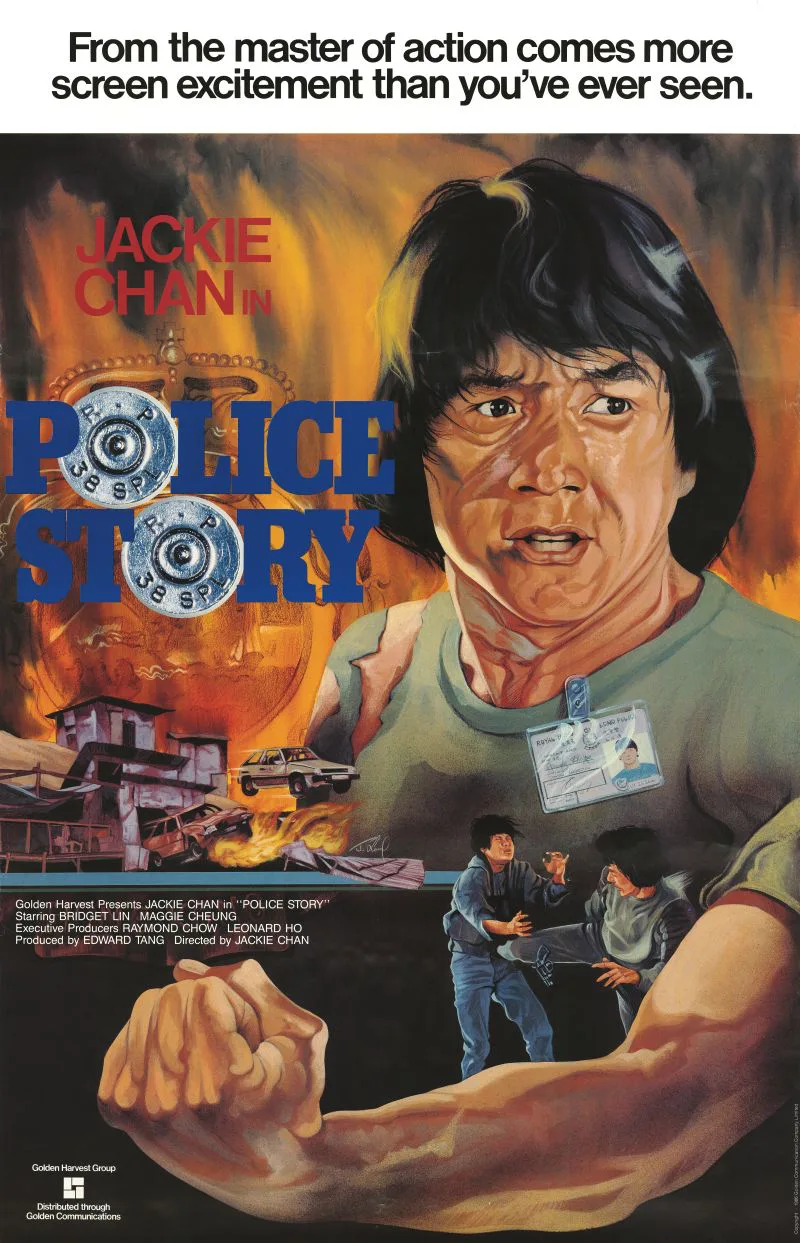

Jackie Chan‘s “Police Story” is one of the great 1980s action films. It’s also one of the most 1980s action films. It’s a bundle of cop-on-the-edge clichés that climaxes with Chan’s Hong Kong policeman hero at war with both his by-the-book superior officers and the crime lord villain who remains stubbornly beyond the law’s reach. The synthesized score is music to mousse one’s hair by. Like many Chan films from this period of his career, it ends with a freeze-frame, followed with outtakes of Chan and his fellow performers goofing around on set and getting injured, scored to a pop song sung by Chan himself.

But—as is the case with most memorable comedies, as well as most memorable thrillers—the excellence of “Police Story” has nothing to do with what kind of movie it is, and everything to do with how it’s executed. Like most of Chan’s signature films, this one is driven by his ingenuity as an athlete, stunt choreographer, and director.

The plot finds Chan’s character, Kevin Chan, trying to protect state’s witness Selina Fong (Bridgett Lin), girlfriend of gangster Chu Tao (Chor Yuen), from being abducted and killed before she can testify at a trial. There are a lot of twists in the script, but it’s ultimately less of a fully developed story than a narrative through-line upon which Chan can hang a series of self-contained set-pieces that showcase varieties of physical acting, from stage-fighting and death-defying stunt work to pratfalls and corny bits of shtick.

