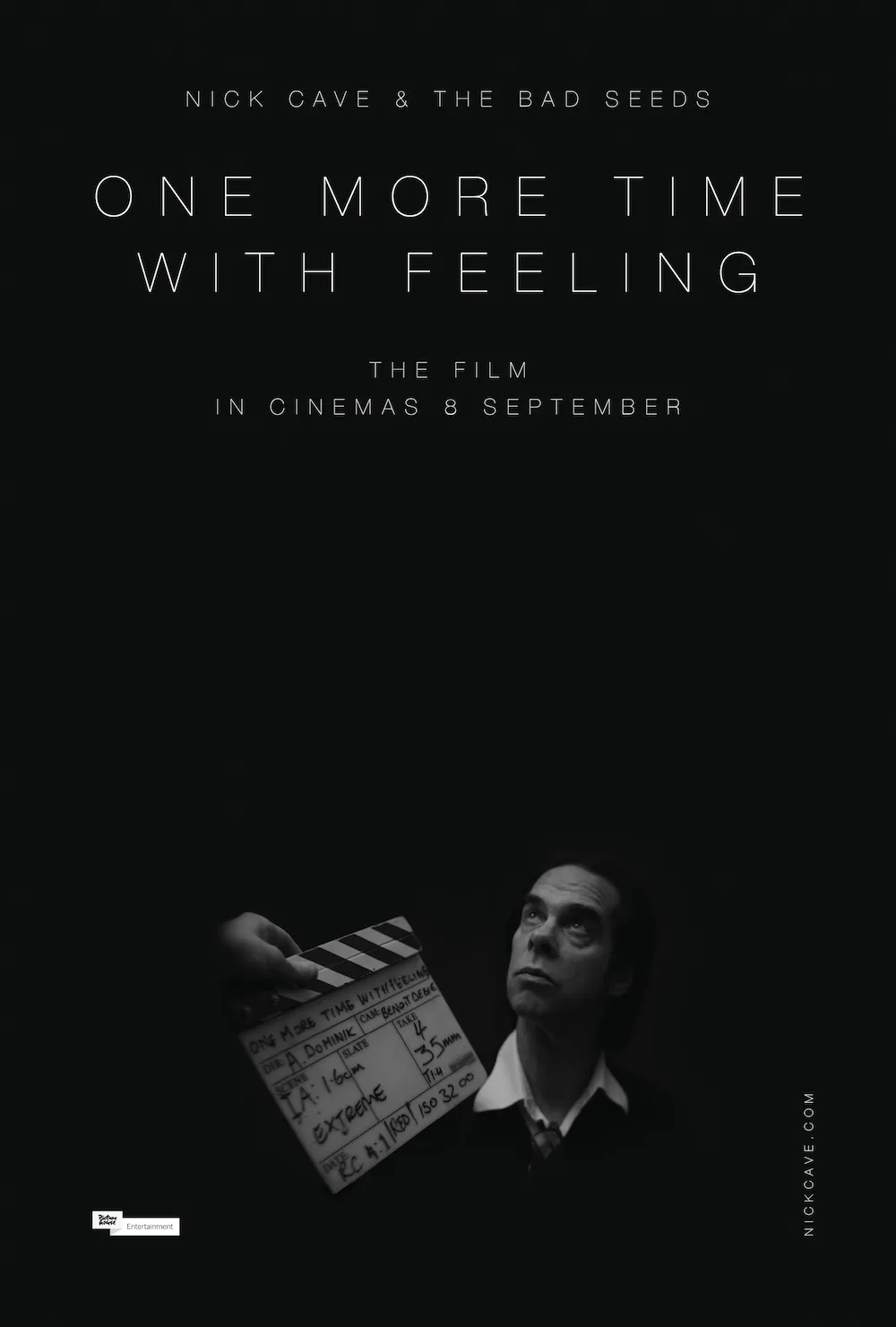

When you start watching “One More Time with Feeling,” you are suddenly dropped into the eye of a creative storm that began after the death of Arthur Cave, one of Australian rocker Nick Cave’s two sons. This deeply moving concert doc concerns that loss, but only indirectly. We join Cave before the release of Skeleton Tree, his latest album with decades-old band The Bad Seeds. But by the time director Andrew Dominik films Cave (using a 2D camera and an advanced black-and-white 3D camera) and his band in their Brighton recording studio, it seems as if the bulk of Cave and his band’s creative decisions have been made. Still, anxiety permeates the studio: how will people receive Skeleton Tree, a characteristically intimate, but highly conceptual album that only addresses personal loss in the abstract?

Dominik (director of “Killing Them Softly,” “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford“) tries to preserve Cave’s uncertainty by presenting Cave’s studio recordings as a mix of polished concert footage and off-the-cuff interview footage that reveals Cave’s tortured headspace. Cave tells Dominik that Arthur’s death has obstructed his creative process by making him feel adrift. Dominik tries to illustrate the “elastic” interminable present moment that Cave is experiencing by conflating time and space during recording sessions.

“One More Time with Feeling” is a uniquely cinematic documentary, one that actively blurs the line between fact and fiction. Sometimes Dominik’s 3D camera drifts through solid surfaces, including people, doors and walls. Sometimes it snakes around Cave while 2D videographers film Dominik at work. Once or twice, voiceover narration of Cave’s innermost thoughts—recorded after the events filmed—give us a hyper-real window into his thought process. This isn’t really a movie about creativity, though it is that, after a fashion. Instead, this is a movie about the pause before the end of a creative obstacle. We join Cave moments just after he’s decided to continue struggling without his son. Arthur’s death still weighs on him, as it would any parent. But Skeleton Tree is now out in the world, and cannot be contained by Cave’s subconscious.

I hesitate to credit Cave’s subconscious with having done the heavy-lifting on Skeleton Tree since he himself seems unsure from where his newest album’s songs came. He talks about “Gods” and “accidents,” and repeatedly talks about God and his bandmates in the same breath. Like the late Leonard Cohen’s music—an acknowledged influence on Cave’s style—Cave seeks answers to spiritual questions for which he suspects he already knows the answers. He is his own God because he is, as he tells Dominik when he reads lyrics to as-yet-unreleased songs, different than the universe since he has “consciousness.” Cave’s art is a struggle to paradoxically honor and resist his consciousness’ need to make sense of the world. When Dominik asks why Cave’s recent music isn’t driven by narratives, the musician responds, “Real life isn’t like that.” But art can be, Dominik argues, by creating a beautifully unhinged snapshot of Cave just after he experiences a major personal loss and a minor creative epiphany.

Dominik’s film owes a great deal to experimental filmmaking techniques that Jean-Luc Godard used in the Rolling Stones not-quite-doc “Sympathy for the Devil” and avant garde musical “A Woman is a Woman.” In those films, Godard constantly deconstructs the narratives he employs as a means of provocatively suggesting that language can only fitfully express truly profound meaning/revolutionary thoughts/sublime joy. Dominik’s film is similarly about Cave’s need to express himself without sounding trite or platitudinous. He does not want to escape from Arthur’s death, but he also hesitantly tells Dominik, during incisive interview footage, that he doesn’t want to commemorate his son through sentimental truisms, like “he lives in our hearts,” a saying he spits out because “[Arthur] doesn’t live at all.”

Cave adds that he chooses his words very carefully because he doesn’t want to be trapped by the brittle images that his words directly conjure. Dominik responds in kind by filming himself struggling—and often succeeding—at giving dimension and shape to Cave’s grief. Nothing can give shape or closure to Cave—and that’s OK. Watching him continue his ongoing search for existential answers is comfort enough.