What is it about certain masterful forms of puppetry that causes artificial beings to become lifelike? It has less to do with the performer’s voice than it does with how much can be conveyed nonverbally through the meticulously nuanced movement of the puppet itself. I’ll never forget how moved I was upon encountering an expertly built and performed Gonzo puppet back in the days when crowds were not a health risk. We spoke for several minutes, and not once did my eyes ever connect with those of the puppeteer. When we posed for a picture together, Gonzo put his arm around my shoulder, and the gesture felt so real that I nearly teared up. That is precisely the sort of palpable magic that theatre director Maleonn infuses into the full-bodied puppets he and his crew have created for their achingly personal show, “Papa’s Time Machine.” It was conceived as a way for Maleonn to fulfill the promise he made to his father, Ma Ke, a once-imposing director who oversaw over 80 productions at the Shanghai Opera House. He wishes to write a book about his career, but his memory has begun to flicker like a faulty bulb in a Lynch film.

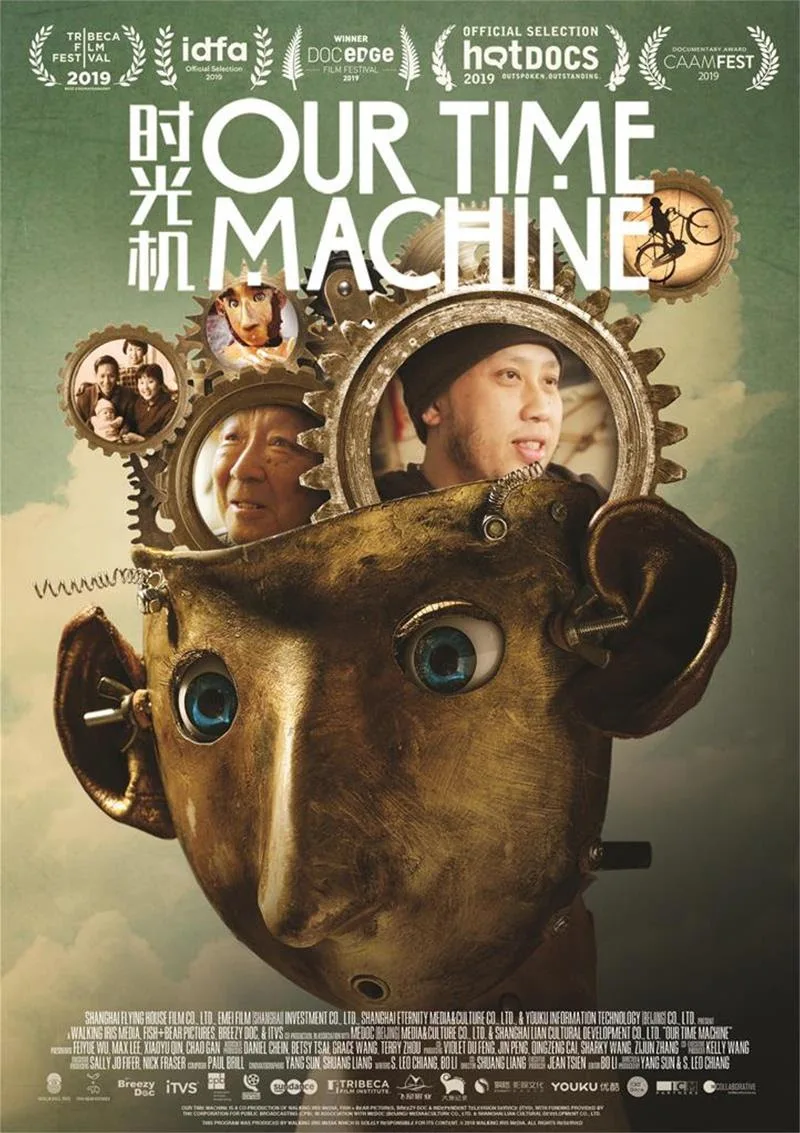

Though Maleonn doesn’t consider himself to be much of a theatre guy, he had wanted to immerse himself in that world in order to develop a closer bond with his father. As Ma Ke finds himself sliding into dementia, his son takes it upon himself to visualize their shared past onstage, a poignant project that forms the heart of S. Leo Chiang and Yang Sun’s documentary, “Our Time Machine.” It is not a film concerned with contriving satisfying payoffs, none of which are guaranteed when battling debilitating medical conditions that gradually rob the elderly of their identity. There is a lovely scene where Maleonn reminisces about how his father started talking to him like a fellow grown-up when he was 14, and though he can’t recall what they spoke of, he vividly remembers how he felt. His puppets brilliantly externalize how our minds reconstruct remembered events as abstractions based not in specific details but heightened emotion. Their ingeniously designed wires and gears represent nothing less than the mechanics of memory which, like all mortal faculties, have an expiration date. Amidst his repetitive rants about all he’s striving to remember, Ma Ke finally takes a moment to laugh helplessly at the futility of his effort, observing, “The machine is broken.”

According to their director’s statement, Chiang and Sun were drawn to the material in part because Maleonn’s attempt to connect with his father reflects his generation’s desire to preserve the sense of history and tradition that the Cultural Revolution threatened to erase. When Ma Ke visits his sister’s house for the first time in two decades, he’s able to grasp onto fragments of his past, such as what it felt like to be a mere child during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Like many artists, Maleonn’s parents were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, resulting in them being forced to farm cotton, though they were just glad to still be alive. No attempts are made to sugarcoat the harrowing daily reality for this devoted couple, and there is frank scene where Maleonn’s mother tearfully confronts her son about how families should