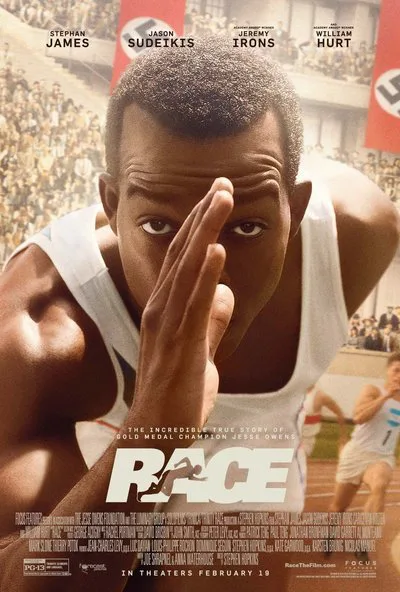

“Race” takes a complicated, messy story and shapes it with the bland cookie-cutter mold too often seen in the biopic genre. The predictability of its storytelling beats isn’t really the problem, for there is comfort to be found in the dance of the familiar. The issue here is the tone of the material. Writers Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse coddle the viewer, never once hitting us with the full brunt of the current and future horrors experienced by Blacks in America and the Jews in Germany during this period. It’s as if an undiluted moment of true discomfort or complexity would destroy rather than amplify the uplifting moments. Additionally, the film’s subject, Jesse Owens, has to share his tale with someone who deserves to be the subject of her own movie. While the ads hype Owens’ heroism, they don’t tell you that “Race” sees propaganda filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl as an equally big hero. This may work for cinephiles, but it left a sour aftertaste for me.

Owens’ story is a fascinating tale of record-breaking athleticism enacted in a time of racism and anti-Semitism. Shady, controversial dealings stopped an Olympic boycott and enabled the United States to compete in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The games were presented by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels as proof of Aryan superiority, yet their athletic German engineering was no match for a man deemed inferior to Whites by the United States and Nazi Germany. Owens (a fine Stephan James from “Selma”) chose to defy a boycott-favoring consensus that included the NAACP in order to live his dream of Olympic glory, yet when he returned with four gold medals, his heroics were no match for the racist status quo. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wouldn’t congratulate nor meet with him, and Owens couldn’t use the front door of the Waldorf-Astoria to attend a dinner held in his honor.

To its credit, “Race” ably covers all this material. But this is an easily distracted movie. For example, there’s an interminable subplot involving Owens’ dalliance with a woman who was not his high school sweetheart/eventual wife Ruth (Shanice Banton). It goes nowhere except to the land of cliché, serving as a means to inject conflict into the Owens’ relationship. More time is spent on Riefenstahl interacting with people than Owens bonding with his teammates or training. Despite an admirable attempt by Banton and James to bring a sense of romance to their underwritten scenes, and James’ enjoyable interactions with a surprisingly good Jason Sudekis as Coach Larry Snyder, it often feels as if Jesse Owens is trotted out simply to win the races that made him famous.

The solid cast is rounded out with veteran actors including Jeremy Irons and William Hurt, both of whom elevate the material. Irons, as Avery Brundage, is especially good here; he brings a Trump-like essence to all the showy, non-athletic scenes. Whether he’s arguing with Hurt’s Jeremiah Mahoney or negotiating with Barnaby Metschurat’s Goebbels for an appearances-sake only moratorium on the harsh treatment of Jewish people, Irons is a commanding presence even if you know the film is downplaying some of the more sinister aspects of his storyline.

Director Stephen Hopkins shoots the film, and the big races, with minimal fuss or theatrics, but he does have one superbly showy moment when Owens first enters the Olympics stadium. The tricky camerawork, the CGI crowd and James’ awed reaction work together to present a “you are there” moment that’s truly captivating. James is also quite convincing in Owens’ heats, running in the same manner Owens would have back in 1936. The best scenes in the film occur in this section, when Owens meets Carl “Luz” Long (David Kross), a German rival who later becomes a very good friend. Long’s admiration for the man he hoped to beat led him to violate several unspoken rules of the games, including celebrating with Owens after he breaks the long jump record. These scenes highlight what “Race” could have been had it focused more on Owens’ personal relationships.

Since there has only been one other telling of Owens’ story (the 1984 TV movie starring Dorian Harewood and Debbi Morgan) “Race” is to be commended for bringing a new generation to this American hero. I can see it being shown in high schools as a teaching tool and to track teams like the one I once ran on in my youth. But I’m giving the film a marginally negative grade for three reasons, none of which should prohibit you from seeing “Race” if you so desire.

First, the Leni Riefenstahl scenes are completely out of place. It’s not that she shouldn’t have been in the movie—after all, her “Olympia” (which I’ve seen and is quite interesting) captured the footage of Owens to which we otherwise would never have borne witness—nor is it because of Carice Van Houten’s (“Black Book”) performance (she’s good). It’s out of place because “Race” doesn’t acknowledge why Riefenstahl was there in the first place: to document the supposed superiority of the White race. She got lucky, from a filmmaking perspective, when Owens showed up to kick ass, but she had no idea he’d cause that much of a stir. “Race” instead presents her as a Hitler-defying subversive, standing up to Goebbels in a scene I simply did not buy. Riefenstahl deserves her own movie, and should have been on the sidelines of this one.

Second, this material needed a little more edge and darkness. Hopkins can’t even let the powerful scene of the Owens’ entering the side entrance of the Waldorf affect and leave us with sadness and anger. The film interrupts it with a staged moment of hope, as If to say “see, it wasn’t all that bad!” It was that bad.

Third, “Race” is very good at showing us what Jesse Owens did, but falters at showing us who Jesse Owens was. When the film is over, ask yourself if you thought he was completely fleshed out as a character. That may not bug you as much as it did me, so I won’t begrudge you if “Race” makes you stand up and cheer with impunity.