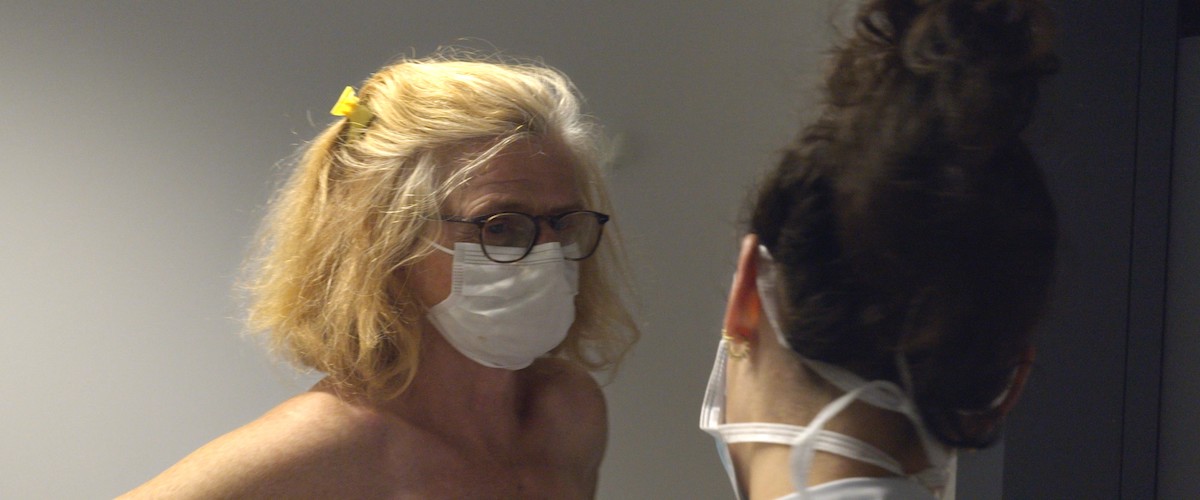

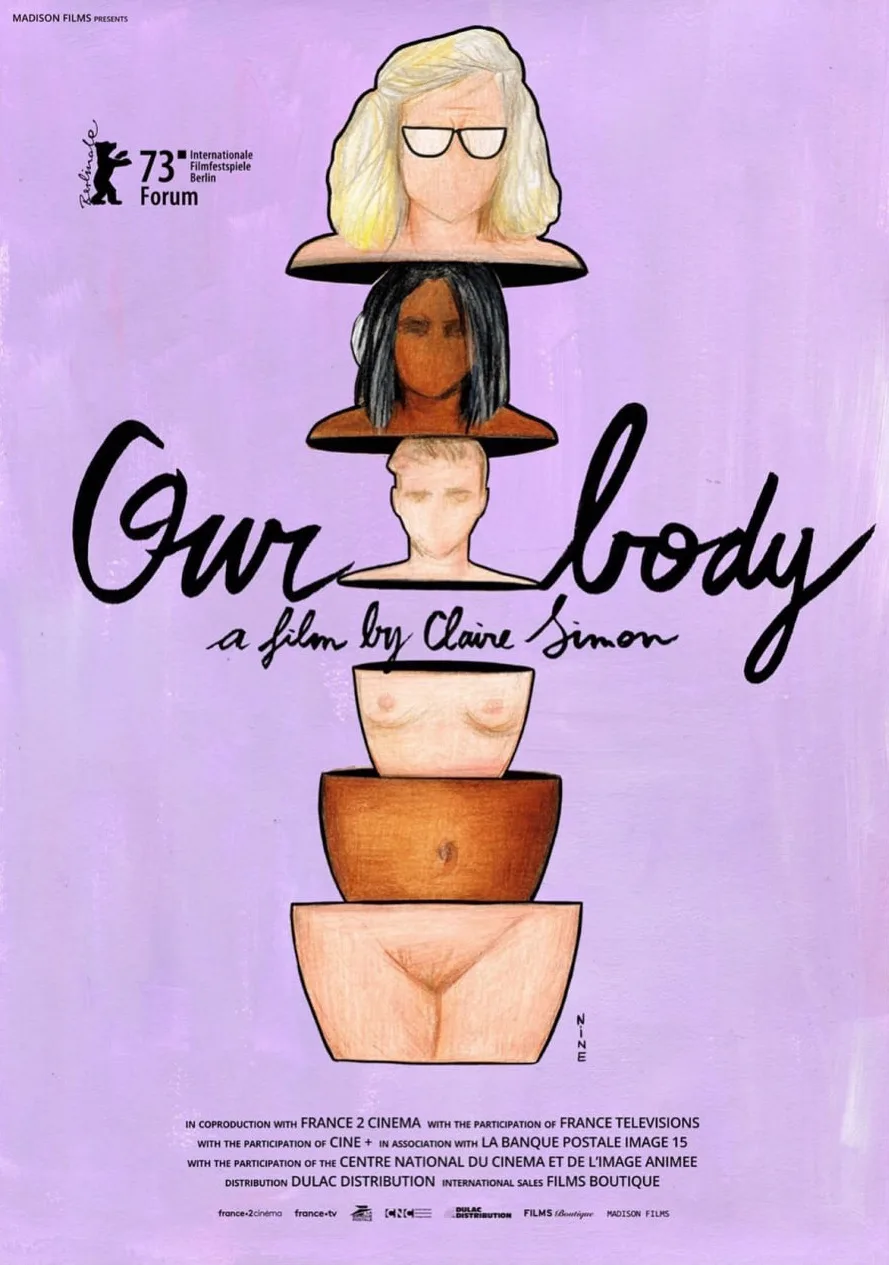

French documentary director Claire Simon appears just a little over three times in “Our Body.” At the beginning, we see her walking from her home to the hospital, past, as she points out, the cemetery where her father was cremated. She tells us the idea for the movie came from one of her producers. There was “an encounter.” Her producer had an illness “that brought her into a female world.” And so Simon and her camera entered that world of “gynecological pathologies that weigh down our lives, our hopes, our desires.” She jokes darkly that she hopes she will not catch cancer there.

And then in a Frederick Wiseman “fly-on-the-wall”-style film, Simon takes us into the most intimate, terrifying, and sometimes joyful moments faced by the people who come to the hospital. But unlike Wiseman, whose films focus on institutions and bureaucracy, the focus here is on the lives of the patients and their interactions with very patient, sympathetic, and capable health care professionals. We see very little of the lives of those professionals. There are only two scenes without any patients. One is a very businesslike clinical discussion of care plans and prognoses. The other is a truly astonishing scene of doctors in a lab, carefully joining an egg and sperm for a couple who need help getting pregnant.

Even with an almost three-hour run time, this is not the kind of film where experts weigh in with facts about health care policy or particular diseases or treatments. And it is not the kind of film where we see what happens to the patients we observe with their caregivers. Every scene is just a tile in the mosaic, not a part of a linear storyline arc. Very occasionally, we hear Simon ask a question off camera, and sometimes there is a light trickle of music on the soundtrack. But most of the film is quiet conversation, punctuated only by the hospital sounds echoing in the hallways and examination rooms.

Americans will be especially interested to see that patients never feel rushed. No one worries about insurance or Medicaid or filling out forms or not being able to pay for care. While all the caregivers we see are compassionate and professional, at one point there is a protest rally outside the hospital, with angry patients complaining about abuse.

