Auteurship, to paraphrase a familiar ad, has its privileges. In the standard Hollywood way of making movies, stories designed to galvanize millions (often derived from books or comic strips that have already done so) and stars that can “open” films are what get productions funded. In Europe, traditional home of the auteur, however, things are somewhat different: A movie like John Boorman’s “Queen and Country”—with no stars and a story based on the filmmaker’s own life—can attract financing because the auteur’s distinctive gifts are considered sufficient to guarantee it audiences and prestige.

Which is to say that Boorman’s latest is not for folks who’ve never heard of John Boorman. But for cinephiles who’ve followed this 82-year-old British filmmaker’s long and sometimes eccentric career with interest and admiration, “Queen and Country” will be a sure winner. A sequel to the similarly autobiographical “Hope and Glory,” one of Boorman’s most renowned films (it received five 1987 Oscar nominations including Picture, Director and Screenplay), the new work is obviously personal yet also entertaining, accessible and beautifully crafted.

It begins with a key comic moment from “Hope and Glory,” when the boy protagonist’s school is destroyed by a German bomb during a 1943 air raid. When the narrative jumps forward nine years, it finds Bill Rohan (Callum Turner), now 18, and his family still living at the home on a Thames island where they went to escape the Blitz. It is a lovely, idyllic place, and slightly surreal since moviemakers from nearby Shepperton Studios pop up to shoot scenes unexpectedly. But the idyll is not to last. Bill receives a notice to report for his two years of compulsory military service.

The first word in the film’s title says lots about the precise historical moment Boorman evokes. When Bill enters the army, Britain has a king. During his stint, Elizabeth II takes the throne, with all the symbolic resonance that entails (Boorman’s English films appreciate the monarchy’s mythic aura). The Korean War is on. Britain is poor, its empire is crumbling, and the Swinging Sixties are still far, far away.

The film’s account of Bill’s military service has an anecdotal air, conveying the daily grind and comic absurdity of life in a drab rural base. Assigned to teach typing to Korea-bound recruits, he starts reading up on the conflict and soon conveys his jaundiced view of the contest between capitalism and communism to his students. The effect this has on morale is not salutary. When one conscript refuses service in Korea citing Bill’s opinion that it’s an “immoral war,” he is charged with “seducing a soldier from the course of his duty” – an indictment containing a verb that’s the source of much merriment and jibing.

Bill’s best friend and fellow typing instructor, a puckish rogue named Percy (Caleb Landry Jones), joins him in a constant low-grade war against their superior officer. Sgt. Major Bradley (David Thewliss), a fanatical stickler for the rules, is so offended by the two young men’s casual irreverence that he misses no opportunity to bring them up on disciplinary charges to his superior, the constantly exasperated Major Cross (Richard E. Grant).

Percy’s major salvo in the battle against his and Bill’s superiors comes after he realizes there’s an antique clock in the officers’ mess that’s a source of regimental pride. One night, he manages to smuggle it out to his and Bill’s room, and later mails it off the base. The furious consternation this causes among the officers hands Percy a mirthful victory that he and Bill relish even as they’re obliged to keep it secret.

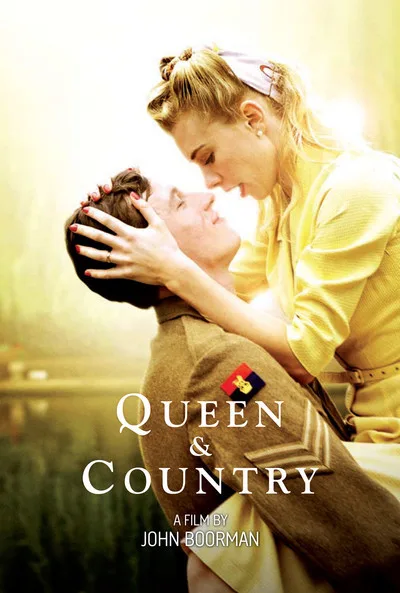

Off-base, the two friends attend concerts in a nearby town where their main objective is seeking out female company. Early on, they meet two nurses who seem equally interested in their companionship. Percy becomes enamored of one who, it turns out, is more interested in Bill. But Bill’s interests are elsewhere. He has spotted a beautiful, elegant blonde (Tamsin Egerton) and he pursues her even after she makes it plain that she’s not available. Since she won’t tell him her name, he dubs her Ophelia.

In the tale’s second half, Bill and Percy get a break from military hassles when they visit Bill’s family on their island. Watching the new queen’s coronation on TV—a brand-new device acquired for the occasion—Bill spots Ophelia among the assembled aristocrats. Percy, meanwhile, becomes preoccupied with Bill’s older sister, Dawn (Vanessa Kirby), who has abandoned her Canadian marriage and returned home with her two kids.

Given its loose-knit narrative, the film doesn’t have anything like a conventional structure. Yet it’s steadily engrossing due to Boorman’s surpassing skills as both a storyteller and a director. Indeed, “Queen and Country” could serve as a master class on how to build interesting characters in even the smallest roles, and how to stage scenes with a maximum of expressiveness, elegance and economy. There’s nothing showy about Boorman’s style. Compared to “Point Blank,” “Excalibur,” “Zardoz” and other of his films, its manner is faultlessly understated – the mark of a master with nothing to prove.

As often with Boorman, there are endless pleasures to be found in the film’s performances. Veterans including Thewliss and Grant have a field day with their amusing roles, and young Callum Turner proves a very solid, appealing Bill. But the cast’s standout has to be Caleb Landry Jones, whose Percy is a sparkplug of comic energy and idiosyncrasy. The Texas-born actor ends up accounting for one of the director’s most memorable characters—which, considering this is Boorman, is saying something.