Crazy, violent and shocking events go down in “Paradise: Faith”—events that will startle the devout and non-believers alike—but Austrian director Ulrich Seidl depicts them all with same sort of monotone detachment he uses in the film’s more mundane moments.

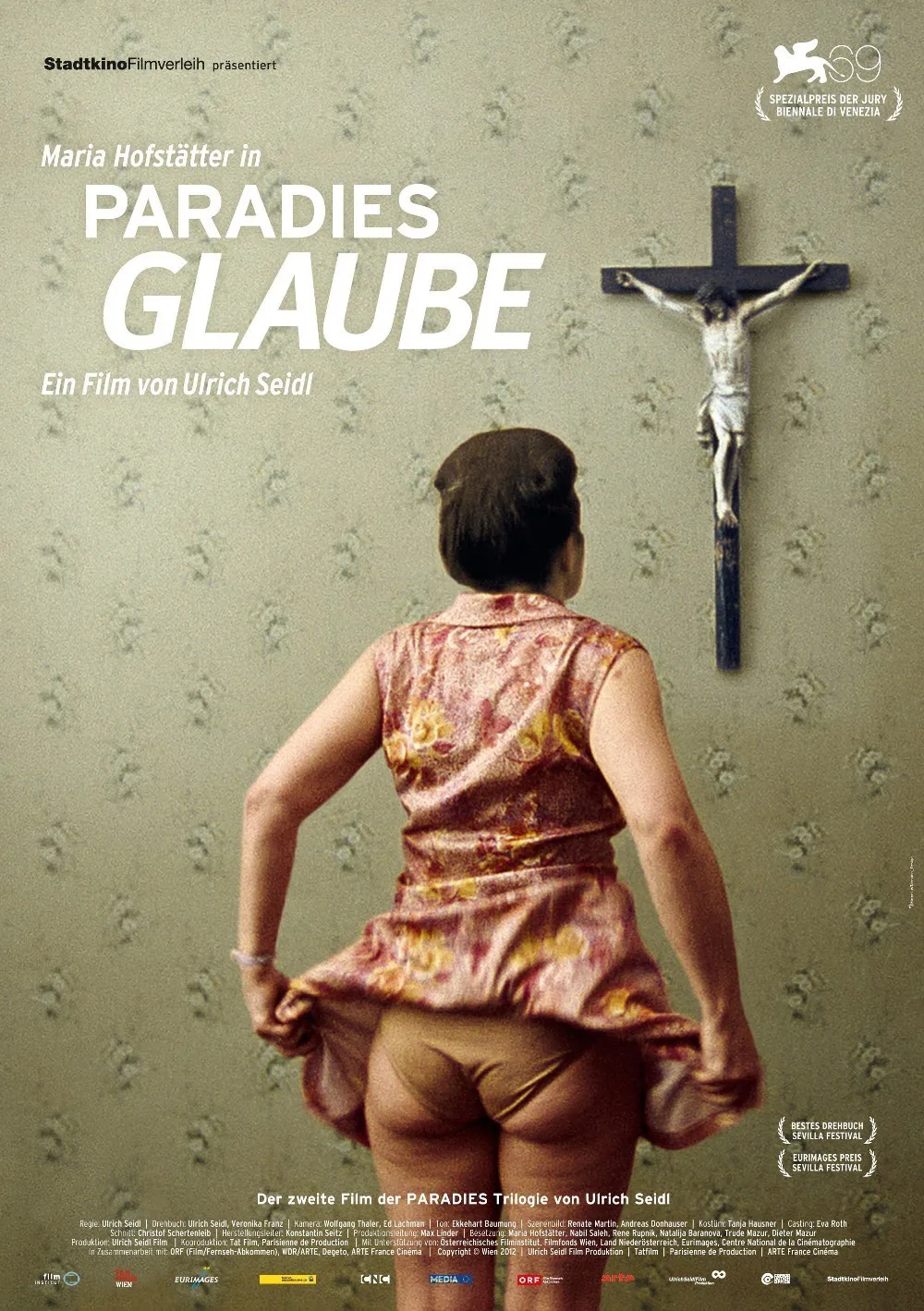

It’s hard to tell what Seidl thinks of his heroine, the prim and pious Anna Maria, played with fierce dedication by veteran character actress Maria Hofstatter. He shoots her from far away, often from behind, with long static takes that allow us to take in the precision of her actions and surroundings. Is she a decent, old-fashioned woman who dares speak from the heart in a cynical world? Or a sad and frightening example of religious devotion gone mad?

She might be both—and the fact that Seidl doesn’t judge her allows us to ponder the many complex shadings of a woman who, from all outside appearances, would seem rather ordinary and boring. The middle-aged Anna Maria almost exists in a time warp with her conservative wardrobe and structured up-do. The only decorations in her modest, meticulously tidy house are the crucifixes that adorn each room (although the framed photograph of the pope in the kitchen is a nice touch).

“Faith” is the second installment in Seidl’s trilogy of “Paradise” films about women who are seekers; “Love” was the first, “Hope” the second. He makes his features with a documentary aesthetic, mixing actors and non-actors who improvise their dialogue based on an outline. And indeed, this stripped-down approach does provide the sensation that anything could happen at any moment.

Scenes are dramatic without a hint of melodrama, so when a flash of intensity does occur, it does so out of nowhere and registers even more powerfully. On the flip side, though, Seidl allows some of his scenes to drag on far longer than necessary, to the point where they almost feel like a test of stamina. We’re left wondering whether he’s admiring Anna Maria for her dedication or gawking at her.

Anna Maria tests herself, physically and spiritually, by spending her vacation from her job as an X-ray technician traveling door to door through the tenements of Vienna. She carries with her a 16-inch statue of the Virgin Mary and insists on praying with whomever answers. Sometimes, the residents let her in and go along with her in bewildered silence. Others question her, like the elderly divorcee and widower who laugh at her archaic but earnest assertion that they’re living in sin.

Still others close the door in her face immediately and send her away (which, frankly, would be my response). Anna Maria remains undaunted and sweetly, creepily ingratiating; after all, she’s part of a prayer group on a crusade to make Austria an entirely Catholic country. She’s got work to do.

But Anna Maria has a dark side, as Seidl indicates in the film’s opening sequence in which she enters a spare bedroom, strips to her waist, kneels before a cross and repeatedly self-flagellates with a cat o’ nine tails for some vague, unchaste act.

“Thank you, Jesus,” she says afterward, her back radiating with red slashes. “Thank you.”

And this is only the beginning.

Anna Maria finds her routine disrupted, though, when she comes home and discovers an elderly man sitting in a wheelchair in her living room. He is an Egyptian Muslim named Nabil (Nabil Saleh), and as it turns out, he’s her husband. Seidl takes his time disclosing what happened to him and where he’s been, but the awkwardness of reconciliation is immediate and undeniable.

“You weren’t this way before,” Nabil eventually asks once he realizes what his wife’s life has become. “What kind of religion is this?” But instead of exploring the sort of fundamental conflict between Christianity and Islam that you might expect, Seidl seems more interested in finding out what happens when estranged spouses with nothing in common anymore must learn to coexist in a confined space—or not.

He puts both his lead actors through the wringer, and their perseverance is even more impressive given that Saleh is a masseur by trade, making his film debut. But rather than feeling like a stunt—or a holy “War of the Roses”—”Paradise: Faith” considers both the best and the depth of humanity and suggests that perhaps they aren’t so far apart after all.