The fourth wife of the rich old man comes to live in his house against her will. She has been educated, and thinks herself ready for the wider world, but her mother betrays her, selling her as a concubine, and soon her world is no larger than the millionaire’s vast house. Its living quarters are arrayed on either side of a courtyard. There is an apartment for each of the wives. She is quietly informed of the way things work here. A red lantern is raised each night outside the quarters of the wife who will be honored by a visit from the master.

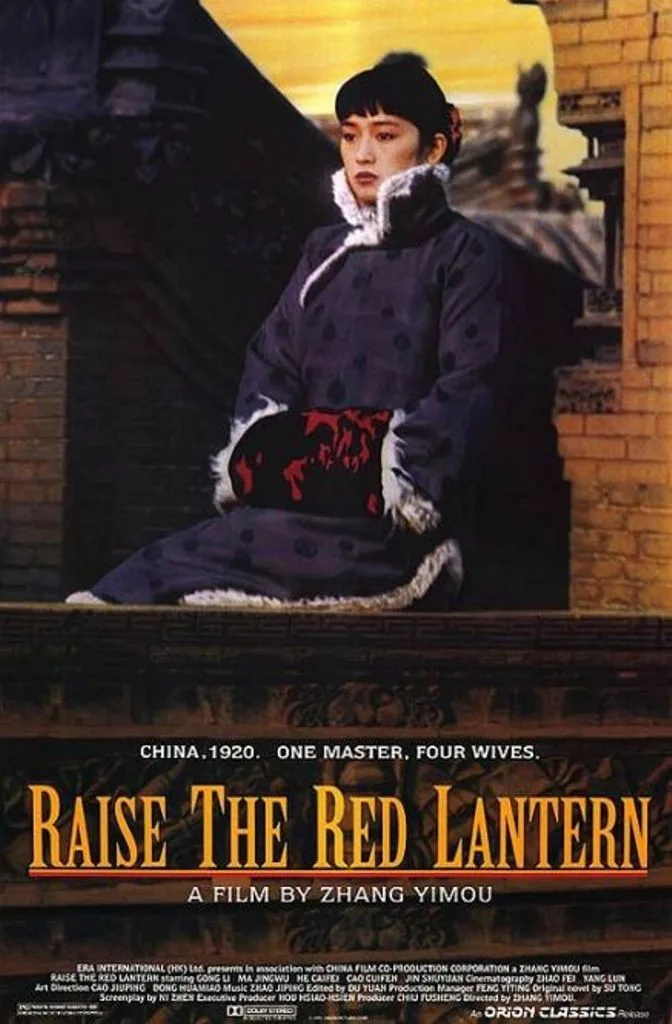

So opens “Raise the Red Lantern,” a Chinese film of voluptuous physical beauty and angry passions. It is one of this year’s Academy Award nominees in the foreign film category, directed by Zhang Yimou, whose “Ju Dou” was nominated last year. This film, based on the novel Wives and Concubines by Su Tong, can no doubt be interpreted in a number of ways – as a cry against the subjection of women in China, as an attack on feudal attitudes, as a formal exercise in storytelling – and yet it works because it is so fascinating simply on the level of melodrama.

We enter into the sealed world of the rich man’s house, and see how jealousies fester in its hothouse atmosphere. Each of the four wives is treated with the greatest luxury, pampered with food and care, servants and massages, but they are like horses in a great racing stable, cared for at the whim of the master. The new wife, whose name is Songlian, is at first furious at her fate. Then she begins to learn the routine of the house, and is drawn into its intrigues and alliances. If you are only given one game to play, it is human nature to try to win it.

Songlian is played by Gong Li, an elegant woman who also starred in quite different roles in Zhang Yimou’s two previous films.

In “Red Sorghum,” she was the defiant young woman, sold into marriage to a wealthy vintner, who takes over his winery after his death and makes it prosperous with the help of a sturdy peasant who earlier saved her from rape. In “Ju Dou,” she was the young bride of a wealthy old textile merchant, who enslaved both her and his poor young nephew – with the result that she and the nephew fall in love, and the merchant comes to a colorful end in a vat of his own dyes.

Zhang Yimou is obviously attracted to the theme of the rich, impotent old man and the young wife. But in “Raise the Red Lantern,” it is the system of concubinage that he focuses on. The rich man is nowhere to be seen, except in hints and shadows. He is a patriarchal offstage presence, as his four wives and the household staff scheme among themselves for his favor.

We meet the serene first wife, who reigns over the other wives and has the wisdom of longest experience in this house. Then there are the resigned second wife, and the competitive third wife, who is furious that the master has taken a bride younger and prettier than herself. The servants, including the young woman assigned to Songlian, have their own priorities. And there is Dr. Gao (Zhihgang Cui), who treats the wives, and whose medical judgments are instrumental in the politics of the house. The gossip that whirls among the wives and their servants creates the world for these people; little that happens outside ever leaks in.

Zhang Yimou’s visual world here is part of the story. His master shot, which is returns to again and again, looks down the central space of the house, which is open to the sky, with the houses of the wives arrayed on either side, and the vast house of the master at the end. As the seasons pass, the courtyard is sprinkled with snow, or dripping with rain, or bathed in hot, still sunlight. The servants come and go. Up on the roof of the house is a little shed which is sometimes whispered about. It has something to do with an earlier wife, who did not adjust well.

Yimou uses the bold, bright colors of “Ju Dou” again this time; his film was shot in the classic three-strip Technicolor process, now abandoned by Hollywood, which allows a richness of reds and yellows no longer possible in American films. There is a sense in which “Raise the Red Lantern” exists solely for the eyes. Entirely apart from the plot, there is the sensuous pleasure of the architecture, the fabrics, the color contrasts, the faces of the actresses. But beneath the beauty is the cruel reality of this life, just as beneath the comfort of the rich man’s house is the sin of slavery.