I’m writing this review from London, where the papers for the last few days have been filled with the scandal of the Conservative member of Parliament who had to resign his constituency after being convicted of spanking two male prostitutes who were younger than 21, which is the age of consent for homosexual spankings in Britain. (Female prostitutes can legally be spanked once they are 16. There’ll always be an England.)

This morning on the radio, they interviewed Cynthia Payne, who said she was shocked that this fine public servant had to have his reputation ruined: “What’s wrong with wanting to slap somebody’s bottom once in a while, so long as no harm is done? We all have our peculiarities, we just cover them up, that’s all.” She sounded just like all other housewives on the call-in show.

This was the same Cynthia Payne who has become something of a folk legend over here for operating what the tabloids called “the House of Cyn,” a brothel catering to middle-age and elderly gentlemen with rather specialized tastes. Nicknamed the “Luncheon Voucher Madame” because she sometimes charged as little as you’d pay for a nice plate of sausages-and-mashed, Payne was acquitted on her latest round of charges last January and greeted outside the law court by a street full of her cheering supporters.

Payne has always insisted she did not engage in sex herself and did not supply sex to her clients. Instead, there were naughty fashion shows featuring lace undies, see-through nighties and leather corsets. Also available were such specialties as charging men for the privilege of doing the housework and weeding her garden. Military men and successful businessmen were especially keen for the humiliation; it took their minds off their responsibilities.

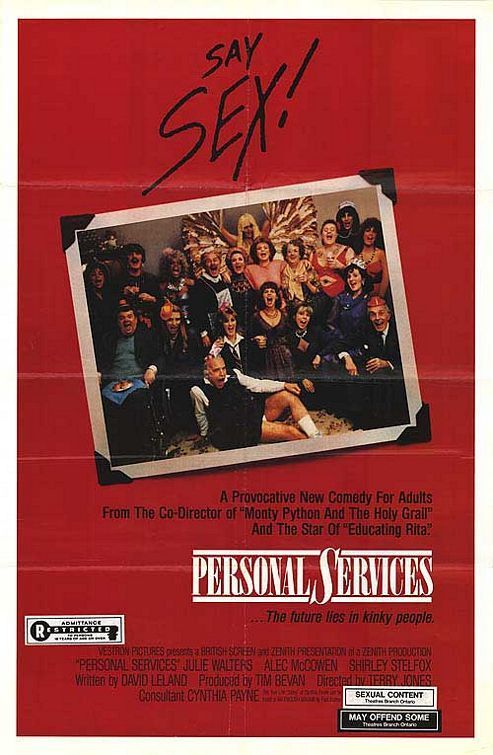

“Personal Services,” by the Monty Python veteran Terry Jones, is an attempt to explore the peculiarly mercenary world of Payne. She is called “Christine Painter” in the movie but nevertheless is listed as an adviser and will be in New York this week on a public relations tour. She began as a waitress who invested her savings in cheap flats and only got into the brothel-keeping business because hookers paid their rent on time.

As the movie tells it, Payne never really even intended to go into business; she just kept running across nice gentlemen who liked a bit of naughtiness once in a while. She preferred older gentlemen; they caused less trouble and were more grateful. And, as she told the court, an evening at the “House of Cyn” simply involved having a few old friends over for a party. It was all very innocent; they preferred their crumpets with tea.

“Personal Services” is not a sensational movie, nor does it want to be. It is a study of banality, with flashes of genuine comedy, as when a retired war hero (Alec McCowen) takes the press on a tour of the House while singing the praises of transvestism.

The heroine is played by Julie Walters, recently seen in the Oscar-nominated title role of “Educating Rita,” and she has it just right: the tight lips, polite reserve, the proper manner and bearing, all designed to keep passion and sex in different departments, where they belong.

The British law, on the other hand, comes across as more obsessed by sex than anyone at the madam’s parties. Plainclothesmen infiltrate the goings-on and deliver breathless accounts of whips and leather knickers. Many of the clients are only too happy to go into the dock and testify to the underlying innocence of their particular hobbies, and by the end of the film there is the suggestion that the heroine probably will keep right on doing what she does best: having friends in for little parties. Which, as it turned out, was exactly what happened.