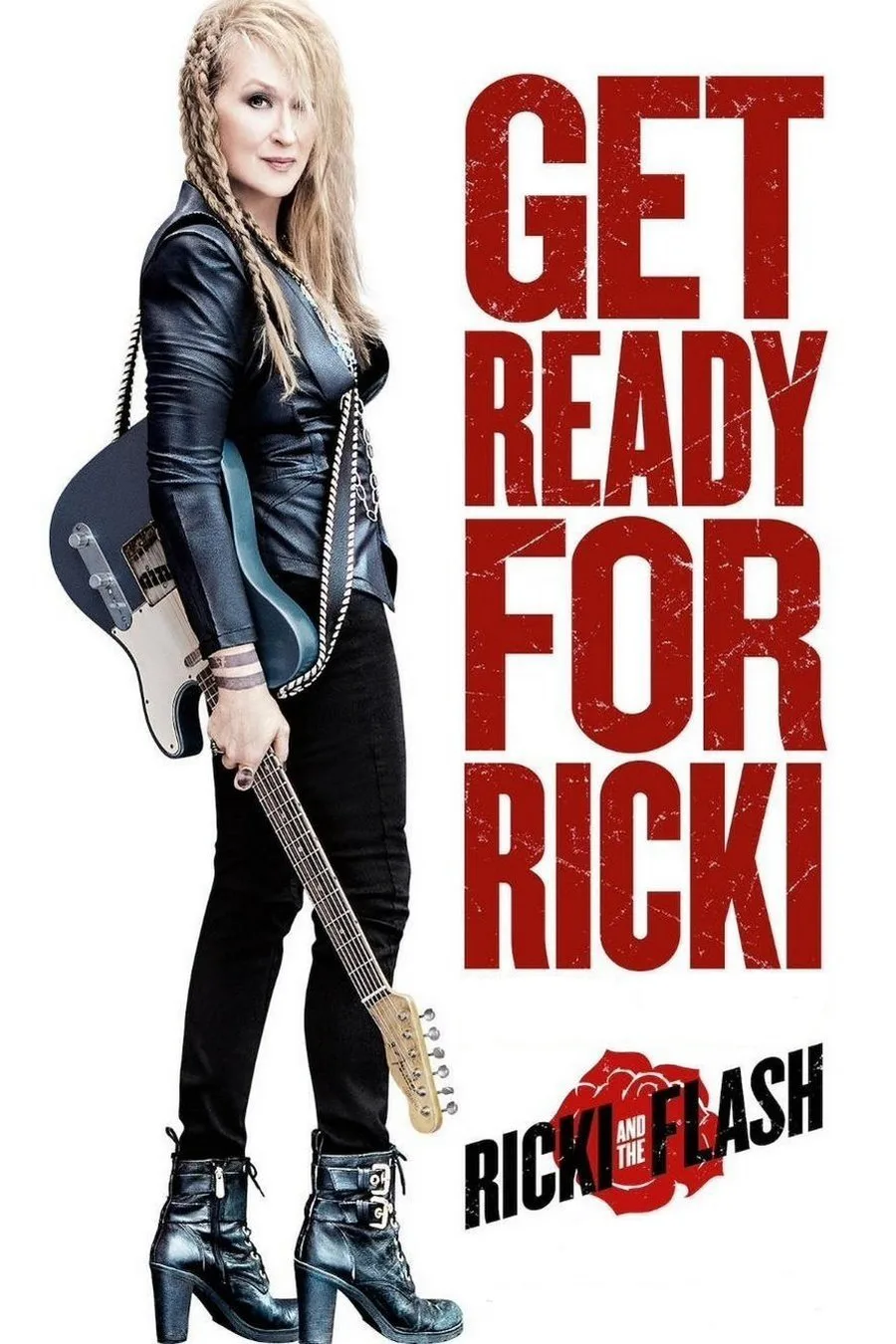

“Ricki and the Flash” is a classic, and classically lamentable, good-news/bad news proposition. In the good news department, it’s largely a sturdy, enjoyable domestic comedy drama. It showcases the sort of typically amazingly diverse and eclectic cast only its director Jonathan Demme can and would put together. When’s the last time you saw a movie that featured both “The Facts of Life” mother-figure Charlotte Rae AND Parliament/Funkadelic keyboard legend Bernie Worrell? That’s right, never. Then there’s the what-can’t-she-do Meryl Streep credibly handling a Fender Telecaster and singing classic rock tunes. A script by Diablo Cody that’s typically acute on the Problems Of Quirky Contemporary Women front and refreshingly low on the ostentatious gratuitous pop culture references. And so on.

