A man walks alone in the desert. He has no memory, no past, no future. He finds an isolated settlement where the doctor, another exile, a German, makes some calls. Eventually the man’s brother comes to take him back home again. Before we think about this as the beginning of a story, let’s think about it very specifically as the first twenty minutes of a movie. When I was watching “Paris, Texas” for the first time, my immediate reaction to the film’s opening scenes was one of intrigue: I had no good guesses about where this movie was headed, and that, in itself, was exciting, because in this most pragmatic of times, even the best movies seem to be intended as predictable consumer products. If you see a lot of movies, you can sit there watching the screen and guessing what will happen next, and be right most of the time.

That’s not the case with “Paris, Texas.” This is a defiantly individual film, about loss and loneliness and eccentricity. We haven’t met the characters before in a dozen other films. To some people, that can be disconcerting; I’ve actually read reviews of “Paris, Texas” complaining because the man in the desert is German, and that another character is French. Is it written that the people in movies have to be Middle Americans, like refugees from a sitcom?

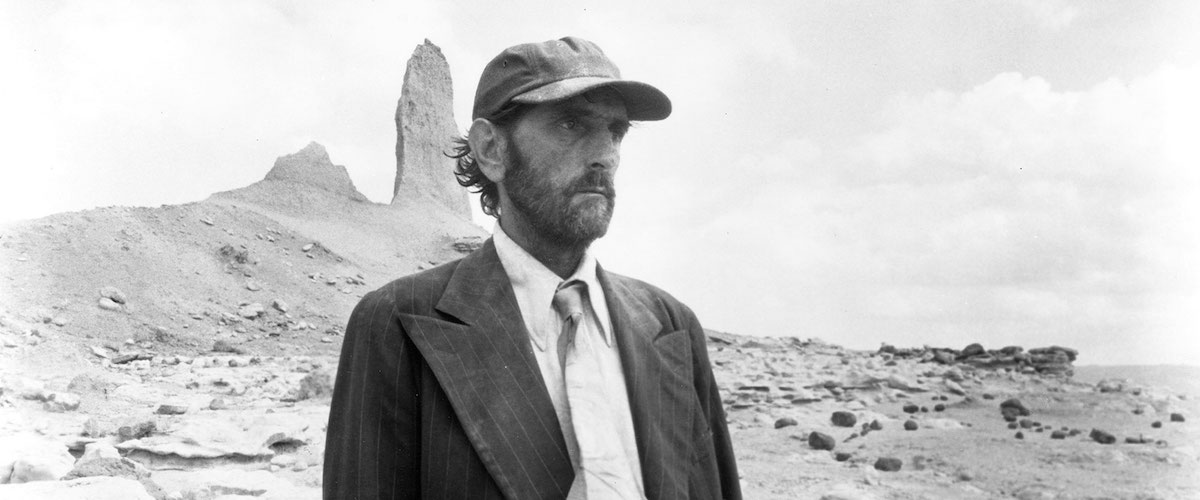

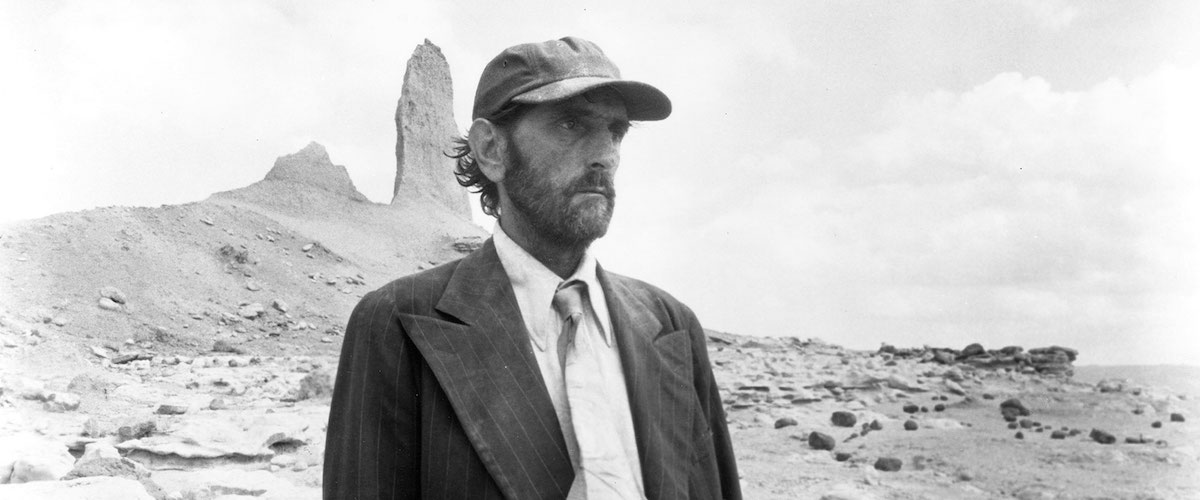

The characters in this movie come out of the imagination of Sam Shepard, the playwright of rage and alienation, and Wim Wenders, a West German director who often makes “road movies,” in which lost men look for answers in the vastness of great American cities. The lost man is played this time by Harry Dean Stanton, the most forlorn and angry of all great American character actors. We never do find out what personal cataclysm led to his walk in the desert, but as his memory begins to return, we learn how much he has lost. He was married, once, and had a little boy. The boy has been raised in the last several years by Stanton’s brother (Dean Stockwell) and sister-in-law (Aurore Clément). Stanton’s young wife (Nastassja Kinski) seems to have disappeared entirely in the years of his exile. The little boy is played by Hunter Carson, in one of the least affected, most convincing juvenile performances in a long time. He is more or less a typical American kid, despite the strange adults in his life. He meets Stanton and accepts him as a second father, but of course he thinks of Stockwell and Clément as his family. Stanton has a mad dream of finding his wife and putting the pieces of his past back together again. He goes looking, and finds Kinski behind the one-way mirror of one of those sad sex emporiums where men pay to talk to women on the telephone.

“Paris, Texas” is more concerned with exploring emotions than with telling a story. This isn’t a movie about missing persons, but about missing feelings. The images in the film show people framed by the vast, impersonal forms of modern architecture; the cities seem as empty as the desert did in the opening sequence. And yet this film is not the standard attack on American alienation. It seems fascinated by America, by our music, by the size of our cities, and a land so big that a man like the Stanton character might easily get misplaced. Stanton’s name in the movie is Travis, and that reminds us not only of Travis McGee, the private eye who specialized in helping lost souls, but also of lots of American Westerns in which things were simpler, and you knew who your enemy was. It is a name out of American pop culture, and the movie is a reminder that all three of the great German New Wave directors — Herzog, Fassbinder, and Wenders — have been fascinated by American rock music, American fashions, American mythology.

This is Wenders’s fourth film shot at least partly in America (the others were “Alice in the Cities,” “The American Friend,” and “Hammett”). It also bears traces of “Kings of the Road,” his German road movie in which two men meet by chance and travel for a time together, united by their mutual inability to love and understand women. But it is better than those movies — it’s his best work so far — because it links the unforgettable images to a spare, perfectly heard American idiom. The Sam Shepard dialogue has a way of allowing characters to tell us almost nothing about themselves, except for their most banal beliefs and their deepest fears.

“Paris, Texas” is a movie with the kind of passion and willingness to experiment that was more common fifteen years ago than it is now. It has more links with films like “Five Easy Pieces” and “Easy Rider” and “Midnight Cowboy,” than with the slick arcade games that are the box-office winners of the 1980s. It is true, deep, and brilliant.