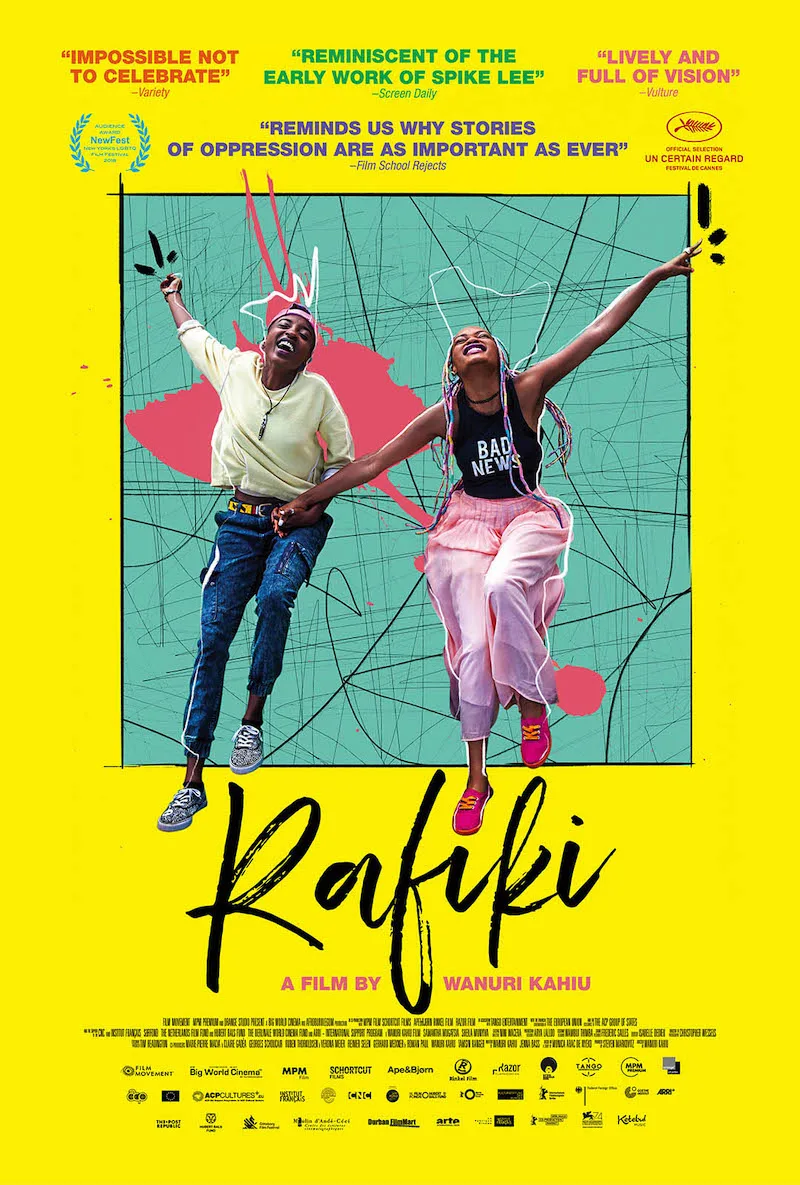

“Rafiki” is a lesbian romance set in a place where such love stories, in real life and onscreen, are forbidden by law. It is the first Kenyan film to be screened at Cannes and, more importantly, the first film with a positive message about homosexuality to play in Kenyan theaters. The latter occurred after a successful Supreme Court defeat of a ban imposed by the government. In the ruling, the judge wrote, “I am not convinced that Kenya is such a weak society whose moral foundation will be shaken by watching a film depicting a gay theme.” And yet, morality is a commonly used excuse wielded like a cudgel against civil rights at worst, mere representation at best. Why is the act of being seen in a positive light such a “moral” threat?

Director Wanuri Kahiu creates a lyrical ode to finding a kindred spirit amidst an uncaring majority by using Monica Arac de Nyeko’s short story, “Jambula Tree” as her basis. The cinematography is as lively, colorful and engaging as the hairstyle of Ziki Okemi (Sheila Munyiva), the boisterous object of affection for our protagonist, Kena Mwaura (Samantha Mugatsia). Several times, lens flares from the Sun invade the frame containing Ziki, presenting her as the center of Kena’s galaxy. Ziki’s astonishingly festive coif becomes a complementary personality symbol, the yin to the grungy yang of Kena’s skateboard and backwards baseball cap; Kahiu often introduces these characters into scenes by their trademarks.

<span class="s1" The way Kena dares to publicly gaze at Ziki reveals a mixture of the naïveté in handling a first love and a teenager’s penchant for defiance. Ziki returns the gaze even more forcefully, which scares Kena. Their feelings are not tolerated by society, and while their story has a simplicity that feels at times a bit too light, Kahiu never shies away from the inherent danger the lovers face. When violence befalls Ziki and Kena, Kahiu’s tight framing is as harrowing as the act itself. The canvas of the screen is often used as a representation of feeling rather than narrative, with scenes cropped so we can only see pieces of the action. It makes the most intimate moments seem larger-than-life, which is exactly how they must feel to our heroes.

Ziki and Kena are the daughters of rival politicians, which adds an extra layer of problems to their relationship. Gossips like storefront owner Mama Atim (Muthoni Gathecha) can’t wait to wag their tongues about the burgeoning friendship between the progeny of political enemies. There’s also a class difference. Kena’s dad, John (Jimmy Gathu) runs a store while the more financially successful Okemis are, in the words of Kena’s mother, “folks who can elevate you.” These issues would be enough strife for most cinematic lovers, but there’s also the patriarchal ideas perpetuated by Nairobi society. “Good Kenyan girls make good Kenyan wives,” we’re told. The men we meet like Blacksta (Neville Misati) flaunt the one-sided rules of romantic entanglement, peppering any and every woman with raunchy come-ons. They also torture the one man they consider to be gay, yelling homophobic slurs at him as he quietly walks through the neighborhood.

This nameless man—the film never reveals whether he is gay or just perceived as such—becomes a rather blatant symbol of the country’s homophobia. He never gets a line of dialogue, which bothered me initially because I saw his existence as an empty gesture. But, late in the film, Kahiu upended my expectations in a scene where he quietly sits next to a battered, heartbroken Kena. As the two share the frame, neither making eye contact with the other, I hoped for some exchanged words. Instead, the scene ends in silence and I realized that the visual of a shared solidarity was more powerful than anything that could have been said in that moment.

“Rafiki” has several quiet scenes like that, which elevates the familiar material. And unlike older films such as “The Children’s Hour,” this doesn’t end with sacrifice and punishment but with hope and ambiguity. Munyiva and Mugatsia are both excellent, sharing an energetic chemistry that the film can’t help but amplify in its tone. This is a bittersweet yet ultimately positive depiction of young, forbidden love that radiates empathy by showing how misguided it is to be against this kind of devotion. Kahiu draws blood with a “pray away the gay” scene that left me fuming, but she also finds a surprising level of understanding in a few secondary characters.

When the ban was lifted and “Rafiki” got a week’s run in Kenyan theaters, it sold out and even beat “Black Panther” at the box office. I imagine some of that came from a morbid “how bad could it be to have been banned?” curiosity, but I’ll bet most of the audience was driven to it simply to feel the joy of seeing themselves warmly represented onscreen. To feel seen is a potent, potentially life-changing emotion, and only those who were never in the dark would have a moral problem with it. “Rafiki” makes this serious point quite effectively, never losing its ebullience.