“Plunkett and Macleane” conducts an experiment: Can a movie be constructed entirely out of stylistic excess, without the aid of a story or characters we’d give two farthings for? Answer: Perhaps, but not this time. Here is a film overgrown with so many directorial flourishes that the heroes need machetes to hack their way to within view of the audience. It’s not enough to want to make a movie. You have to know why, and let the audience in on your thinking.

The film, set in 18th century London, tells the story of a gentleman named Macleane (Jonny Lee Miller) and an unwashed rogue named Plunkett (Robert Carlyle). Macleane is not entirely a gentleman (the movie opens with him being sentenced for public drunkenness), but at least he knows how to play one, and the accent is right. Plunkett has the better natural manners and charm. When they meet after an unlikely jailbreak, Plunkett suggests that with Macleane’s accent and his own criminal expertise, they could make a living stealing from the rich.

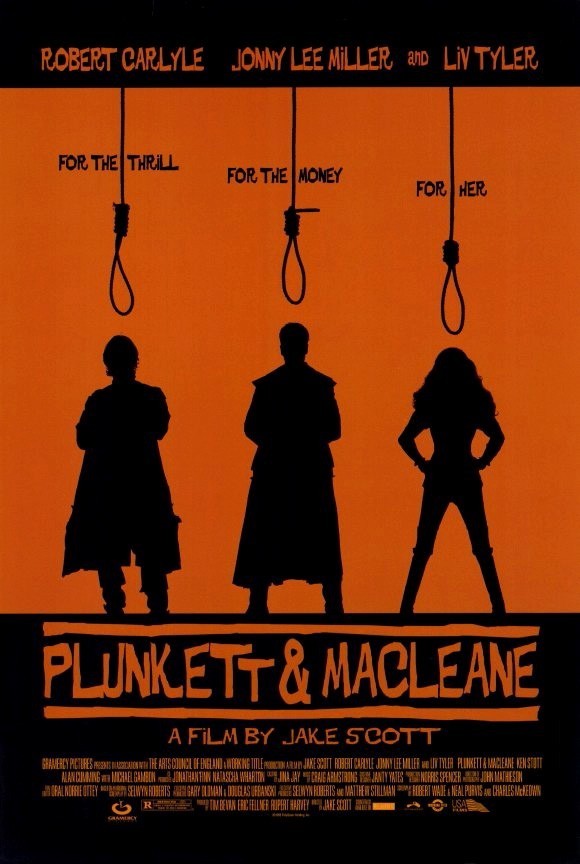

When you extract this story from the morass of style through which it wades, it’s as simpleminded as an old B Western. The two men lurk in the woods, spring upon the passing carriages of the rich, and relieve them of their wealth. Trouble looms when Macleane is smitten by the beautiful Lady Rebecca Gibson (Liv Tyler), who, wouldn’t you know, is the niece of the Lord Chief Justice (Michael Gambon). The pair become known as the Gentlemen Highwaymen, the chief justice is enraged that they have not been captured, and the oily Chance (Ken Stott) is in charge of the chase.

Just as a random hypothesis, let us suppose that one of the pair is captured and sentenced to hang. Take the following multiple-choice quiz. Will he: a. Hang by the neck until dead.

b. Escape in a daring jailbreak.

c. Receive a pardon on the tearful entreaties of Lady Rebecca.

d. Mount the gallows tree, have the noose slipped around his neck, have the trap door opened, fall to the end of the rope, and hang there for long seconds, before being cut down in a tardy last-moment rescue plan, leaving us in suspense about whether he is dead or alive (unless we have studied the immutable movie genre laws governing such matters).

I will publish the answer at the end of the next millennium or when the sequel to this movie is released, whichever comes first.

“Plunkett and Macleane” was directed by Jake Scott, son of Ridley Scott, whose own films (“Alien,” “Blade Runner“) are themselves dripping with dark, gloomy atmosphere, but who knows how to tell a story about interesting characters (“Thelma & Louise”). The problem with Jake Scott is that he uses background as foreground. There are times early in “Plunkett and Macleane” when there are so many mysterious and opaque objects cluttering the screen that, as we try to peer around them, we wonder if the MPAA warmed up on this movie before obscuring the naughty bits in “Eyes Wide Shut.” Dialogue and character are always secondary to atmosphere. The highwaymen and their prey are seen through a murk of fog, mist, overgrowth, lantern shadows, bric-a-brac, triglyphs and metopes; their dialogue has to be barked out between the sudden arrival of more visual astonishments. The soundtrack is cluttered with a lot of anachronistic music, as if the movie began life as an MTV music video and then had its period violently wrenched back into the past before the contemporary music could be removed. How displaced is the music? The movie is set in 1748, but the song under the credits, if I heard correctly, mentions the Jedi.

If there’s one thing that annoys me in a movie (and there are many in this one), it’s when the characters escape through a loophole in the cinematic technique. There’s a scene where Plunkett and Macleane are trapped inside a carriage, which is riddled with countless bullets, just like a car in a gangster movie. The carriage is surrounded. When it is approached after the fusillade, Plunkett and Macleane have disappeared and been replaced by a bomb with a burning fuse! How? Is this not physically impossible? We’re not even supposed to ask, because we are so very, very entertained by such a clever, clever surprise. My movie history may be shaky, but I believe this sequence was inspired by a Looney Tune.