A rainy afternoon in a fern-carpeted Cascade forest. A black slug slides across a boulder cusioned with brilliant green moss. Why do I think I’ll remember that moment from Kelly Reichart’s “Old Joy” for a long, long time? It doesn’t have anything to do with furthering the story, about two old friends who haven’t seen each other for a while and take an overnight trip to a hot springs in the mountains near Portland, Oregon. It’s just… right. The right image in the right place at the right time. Necessary. Essential.

Like a great jazz musician, Reichart understands that striking a single, well-placed note can resonate more profoundly than playing a splashy cascade of noise just because you can. “Old Joy” resounds with sustained images and sounds that are given the time and space to reverberate — fitting for a movie that begins with the chirp of a bird perched on a gutter and the chime of a meditation gong.

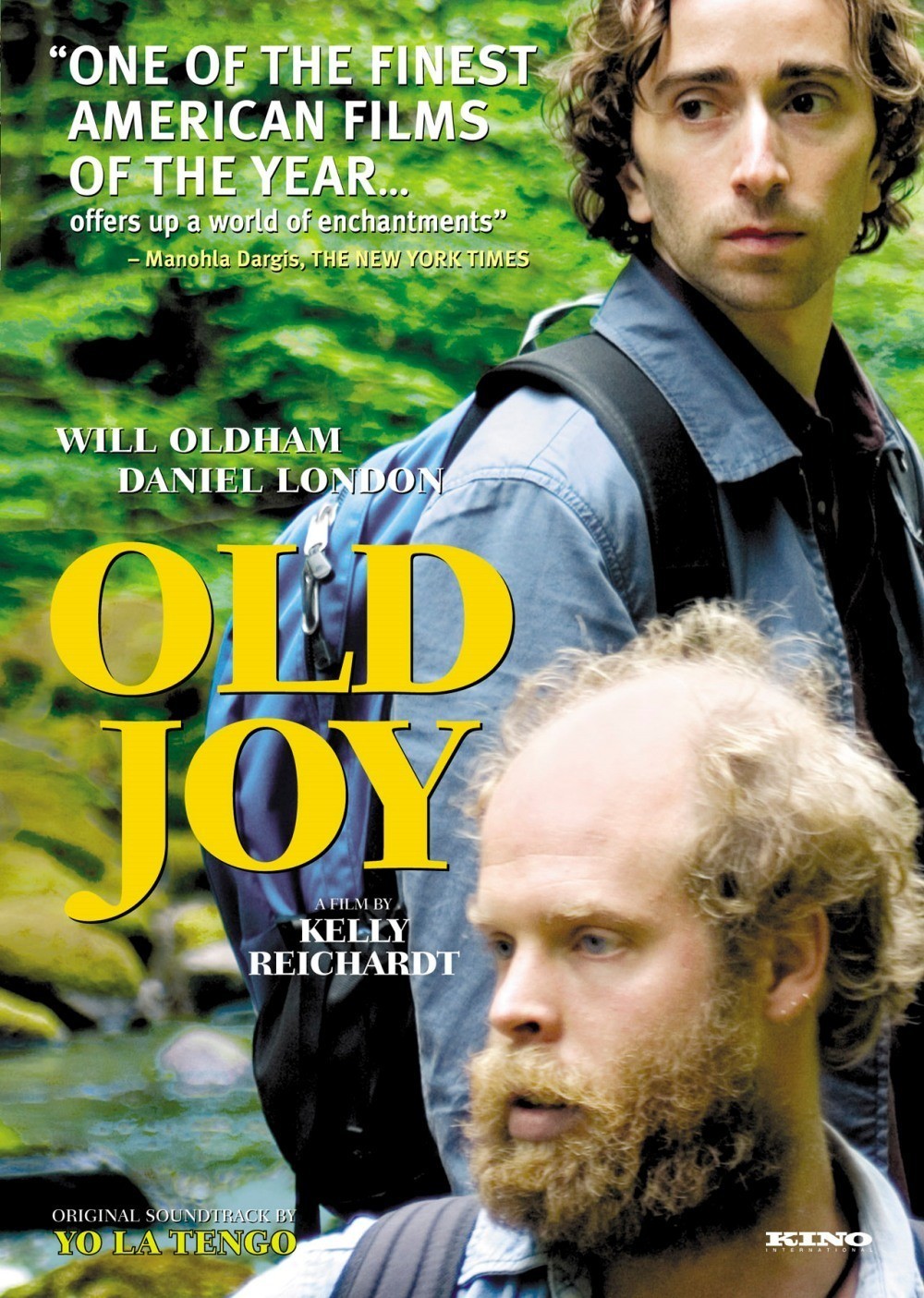

It’s based on a short story (and feels very much like that atmospheric, economical form of storytelling) that comes down to this: The two friends, Mark (Daniel London) and Kurt (Will Oldham), drive up into the mountains and get lost trying to find the hot springs. They pitch camp at a spot littered with abandoned furniture and spend the evening drinking beer around a fire and shooting at the cans with a pellet gun. The next day, they find the springs. After soaking in them for a while, they drive back to Portland.

The End.

Of course, that is no more an accurate description of “Old Joy” than saying James Joyce’s The Dead is about some Irish people who go to a party and then go home; meanwhile, it snows. It’s not only that innumerable incidents are left out of this outline, but that what happens in the story isn’t defined by incident. In that sense, I couldn’t synopsize what happens in “Old Joy” any more than I could tell you what happens in “The Dead,” or Yasujiro Ozu’s “Late Spring“, or Miles Davis’ “In a Silent Way.” Everything happens. But, as they say about jazz, it’s as much about the notes you don’t play (but hear nevertheless) as the ones you do. And sometimes the greatest drama can take place between the lines, or outside the province of the frame, and all we notice is a pause or a glance. Or a shot of a slug moving across some moss.