share the burden of caregiving that has fallen on her shoulders. Though Maleonn has no intention of having them wind up in a nursing home, he’s uncertain whether his play will ever generate the amount of income needed for him to purchase a house where they could all live together. It’s heartbreaking to watch the 40-something bachelor, so full of infectious life when in the throes of creative discovery, fall into despair when faced with his lack of options. Helping his parents would mean halting the completion of a show designed to bring beauty to audiences, and Maleonn—at his lowest point—surmises that the world doesn’t deserve beauty.

The prize-winning cinematography by Sun and Shuang Liang accentuates the film’s overarching interest in visual poetry as opposed to exhaustive context. Maleonn’s playful yet haunting approach to surrealist photography is clear from the get-go, as the movie surveys his shadow puppets evocative of those devised by Manual Cinema for Nia DaCosta’s stunning “Candyman” teaser, another potent though far more scarring portrayal of painful memories. The ability to animate what would normally remain inanimate has fascinated Maleonn ever since his father introduced him to the fairy tale of Pinocchio. His characters are entrancing because they move as a human would, not unlike the stop-motion marvels in “Anomalisa” or the Gelfling in “The Dark Crystal.” Maleonn is also wise to have his characters speak in puppet dialect, knowing fully well that such beings—when properly operated—have no need for dialogue to convey their inner thoughts. In fact, my biggest gripe with the movie is that it doesn’t provide us with nearly enough footage of the play itself, which is fed to us only through fleeting snippets that are so transfixing, they made me want to seek out the full production immediately (here’s hoping that footage exists). Many other aspects of the nonfiction narrative are left frustratingly murky, such as how the show was able to eventually raise the crucial funds in order to have a limited run, or what led romance to blossom between Maleonn and his show’s assistant director, Tianyi.

“Our Time Machine” leaves you wanting a whole lot more, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. If cinema can be interpreted as yet another variation on H.G. Wells’ time machine, then Chiang and Sun have succeeded at transporting us into the psyches of their subjects, where past events blur together with our impressions of them. Bookending the picture are letters written by a father to his child that illuminate the circular nature of the story, and of life itself. In its final moments, Maleonn has become a father who has learned to savor reintroducing his daughter to his own dad, because it means that Ma Ke can re-experience the joyous news again and again. As Proust wrote, “We do not succeed in changing things in accordance with our desires, but gradually our desires change.” The show may not have had its intended effect, yet it still managed to fulfill a wish long held by its creator. The true joy, of course, is in the doing rather than the end result. To Maleonn, creating art isn’t all that different from falling in love. It may be utterly irrational, but we have no choice other than to do it.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.