainly Jackie’s. Still, this is an unusual movie, especially when you look back and realize how usual it seemed going in.

Certain actors seem to understand their screen persona better than almost any director they’ve worked with. Hunt might be one of them. She’s often been cast as a killjoy, a micro-manager, a voice of reason, or a somewhat abstract figure of mystery and longing, and she’s written a part for herself that incorporates all of those shards. (“It sounds like hubris, but I know that once I get out there I am going to be better than average at intuiting how to do this,” she says, explaining why she doesn’t want surfing lessons at first.) But there’s an earthier, warmer figure buried just beneath Jackie’s surface, and the movie digs her out in a disarmingly natural way. Jackie can get high and laugh endlessly at a completely innocuous question, or march into her ex-husband’s house and have a tearful meltdown that’s been a long time coming while being keenly aware of how inappropriate and selfish it is, to the point of preemptively describing what she thinks the other characters in the room are thinking and feeling about her.

The movie is funny until suddenly it’s not funny at all. Then it’s funny again while discussing the fact that some things really aren’t funny. And near the end, it’s affecting without seeming to try to hard to be affecting. A lot of this has to do with the way Hunt invests ordinary words with strong emotion by having the characters deliver them in an offhand way. “Life is long,” Ian tells Jackie. “It is,” she replies. I hope a lot of people see this movie. It’s not great, but it has greatness in it, and as a filmmaker, Hunt is the real deal.