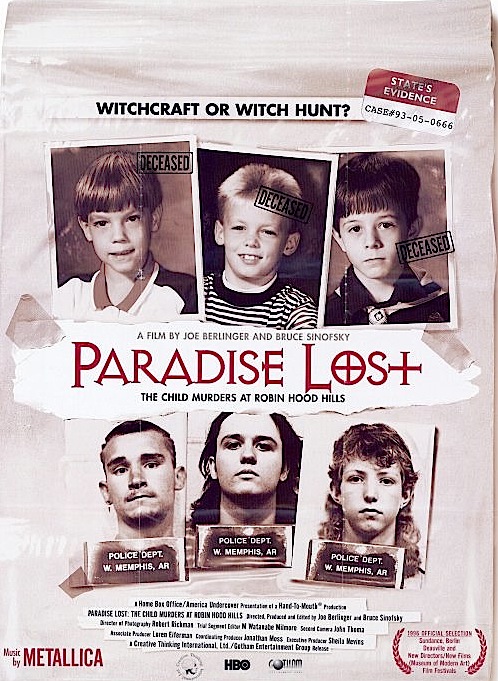

“Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills” is unique among courtroom documentaries in that the filmmakers, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, seem to have had complete access to both sides of the trial process, including private family meetings, conferences with lawyers, even sessions in the judge’s chambers. The film opens with sad police video footage from the crime scene, showing the bodies as they were first discovered, and then reports how wild rumors swept the area about satanic rituals, animal sacrifice and blood drinking.

A month after the murders, an undersized 17-year-old named Jesse Misskelly, with an IQ of 72, testified that he had been present when Damien Wayne Echols, 18, and Jason Baldwin, 16, killed and mutilated the boys. Local prosecutors brought murder charges against the boys. In the courtroom, they make a poignant trio: Jesse, small and blinking; Jason, who does not testify and indeed hardly speaks except in soft, shy generalities, and Damien, intelligent and articulate, known locally for dressing in black, listening to heavy metal music and reading books on Wicca, or “white magic.” There is no significant physical evidence linking them to the crime, and the crime scene itself is without clues. Although one of the victims lost five pints of blood and the others bled freely, there is no blood at the murder site. The state’s case is based on Jesse’s testimony and hearsay; the defense argues that the statements made by Jesse contained only facts first supplied to him by the police, and there is a fascinating cross-examination in which a police transcript shows Jesse shifting the time of the crimes from morning to noon to after school to evening (when they actually occurred) under leading suggestions by police.

Jesse, whose trial was split off from the others, was found guilty and sentenced to life plus 40 years. He was offered a reduced sentence if he would testify at the trial of the other two teenagers, but refused. His mother says she told him she would be sitting right there in the courtroom, and didn’t want to hear him lie.

At the trial of Damien and Jason, evidence of the satanic orientation of the murders is supplied by a state “expert occultist” who turns out to have his degrees from a mail-order university that did not require any classes or schoolwork. For the defense, a pathologist testifies that it would be so difficult to carry out the precise mutilations on one of the boys that he couldn’t do it himself–not without the right scalpel, and certainly not in the dark or in muddy water.

Meanwhile, we meet members of the families on both sides. Time and again, the documentary describes someone as a boyfriend, girlfriend, stepfather, stepmother, ex-wife or ex-husband; there seem to be few intact original marriages in this milieu. The parents of the murdered children are quick to believe the theories about the crime, and unforgiving. One mother says of Damien, “He deserves to be tortured for the rest of his life.” She curses not only the defendants, “but the mothers that bore them.” In one especially uncomfortable scene, relatives of two of the victims take target practice by shooting at pumpkins they have named after the defendants, aiming at parts of the “bodies” they have not yet hit.

One of these men is John Mark Byers, stepfather of one of the victims, who earlier has been seen in a video at the crime scene, re-creating the crimes in grisly detail while vowing vengeance. In the movie’s single most astonishing development, Byers gives the filmmakers a knife. They turn it over to the state. Crime lab reports show traces of blood that apparently came from himself and his stepson. On the witness stand, he testifies that he beat his stepson with a belt at 5:30 p.m. on the day of his death. The welts from the belt buckle previously had been linked to the ritual killing.

We would like to hear testimony from Byers about whether the other victims were then present, or if his stepson later joined them, and where they were later, and where he was. Either those questions were not asked, or the filmmakers decided not to use them. One of the frustrating things about “Paradise Lost” is that, for all the information it contains, key elements are missing. The three defendants, for example, all claim to have alibis for the night of the murder, but we learn little about them.

The film ends with guilty verdicts against Damien (death by injection) and Jason (life in prison). The sentences are under appeal. At the end of the film I was unconvinced of their guilt.

The film creates a vivid portrait of a subculture in which Satan is a central figure. Where did Damien, Jason and Jesse hear about satanic rituals? Mostly in church, it would appear. Some members of this community seem to require Satanism as part of their world view; they seize upon the devil to explain what dismays them. Their frequent theme is vengeance, and it is blood-curdling to hear relatives of the victims promise that if the defendants are released, they will track them down and kill them.

The only person in the film who defends a traditional Christian belief system is the grandfather of one victim, who says he believes in forgiveness, and knows he will be reunited in heaven with his loved ones. The others in the room listen without comprehension. We leave the film unsure about who committed the murders, but convinced that an obsession with Satanism extends here far beyond the circle of defendants.