Sex, it is said, is the only luxury with which the poor are as well supplied as the rich. But within the rigid Chinese feudal society depicted by “Ju Dou,” that is not quite the case. The movie, which is set in the 1920s but might as well be set a century earlier, tells the story of a wealthy old textile man who marries a juicy young bride and hires a desperate young nephew and enslaves both of them with his cruel will.

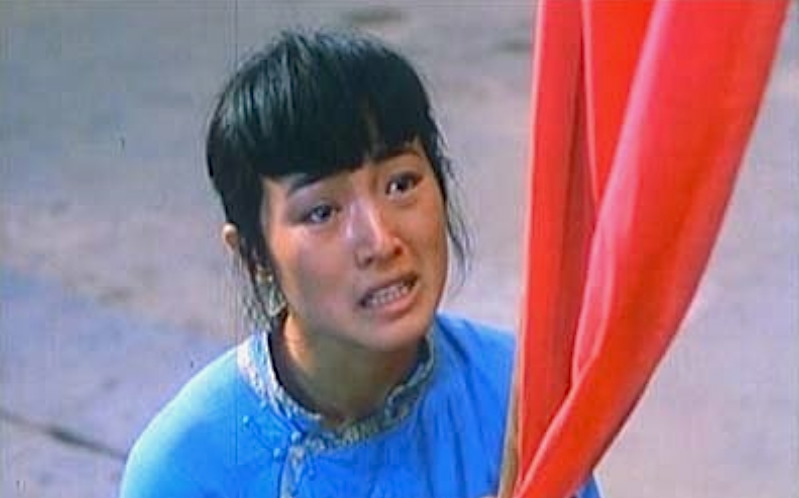

The old man owns a factory where he dips bolts of cloth in great vats of bright dyes, and then hangs them on long poles to dry. The cloth is bold and brilliant, the colors of passion, but nothing to compare to the emotional tumult taking place beneath the old villain’s roof. He is sadistic and impotent, and entertains himself by tormenting his bride while the nephew listens in the middle of the night. The nephew is too poor, of course, to afford a wife, and the bride too poor to take the husband of her choice. But one day she deliberately reveals herself to the young man, he is easily seduced, and they have a child who she convinces the old man is his own.

The infant grows into a hateful, strong-willed little monster, while the old man grows older and eventually cripples himself in an accident. He has a cart built, in which he pushes himself around his domain, while the nephew and wife continue their affair. Their deception becomes even more dangerous when the child grows old enough to understand what is going on; ironically, he resembles the sour merchant more than the lusty young man who fathered him.

The ending of “Ju Dou” is as lurid and melodramatic as anything conceived by Poe or filmed by Bunuel, and it exhibits justice completely untempered by mercy. But long before the gory finale, the Chinese censors had apparently already decided to suppress this film, which was directed by a young turk named Zhang Yimou. The film was suppressed in China, but went on the international festival circuit, and won a best director award at Cannes and the Golden Hugo at Chicago before becoming one of this year’s Oscar nominees in the foreign language category, over the official objections of the Chinese.

Why did the Chinese film establishment find “Ju Dou” so offensive? It is tempting for us to read it as a political parable, to see the old merchant as an example of the old order of Maoism, and the hateful boy as a symbol of the Red Guard. But the Chinese might just as easily have been offended by the sexuality, which is frank for a Chinese film and for a puritanical society.

The film appealed to me for two reasons. First, because of its unabashed, lurid melodrama, in which the days are filled with scheming and the nights with passion and violence. Second, because of its visual beauty. When the Technicolor company abandoned its classic three-strip process for reproducing color on film, two of its factories were closed down but the third was packed up and sold to China, and that is why the bright colors in the vats of the textile mill will remind you of a brilliance not seen in Hollywood films since the golden age of the MGM musicals. Not that this story would have been very easily set to music.