“I rob banks,” John Dillinger would sometimes say by way of introduction. It was the simple truth. That was what he did. For the 13 months between the day he escaped from prison and the night he lay dying in an alley, he robbed banks. It was his lifetime. Michael Mann‘s “Public Enemies” accepts that stark fact and refuses any temptation to soften it. Dillinger was not a nice man.

Here is a film that shrugs off the way we depend on myth to sentimentalize our outlaws. There is no interest here about John Dillinger’s childhood, his psychology, his sexuality, his famous charm, his Robin Hood legend. He liked sex, but not as much as robbing banks. “He robbed the bankers but let the customers keep their own money.” But whose money was in the banks? He kids around with reporters and lawmen, but that was business. He doesn’t kid around with the members of his gang. He might have made a very good military leader.

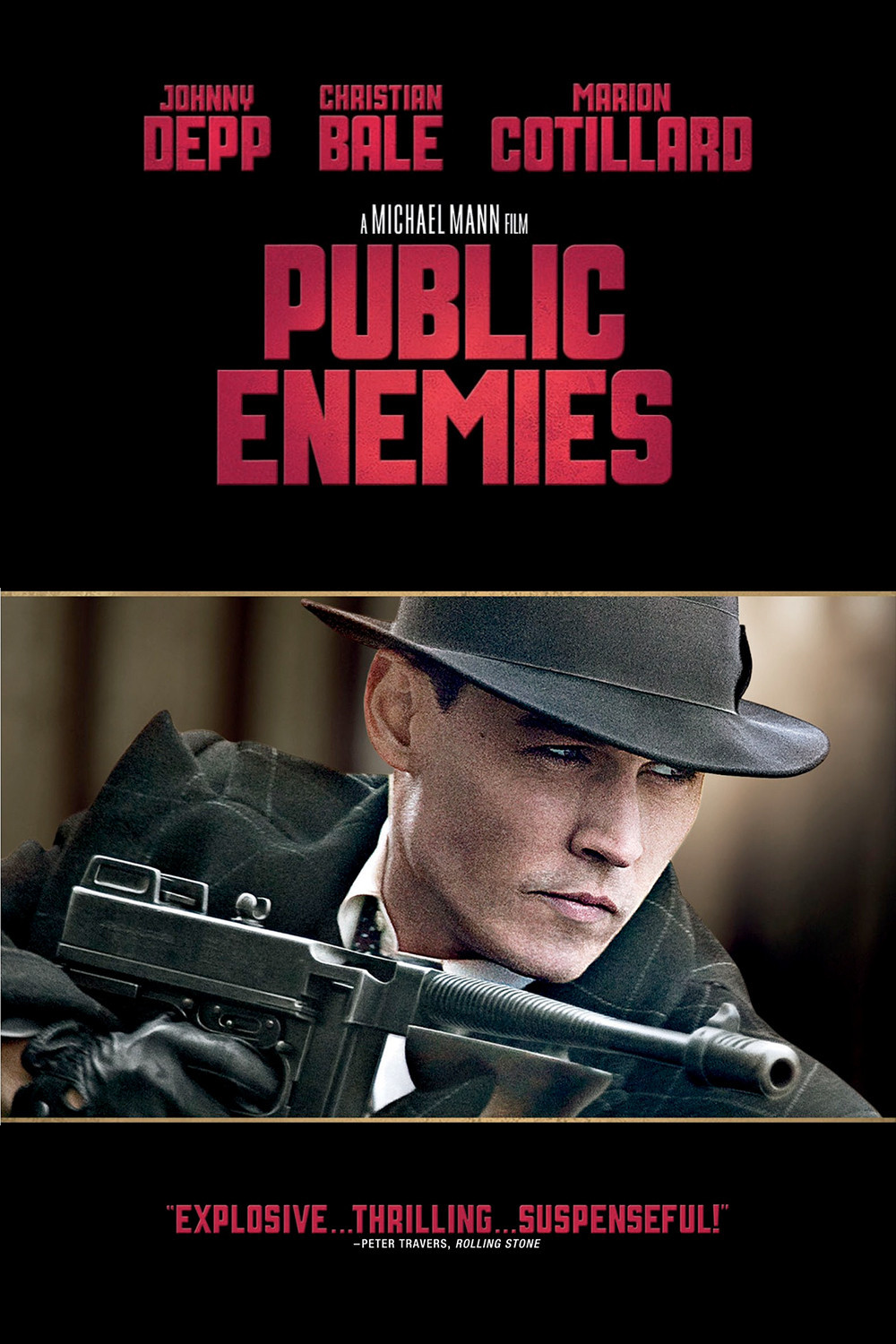

Johnny Depp and Michael Mann show us that we didn’t know all about Dillinger. We only thought we did. Here is an efficient, disciplined, bold, violent man, driven by compulsions the film wisely declines to explain. His gang members loved the money they were making. Dillinger loved planning the next job. He had no exit strategy or retirement plans.

Dillinger saw a woman he liked, Billie Frechette, played by Marion Cotillard, and courted her, after his fashion. That is, he took her out at night and bought her a fur coat, as he had seen done in the movies; he had no real adult experience before prison. They had sex, but the movie is not much interested. It is all about his vow to show up for her, to protect her. Against what? Against the danger of being his girl. He allows himself a tiny smile when he gives her the coat, and it is the only vulnerability he shows in the movie.

This is very disciplined film. You might not think it was possible to make a film about the most famous outlaw of the 1930s without clichés and “star chemistry” and a film class screenplay structure, but Mann does it. He is particular about the way he presents Dillinger and Billie. He sees him and her. Not them. They are never a couple. They are their needs. She needs to be protected, because she is so vulnerable. He needs someone to protect, in order to affirm his invincibility.

Dillinger hates the system, by which he means prisons, that hold people; banks, that hold money, and cops, who stand in his way. He probably hates the government too, but he doesn’t think that big. It is him against them, and the bastards will not, can not, win. There’s an extraordinary sequence, apparently based on fact, where Dillinger walks into the “Dillinger Bureau” of the Chicago Police Department and strolls around. Invincible. This is not ego. It is a spell he casts on himself.

