There is sometimes a notion that documentaries should observe events but not influence them. The French term cinema verite (“the cinema of truth”) supposes that the camera is an invisible observer at real events. The audience presumably witnesses what would have really happened even if the camera wasn’t there.

A recent documentary like “Streetwise,” about the street children of Seattle, creates that feeling with scenes so spontaneous we assume the camera must have been hidden, or that the participants were so accustomed to its presence that they forget it was there. Fredric Wiseman’s documentaries on PBS (“High School,” “Basic Training”) give the same impression.

In documentaries like “Pumping Iron II” and the gospel-music film “Say Amen, Somebody,” however, the filmmakers have done their reporting first. They have identified the leading players, isolated the points of conflict and then they set up scenes in which they know more or less what is likely to happen The dialogue is spontaneous, and unexpected events do occur, but within the framework of an over-all story line.

Which kind of documentary is more “real”? Some filmmakers argue that the camera is never invisible and that it’s conceit to claim it is. The word “documentary” itself is misleading, they say. A better term is “nonfiction film.” John Grierson the pioneer British documentarian, provided the best definition of what is really happening when he described a documentary as “a film in which the drama is provided by facts, rather than fiction.”

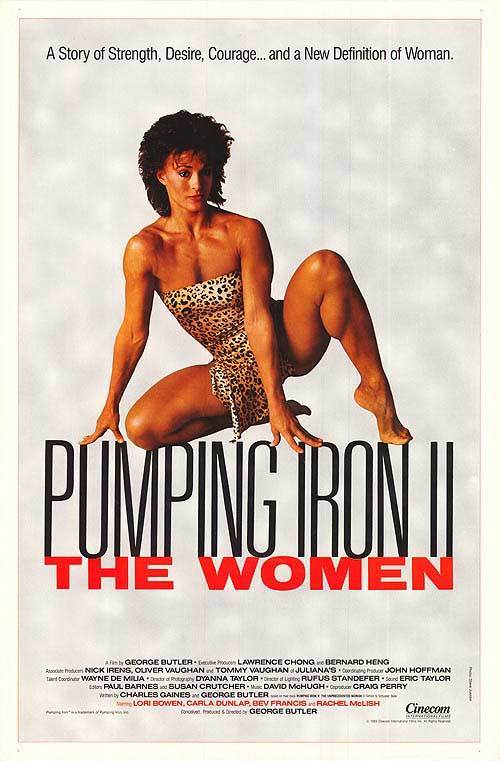

The music is “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” the theme of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” From a concealed staircase at the back of the stage, an awesome human figure emerges. The backlighting makes it hard to discern: Is this Arnold Schwarzenegger? Sylvester Stallone? Not even close. This is Bev Francis, an Australian power-lifter who, is the most muscular woman in the world.

The idea of women with big muscles is still a little strange. Spending some time with the stars of “Pumping Iron II: The Women” at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, I was struck by the reactions they inspired from people on the street, who stopped, turned and stared at these women with broad shoulders and huge biceps. Until the last few years, crowds at Cannes have traditionally been drawn by women with exaggerated feminine physiologies; now here were women from the covers of muscle magazines, and the French, usually so blasé, simply did not know how to react.

At first sight, there is something disturbing about a woman with massive muscles. She is not merely androgynous, a combination of the sexes like an Audrey Hepburn or a Mick Jagger, but more like a man with a woman’s face. We are so trained to equate muscles with men, softness and a slight build with women that it seems nature has made a mistake.

The impulse is to reject muscle-women as freaks, and that is probably going to be the first reaction of the audiences for “Pumping Iron II,” a companion to the original “Pumping Iron,” which made Schwarzenegger a star.

The intriguing thing about the movie is how it alters our original reactions, involving us in the sport of women’s bodybuilding, using the clichés of all sports to make us fans of this one, until by the end of the movie we’re watching the 1983 International Women’s Body-Building Competition with a connoisseur’s eye. If we don’t know how we feel about women with muscles, neither do the judges; the entry of Bev Francis into the competition inspires a philosophical debate about the definition of “femininity.”

Because Francis is by far more muscular than any other women in the competition – including former champions Rachel McLish and Carla Dunlap – she should be the obvious favorite. But some of the judges say she doesn’t look like a woman. Should she? Is this a bodybuilding competition, or a beauty pageant? McLish, with her Farrah Fawcett hairstyle and rhinestone bra, has an obvious cheesecake appeal. Dunlap, Lori Bowen and others in the finals are good-looking women. Francis looks like she belongs on the wrestling team. Her entry forces the judges – a hopelessly inept group – to define their terms.

Meanwhile, we go backstage. George Butler, who has directed both “Pumping Iron” films, makes no pretense that his films are cinema verite. The documentary is scripted, in the sense that scenes are set up to dramatize Butler’s points – even though the subjects and their dialogue are “real.” We see Francis training in Australia, Dunlap talking with her mother, Bowen confessing that she idolizes Rachel McLish and McLish tying bodybuilding into born-again Christianity.

There are the obligatory gymnasium scenes, as the women work out, and the movie makes no secret of the narcissism implied by the sport. The real competition is with, the mirror. The stage competition, at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, is more of a performance. The women line up, pair off for comparisons, are judged singly and in groups, displaying their basic muscle groups. The contest is so frankly obsessed with the details of these physical bodies that it seems like a particularly honest Miss America competition: We all know what we’re here for, and there are no essays to write or songs to sing.

If anything sets the muscle-women apart from the Miss Americas, however, it’s their intelligence. Miss Americas almost always, share a stunning gift for the banal, for rehearsed clichés from civics class. The body-builders are, without exception, articulate about what they are doing, and why. It has taken them, after all, a great deal more effort over a much longer time to get to their championship competition, and they have had to spend much of that time defending the very idea of their sport.

They are also, I thought, more articulate than most other athletes of either sex. Most competitive sports come already packaged with a complete set of rationales and clichés; nobody asks a football player to defend the idea of football, Nobody asks Chris Evert if she thinks playing tennis means she doesn’t really want to be a woman. Body-building is a sport that seems to be about defining muscles, but “Pumping Iron II” shows that it is at least as much about defining attitudes and definition of sexuality. You walk into this movie expecting to see a lot of sweat, and you walk out with more to think about than you bargained for.