“Police Story” starts and ends with prolonged, elaborately choreographed, exceptionally violent sequences in which, respectively, a mountainside village and a department store are destroyed. The rest is a series of equally ludicrous but smaller-scaled encounters, some modeled on screwball comedies, others on shenanigans churned out during the first half of the 20th century by screen comics like Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, the Three Stooges, and Chan’s personal god, actor/director/stunt performer Buster Keaton. Like most Hong Kong action stars of his generation, Chan was trained by the Peking Opera Company as an all-purpose, variety show-type of performer who can do pretty much anything with his body and is eager to prove it. The entire film has the mentality of a master showman who wants to dazzle in every moment, big or small. During the long, farce-dominated middle section of “Police Story,” Chan will occasionally throw in a brief, small-scale action scene, like the one where his character fights a bunch of guys in a parking lot, as if to reassure moviegoers who are only here for the punch-outs, car crashes, and wild stunt work that he hasn’t forgotten about them. But they’re just one flavor in the smorgasbord.

The crime lord’s attorney makes like a Marx brother in court, twisting language and logic into pretzels to make his obviously guilty client seem innocent. Kevin’s girlfriend May (Maggie Cheung), who thinks Kevin’s cheating on her with Selina, argues with him on a steeply angled street while Kevin leans into the open passenger-side window of his car, serving as a human set of brakes because he accidentally left the vehicle in neutral. In an especially weird and abrasive slapstick scene, Kevin asks a colleague to pretend to be a home-invading assassin to make Selina accept him as her protector; it plays like something out of a horror spoof like “Scary Movie.” There’s even a little “solo” in which Kevin tries to keep three phone conversations going while rolling around the squad room in a desk chair and getting tangled up in the cords. (Fred Astaire and Charlie Chaplin used to allow themselves these sorts of intimate showcases, turning ordinary objects such as coat racks or dinner rolls into scene partners.)

At any given moment, a character is equally likely to bonk their head on a door or get pushed through a series of plate glass windows. There are anguished scenes of Kevin getting betrayed by a coworker and seeing his stolen sidearm used in a murder that could’ve appeared in a hardcore ‘80s urban thriller like “Nighthawks” or the original “48 HRS,” and they coexist with a romantic comedy-style birthday party-gone-awry in which Kevin gets a series of cakes thrown in his face, as well as a scene where Kevin steps in cow manure and moonwalks his way out of it. Sometimes the film’s humor is knowingly naïve, even childlike. Other times it’s spectacularly brutal, or nearly Chaucerian in its nastiness, as if we’re seeing a morality tale about the miseries that accrue when you mistreat others. The misfortunes Kevin suffers during the film’s second half sometimes feel like cosmic punishment for his bratty behavior during the first half.

We never know what madness awaits. Whatever happens, we’re supposed to just accept it. And we do, mostly, because this is a Jackie Chan film. There are a few elements that seemed merely bawdy in 1985 but that sit uncomfortably today, like the two citizens who call Kevin during the phone scene, one reporting a domestic violence incident, the other a stolen cow. But these seem of a piece with Kevin shattering a glass window with his face and a man getting tossed down an escalator and sliding to the next floor in the little space between the up and down sides. This is vaudeville stuff, circus stuff, Punch and Judy, the Stooges. It’s primordial.

Chan exists to impress us, and impress he does. He literally suffers for his art, and our amusement. The opening action sequence kicks off with a gun battle in a crowded mountainside village; builds toward a car chase, with cops and criminals plowing through the sides of buildings, detonating propane tanks and flattening shanty homes as they go; and ends with Chan trying to head off a hijacked city bus by racing up and down a series of steep hills (like Indiana Jones going after the Ark of the Covenant, but without the horse). The shopping mall fight at the end is a masterpiece of choreography that treats agonized screams, shattering glass, and flickering slow-motion as percussion elements, like cymbal crashes in a drum solo. A stunt near the end gets repeated at full length three times, from three different angles; this would seem like a display of narcissism if it weren’t one of the greatest stunts in the history of movies, right up there with the collapsing house in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” and the final fall in “Sharky’s Machine.” There’s no sleight-of-hand involved in this magic, just death defying stunt work and efficient filmmaking that helps you appreciate it.

A new 4K restoration of “Police Story” opens at the Metrograph this Friday, March 9th.