The bad news is tougher to detail in good conscience as a spoiler-aware reviewer. The movie, not nearly as treacly a proposition as its trailers suggest, opens with Streep’s Ricki leading her band through Tom Petty’s “American Girl.” If these guys rock a little harder and tighter than your above-average bar band, it’s because they damn well should. Lead guitarist and some-time Ricki romantic interest Greg is Rick Springfield, a chart-topping dude back in the day as well as an actor; bassist is the late Rick Rosas, longtime compatriot of Neil Young and others; the drummer is Joe Vitale, who came up with the Michael Stanley Band. On organ is the aforementioned Mr. Worrell. These vets, even onetime teen idol Springfield, are all relatively grizzled looking, but they’re making the smallish clientele of a Tarzana bar pretty happy. The next day it’s back to real life for frontwoman Ricki: a checkout lane at a Total Foods outlet, a fictionalized version of a very organic chain with high Awful Bourgeois Appeal. Then there’s the phone call from the past. There’s always a phone call from the past. In this case, it’s from a past standing on a manicured lawn in the back of a McMansion in a cul de sac and calling Ricki “Linda” (her given name).

Kevin Kline’s Pete is the ex-husband Ricki left in the lurch after bearing him three children and failing at domestic goddesshood. But it’s quite a lurch he’s made for himself. Still ensconced in Indiana, he has a challenging but very lucrative professional life, a beautiful and sane second wife Maureen (Audra MacDonald) and is still an involved dad to this three adult kids. The oldest of which, Julie (Mamie Gummer, Streep’s real-life daughter) is having a profound crisis after the breakup of her marriage. Absentee mom Ricki/Linda, who hasn’t boarded a jet since well before the creation of the TSA, does her duty and is greeted with surly resentment and seething hatred by Julie. Except Ricki also works some transformational magic on her daughter, routing her rage into a pleasure principle that involves getting pricey manicures on Julie’s soon-to-be-ex-husband’s dime. Ricki’s other kids are a little less ambivalent about her sudden presence; it comes out that the youngest hadn’t even intended to invite her to his wedding. And once Maureen returns from visiting her own family, she’s not too excited that Ricki’s around either.

So far, so okay. One of the nicer things about the movie is how it avoids overt clichés while still partaking of convention. One night in the giant kitchen Ricki asks buttoned-down Pete why he’s got some pot in the freezer; he said it was bootleg-prescribed by a coworker for his migraines. The way for a WACKY pot-smoking scene is clear, but Demme and Cody don’t give us that. They don’t even show Ricki, Pete, and Julie lighting up. Rather, the movie shows them in a semi-stoned family glow a little afterward, the heretofore manic Julie finally getting some rest, Ricki singing one of her own tunes, and Pete grappling with his own clearly very tortured feelings about his past and the woman he’s now got staying in his house. It’s good stuff (and of course it’s beautifully depicted by the uniformly great actors), reminiscent of the quirky moments of grace peppered into a lot of Demme works, ranging as wide as “Melvin And Howard,” “Something Wild,” and “Married To The Mob.”

Now for the bad news. There’s a bit in the movie’s final scene in which Springfield’s character rises from a table and announces “We better get out of here.” My advice to you—and it is very impractical advice because who wants to pay to see a movie and do this?—is that you get up and walk out of “Ricki And The Flash” right then and there. Because what happens next pretty much sells all the good honest work everyone involved has done up to this point down the river, in a conclusion that hard-sells a feel-good cliché with such forced-grin inanity that it feels like a hallucination. “Music is the healing power of the universe,” Albert Ayler said. I kind of believe him. I reckon that Demme believes him too. But not the way it’s depicted here. Here it’s more like “Music is the healing power of the I’m hiding under my couch out of embarrassment for myself and everyone involved.”