Some may think of it as “leisurely” or “slow-paced,” but those but those qualities contribute to the almost unbearable suspensefulness of “Old Joy.” There are unarticulated tensions, feelings of sorrow, unease and even dread that course through the movie like a hidden creek. And when Mark and Kurt finally locate the turn-off to the springs, we see the sky reflected in their windshield and the whole world turns on this moment. What is about to happen? Will we recognize it when it does? Or did it already happen? What did it mean? “Old Joy” is not going to offer up its secrets — mysteries of the human heart and mind — in a glib or facile manner. All you have to do is watch, and feel, and think.

Kurt obviously yearns to reconnect with Mark, and with the past, in some way, and he’s saddened and frustrated that he can’t. Mark, who drives around listening to Air America as if it were the one thin remaining tether to a larger dynamic world of politics and idealism that he used to believe in, seems perpetually numb. Part of it’s political — living in a blue state (in every sense), depressed into a condition of learned helplessness by elections and events, while the impotent callers on the radio drone about the possibility of a third party and bemoan the nonexistence of a second party. But perhaps the third party weighing most heavily on Mark’s mind is the one in the belly of his wife, Tanya. He’s about to become a father.

Kurt (and it’s OK to make the connection to another young blond man named Kurt from the Pacific Northwest) thinks of himself as a spiritual seeker, but that may be because he still smokes way more dope than any of his old friends, most of whom he’s lost contact with. In one of the movie’s best sly jokes — and most telling bits of characterization — he slips on a pair of plum-colored shorts, and his purplish wardrobe looks like cast-offs from the early-1980s Oregon ashram of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, followers of whom, Pacific Northwesterners recall, always dressed in those colors favored by their guru, who was deported from the United States for immigration fraud.

The way Kurt spins his stories, he’s always going off on wilderness enlightenment retreats, and has just returned from Ashland, which he says was “amazing. Tranformative. I’m at a whole new place now, really.” Both Kurt and Mark behave as if they’d had this same conversation a million times before. Kurt is a flake — the kind of guy who sleeps on friends’ couches well into his 30s or 40s — but he’s also troubled by his inability to adapt to adulthood.

What does Kurt want from Mark? Is it lost brotherhood, agape; or is there a sexual component, or does he just wish Mark could give him back the old days, and old joys, of their younger selves? Those questions, which linger long after the movie is over, make “Old Joy” unshakable.