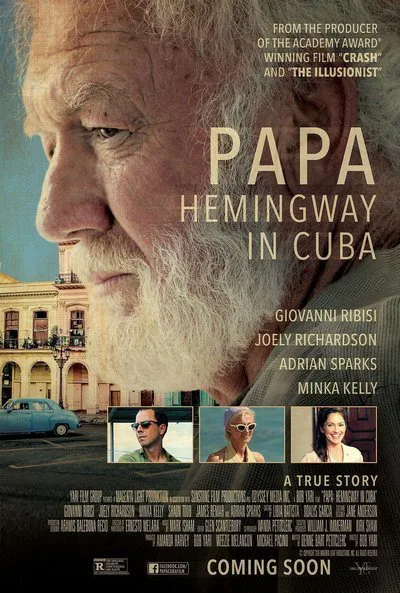

There’s no doubt that “Papa: Hemingway in Cuba” seemed promising on paper. The script was written by Denne Bart Petitclerc and was based on his own experiences with Ernest Hemingway, whom he befriended as a young journalist. Petitclerc passed away a decade ago, and he would’ve been thrilled to learn that the long belated project would become the first Hollywood film shot in Cuba since 1959, and that various scenes would be shot in the locations where Hemingway once resided. Even Mariel Hemingway, the writer’s granddaughter, turns up in an all-too-brief cameo. These behind-the-scenes factoids are the most interesting aspects of the film—and, regrettably, the only interesting aspects, as well.

Likening “Papa” to a made-for-TV movie would be inaccurate, considering how cinematic TV has become in recent years, and how many programs are oftentimes superior to typical theatrical offerings (look no further than this year’s inaugural season of “American Crime Story” for sufficient proof). “Papa” is merely cinema at its dullest, a perfunctory assemblage of biographical bullet points in which characters explain their lives rather than live them. Petitclerc’s fictionalized self is inexplicably renamed Ed Myers and played by Giovanni Ribisi in a performance so wooden, he occasionally resembles the wax dummy of Joseph Cotten. Myers owes his entire career to Hemingway, and has obsessed over crafting the perfect letter to his hero. When his girlfriend, Debbie (Minka Kelly), secretly mails the letter, Hemingway is so impressed with it that he calls Myers and invites him on a fishing trip. The fact that we never see the contents of the letter is a prime example of how the storytelling continuously keeps us at arm’s length, never allowing us to fully understand the bond that developed between these men.

Rather than pause for a few beats that would allow Myers and Hemingway to feel each other out during their initial encounter, the film cuts abruptly to a comedic fishing sequence that is punctuated with a punchline delivered by Hemingway. Adrian Sparks does all he can with a role comprised of either wise platitudes or self-destructive outbursts. Take a fleeting glimpse at any given shot of Ribisi and Sparks aboard a boat, and you’d swear you were looking at Roy Scheider and Robert Shaw in “Jaws” (albeit without a shark, alas). Sparks growls his lines with a campy surliness in scenes where he’s required to “be a prick,” and then turns on a dime to a paternal warmth when conversing with “the kid.” At age 41, Ribisi lacks the boyish qualities needed to be regarded as “a kid,” and it’s worth noting that Petitclerc was in his 20s during the events depicted here. A series of forced chuckles and bare bottoms are utilized to suggest a sense of intimacy among the characters, but when it comes to delving into their relationships, the script remains at surface level. It’s clear that Petitclerc’s draft was in need of a rewrite.

Peter Greenaway’s “Eisenstein in Guanajuato” may have fallen short as a biopic, but as a frank portrayal of a man’s sexual awakening, it was vividly realized and wholly memorable. There’s not a single frame of “Papa: Hemingway in Cuba” that is guaranteed to linger long in the memory. The director here is Bob Yari, who has found great success as a producer of terrific films such as “Thumbsucker,” “The Painted Veil” and “Nothing But the Truth.” This is his first directorial credit since 1989’s “Mind Games,” and on the basis of this picture, he should stick to producing. The film is not incompetent per se, aside from the truly awful sound design on the screener that I viewed (hopefully these errors will be cleaned up in subsequent prints). Dueling ambiences were clashing every time the characters opened their mouths, but more importantly, what they had to say just wasn’t very interesting. Here’s a film about one of the greatest writers in history that reduces the iconic man’s mind to the canned insights of a fortune cookie. In what should’ve been a compelling scene, Hemingway opens up to Myers about an act of infidelity that has haunted him throughout the years. “Make a decision carefully,” he cautions Myers. “Consider every consequence.” Contrast these generic declarations with Jason Robards’ shattering monologue in “Magnolia,” which recounts similar wounds with a rambling tone and naturalistic poetry that feels like it was ripped directly from the dying man’s soul.

Jason Isaacs once told me that no actor, however good, can make a bad script work, and I kept being reminded of his words while watching “Papa.” Faced with stilted dialogue, Sparks and Joely Richardson (as Hemingway’s wife, Mary) overact in order to compensate. Both of these people are very good actors, and it’s painful to watch them wrestle with subpar material. The best scene, by far, is the only one that hints at Hemingway’s genius. In order to illustrate the power of less, Hemingway writes a fully realized story in only six words: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” That’s a great line, though in the case of Petitclerc’s shallow characterizations, less is definitely less.