See if you can follow this. An inner-city high school in Miami is descending into anarchy. The students have open disrespect for the teachers. A gang of drug pushers and chop shoppers run things. Then Louis (Mark Dacascos), a former student of the school, returns after serving for four years in the U.S. Army in South America, and proposes to change things. His plan? He will scrape the bottom of the barrel, taking the 12 most troublesome students, and reform them by teaching them martial arts.

His plans go well. He restores an old firehouse and holds classes, where the dirty dozen, of course, turn into martial arts virtuosos and at the same time are transformed into well-behaved citizens, with the slight flaw that they now move and think as a monolithic unit. They go on field trips to beaches and the Everglades (and apparently not to any academic classes), while the school’s principal vows that the program should be extended to every other school in town.

The local vice lord is not, of course, made happy by the changed situation, confronts the martial arts teacher and vandalizes the school. The principal insanely blames the damage on Louis the teacher, and has him escorted from the school under police guard.

Then Louis and his followers declare war, and we witness a series of martial arts battles leading, of course, to the ruin of the bad guys.

I have a sinking feeling that the makers of this film feel it is in some way exemplary and even useful. But consider the lessons it teaches: (1) School is irrelevant compared with the mastery of the martial arts; (2) if 12 troublesome students are removed from classes and set up in a separate program, the remaining students somehow magically will also be transformed; (3) the answer to violence is greater violence, and (4) self-respect and self-esteem, those qualities notoriously lacking in the opening scenes of movies like this, can quickly be gained through adherence to a gang. (Simply because the gang is a “good” gang and called a “program” does not change the fact that the students are under the command of a leader, and use violence to set things right.) Watching the film, my mind went back to “Stand and Deliver” (1988) and “Lean on Me” (1989), two other movies where strong teachers tried to turn around anarchic school situations. Both films had their problems, I thought, but they did cherish the quaint notion that students will never be able to exercise meaningful power in society without learning to effectively read, write and deal with numbers. Anything else is a lie. Kick boxing may be a useful skill, and I can see in this movie that it’s an exciting sport. But it is not something you can count on to support a family in your later years.

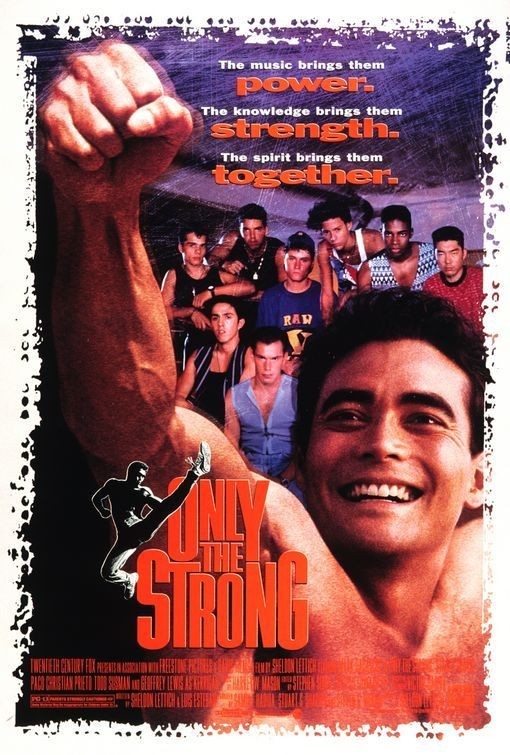

Seen simply as a sports film, “Only the Strong” does have its qualities. Dacascos and the other leads are impressive athletes, and their grace and strength are well choreographed and photographed here. Martial arts fans will probably enjoy the film.

Fans of logic, however, may ask themselves such questions as: (1) What happens if people decide to shoot you instead of following the conventions of martial arts? (2) How can you convince the bad guys to come at you one at a time, instead of all together? And (3), exactly how and why, when someone is menacing you, does it help to do a back flip? God knows, a lot of American schools are in terrible shape.

But I am not sure “lack of self-esteem” is the greatest problem, in the student bodies, and I am convinced that you do not become somebody simply by saying “I am somebody” (those three words, indeed, strike me as counterproductive, because they send such a sad message about anybody who would need to say them).

Until we decide to spend the money to support better teaching and smaller classes, and until we deal frankly with the problems of guns, drugs and poverty that are reshaping American schools, the problems will get worse, not better.

The message of a movie like “Only the Strong,” building on the fascist undertones of its title, is almost cruel in its stupidity and naivete. It’s almost a relief that few people in the audience for such a film ever remember if it even had a message or not.