Howard Stern has been accused of a lot of things, but he has never been accused of being dumb. With “Private Parts,” his surprisingly sweet new movie, he makes a canny career move: Here is radio’s bad boy walking the finest of lines between enough and too much.

His fans will find enough of the Howard whose maxims include “lesbians equal ratings.” General audiences will be seduced by the film’s story line, which exploits three time-honored Hollywood formulas: (1) rags to riches, (2) I gotta be me and (3) hey, underneath it all I’m really just a cuddly teddy bear.

The movie shows the coronation of a geek. In grade school, we learn, Howard’s father made a more or less daily practice of calling him a moron.

Howard was the only white kid in an all-black high school. He didn’t date until college (even a blind girl turns him down, after feeling his nose), and he married almost the first woman who was nice to him. Played by Mary McCormack, his wife, Alison, plays a key role in the film, which asks as its underlying subplot, “How much will this woman put up with before she dumps him?” The answer, as Stern listeners know, is “a lot.” “Private Parts” is a biopic about an awkward kid with a bad radio voice and such shaky breath control that he was always running out of steam in the middle of the call letters. Working at a 40-watt station, he’s promoted to program manager because he’s such a lousy DJ, and is told by the station owner: “Disc jockeys are dogs. Your job is to make them fetch.” Fired from a country station he hates, Howard tells Alison: “I have to be myself on the radio and tell the truth. I have to go all the way.” He does. He reveals things about their marriage on the radio that would be grounds for divorce in any civilized land.

In 1981, Howard arrives at a Washington, D.C., station and is paired for the first time with Robin Quivers, who plays herself in the movie and functions as ballast, steadying Howard in his manic phases and speaking for many members of the audience when she tells him, over and over, that this time he’s gone too far. Stern and Quivers are both making their screen acting debuts here, and they do what seasoned actors claim is very difficult: They play convincing, engaging versions of themselves.

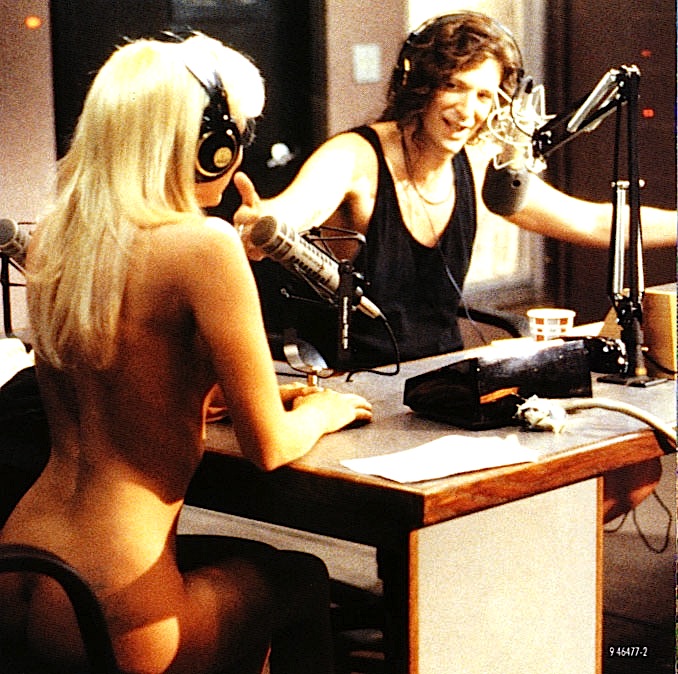

The final third of the movie shows Howard in his modern incarnation, as the shock jock who will say almost anything on the radio. He crowns himself King of All Media (tough to do, since by his account he rarely has both hands free at the same time). And he gets into trouble after WNBC, the network’s New York flagship, hires him apparently without having listened to his show. His new boss is a program director quickly nicknamed Pig Vomit (well played by Paul Giamatti), who promises his superior, “Either I tame him or I make him so crazy he quits.” The process includes lessons in the proper singsong pronunciation of the call letters.

When one bit goes over the top, Howard makes Robin the fall guy. She’s fired and feels betrayed. This episode, based on life, is played honestly; Howard acts like a creep and doesn’t resign on principle, although perhaps he is right, strategically, to see the firing as a ploy to get him to resign.

The film has been directed by Betty Thomas (“The Brady Bunch,” “The Late Shift”), whose steadying hand makes it play like a movie and not a series of filmed radio shows. Many sequences are very funny, including one where Howard uses a listener’s subwoofer to create effects for which it was not designed.

Stern on-air regulars like Fred Norris and Jackie “The Joke Man” Martling play themselves, and Gary Dell'Abate hosts inserts that feel unrehearsed, including one where a donkey makes a surprise appearance.

Stern reportedly rejected two dozen scripts before settling on this one, written by Len Blum. He made the prudent choice. The material is just outrageous enough to be convincingly Stern, but not so far out it will offend those likely to see this movie (the current “Booty Call,” by contrast, is more uninhibited). The movie successfully launches Stern’s screen career, and it will be interesting to see how its inevitable sequel, “Miss America,” will develop.

What is certain is that Stern will find a way to stretch the envelope without tearing it; he may have been fined $1 million by the FCC, as his publicity boasts, but he is still, after all, on the air.