The movie is well-researched, based on the book by Bryan Burrough. It even bothers to try to discover Dillinger’s speaking style. Depp looks a lot like him. Mann shot on location in the Crown Point jail, scene of the famous jailbreak with the fake gun. He shot in the Little Bohemia Lodge in the same room Dillinger used, and Depp is costumed in clothes to match those the bank robber left behind. Mann redressed Lincoln Avenue on either side of the Biograph Theater, and laid streetcar tracks; I live a few blocks away, and walked over to marvel at the detail. I saw more than you will; unlike some directors, he doesn’t indulge in beauty shots to show off the art direction. It’s just there.

This Johnny Depp performance is something else. For once an actor playing a gangster does not seem to base his performance on movies he has seen. He starts cold. He plays Dillinger as a Fact. My friend Jay Robert Nash says 1930s gangsters copied their styles from the way Hollywood depicted them; screenwriters like Ben Hecht taught them how they spoke. Dillinger was a big movie fan; on the last night of his life, he went to see Clark Gable playing a man a lot like him, but he didn’t learn much. No wisecracks, no lingo. Just military precision and an edge of steel.

Christian Bale plays Melvin Purvis in a similar key. He lives to fight criminals. He is a cold realist. He admires his boss, J. Edgar Hoover, but Hoover is a romantic, dreaming of an FBI of clean-cut young accountants in suits and ties who would be a credit to their mothers. After the catastrophe at Little Bohemia (the FBI let Dillinger escape but killed three civilians), Purvis said to hell with it and made J. Edgar import some lawmen from Arizona who had actually been in gunfights.

Mann is fearless with his research. If I mention the Lady in Red, Anna Sage (Branka Katic), who betrayed Dillinger outside the Biograph when the movie was over, how do you picture her? I do too. We are wrong. In real life she was wearing a white blouse and an orange skirt, and she does in the movie. John Ford once said, When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. This may be a case where he was right. Mann might have been wise to decide against the orange and white and just break down and give Anna Sage a red dress.

This is a very good film, with Depp and Bale performances of brutal clarity. I’m trying to understand why it is not quite a great film. I think it may be because it deprives me of some stubborn need for closure. His name was John Dillinger, and he robbed banks. But there had to be more to it than that, right? No, apparently not.