Inside, a teenage girl wants to terminate her pregnancy. A pregnant woman with cancer wants to be able to deliver her baby. Operation scenes (sometimes graphic) show us how the medical professionals work as a team. A trans man has to wait 11 months, until he is 18, to consent to the medical treatment his father will not approve. Doctors find a way to communicate with patients who have difficulty understanding the implications of their medical issues and evaluating the options they have to consider. Some of them are not native French speakers. In one case, they pass an iPhone back and forth to translate. An older trans woman learns she has to go through her own version of menopause. It is time to stop taking the estrogen that has been a foundation of her transition. A doctor points to the places in his own body to help the patient understand. Another doctor uses words that are gentle but vague. “Sometimes the disease can defeat bravery and defeat medicine.” Her words may not be clear but the way she grasps the patient’s hand tells her and us what she means.

We notice those hands because Simon has an exceptional eye for the small details that illuminate the quiet but devastating, literal life and death moments. In another scene a slight widening of a close-up subtly reveals a wig removed from a patient receiving chemotherapy. We also see a woman giving birth attended by just one medical professional, who gently coaxes and encourages her. The father is at home, caring for their other children. There is that moment of pure magic when suddenly a baby is welcomed to the world and the very first words she hears are her mother’s whispers of hope, love, and joy. There are people who hear bad news and people who are learning what their lives will be after debilitating and sometimes disfiguring treatment. There are people who need medical assistance to become pregnant and some who learn that they will never carry a child.

The patients are very diverse (except that none of them are wealthy; apparently the rich have other sources of health care). The medical staff are all kind and thoughtful. The film would have benefitted from more about their perspective, how they manage the stress of the job.

Simon tells us at the end that the doctors have many stories, but the patients have just one. Those stories together create what she calls “a crazed waltz of destinies.” And as Simon finds herself on the other side of the camera, hearing her own results from a doctor, it underscores the movie’s most important message that we all dance in the crazed waltz some day.