What we have here, depressing and harrowing and often very real, is the other side of the coin of “Breaking Away.” That movie was a celebration of the possibilities involved in coming of age in a small town. “Over the Edge” is a funeral service held at the graveside of the suburban dream. It tells a ragged story that ends with an improbable climax, but it’s acted so well and truly by its mostly teen-age cast that we somehow feel we’re eavesdropping.

The movie’s set on those dry, rolling plains west of Denver, where suburbia creeps toward Boulder, and Boulder creeps back. The name of this suburb is New Granada—an oasis of split-level homes and streets curving gracefully toward their dead-ends at the end of the development. The soft plops of tennis balls tick away the afternoons. Oh, and there are kids here, too. They hang out at a Quonset hut that’s the local youth center, and if you know the right kid you can get a deal on grass, hash, ludes, speed, whatdaya need?

The parents are concerned about the “youth problem.” So are those adults delegated to hold the local kids in check: The cops and the schoolteachers. The cops aren’t intrinsically evil; they just know a lot more about police methods than about human nature. The teachers are all but defeated by an openly defiant student body. Most of the kids, I should add, aren’t really that bad: It’s just that they feel unwelcome, somehow, when the youth center is shut down the day Texas investors visit New Granada, so the Texans won’t think the suburb is infested by teen-agers.

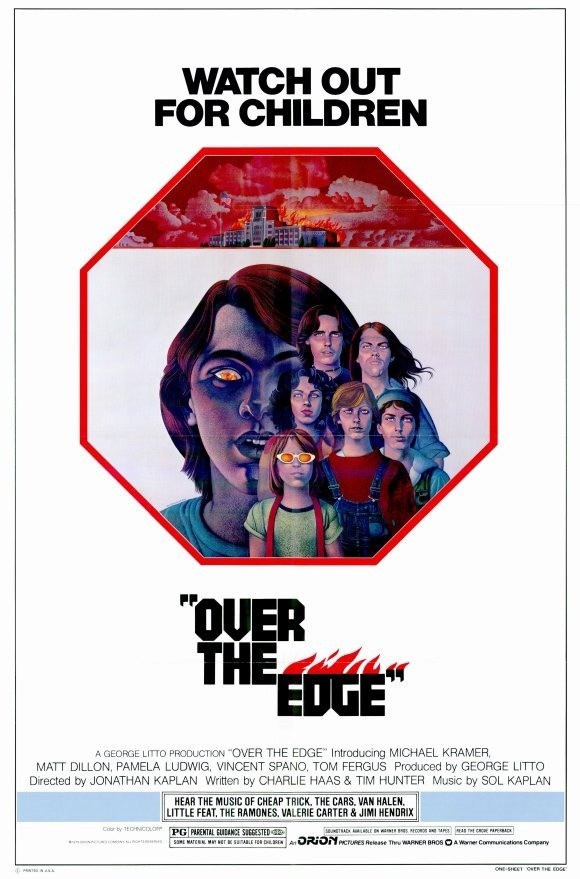

The story involves a basically good kid named Carl (Michael Kramer), who’s in with the wrong crowd—kids who deal dope and play around with a gun one of them stole from someone’s home. Carl’s parents love him, after the fashion of parents driven up the wall by teen-agers, but they despair of keeping him out of trouble. The only person who understands Carl, in a visceral, instinctive way, is his girl friend, Cory (Pamela Ludwig). Their scenes together have a wonderfully understated authenticity. Then one of Carl’s friends is busted, another one is arrested for carrying a switchblade, and Carl gets involved in a very nasty situation in which a cop shoots one of his friends. All of this is on the way toward the apocalyptic ending that the movie’s ads found promotable.

The particulars of the plot aren’t all that important; we’re supposed to absorb a feeling of teen-age frustration and paranoia, and we do. The violent climax is particularly unconvincing, as if the director, Jonathan Kaplan, thought he had to throw in a bunch of exploding gas tanks at the end of the film to take the curse off of his basically serious and honorable intentions. But the plot and the climax aren’t what this movie is really about. It’s about the rhythms of teen-age life, about how kids talk and feel and yearn, about the maddening sensation of occupying a body with adolescent values but adult emotions.

“Over the Edge” does an uncanny job of portraying these kids in a recognizable, convincing way. The screenplay was a writing debut by Tim Hunter, who went on to direct “Tex” (1982, starring Matt Dillon, who was discovered in “Over the Edge” and “River’s Edge,” 1986, both also about confused teenagers.) There were several movies released at about the same time as “Over the Edge” about kids more or less in the same age bracket. “A Little Romance” gave us kids who were completely a figment of romantic middle-aged fantasies. “Rich Kids” (1979) gave us precocious Manhattan kids who probably already smile with recognition at cartoons in the New Yorker. “Breaking Away” gave us kids who are a little older, more mature, more aware of how they are behaving. But “Over the Edge” is about kids who might—who, God help us and them—do exist. On his way out of town, one of those Texas investors tells Carl’s father: “You know what you’ve done out here? You’ve turned your kids into the very things you left the city to escape from.” Right.