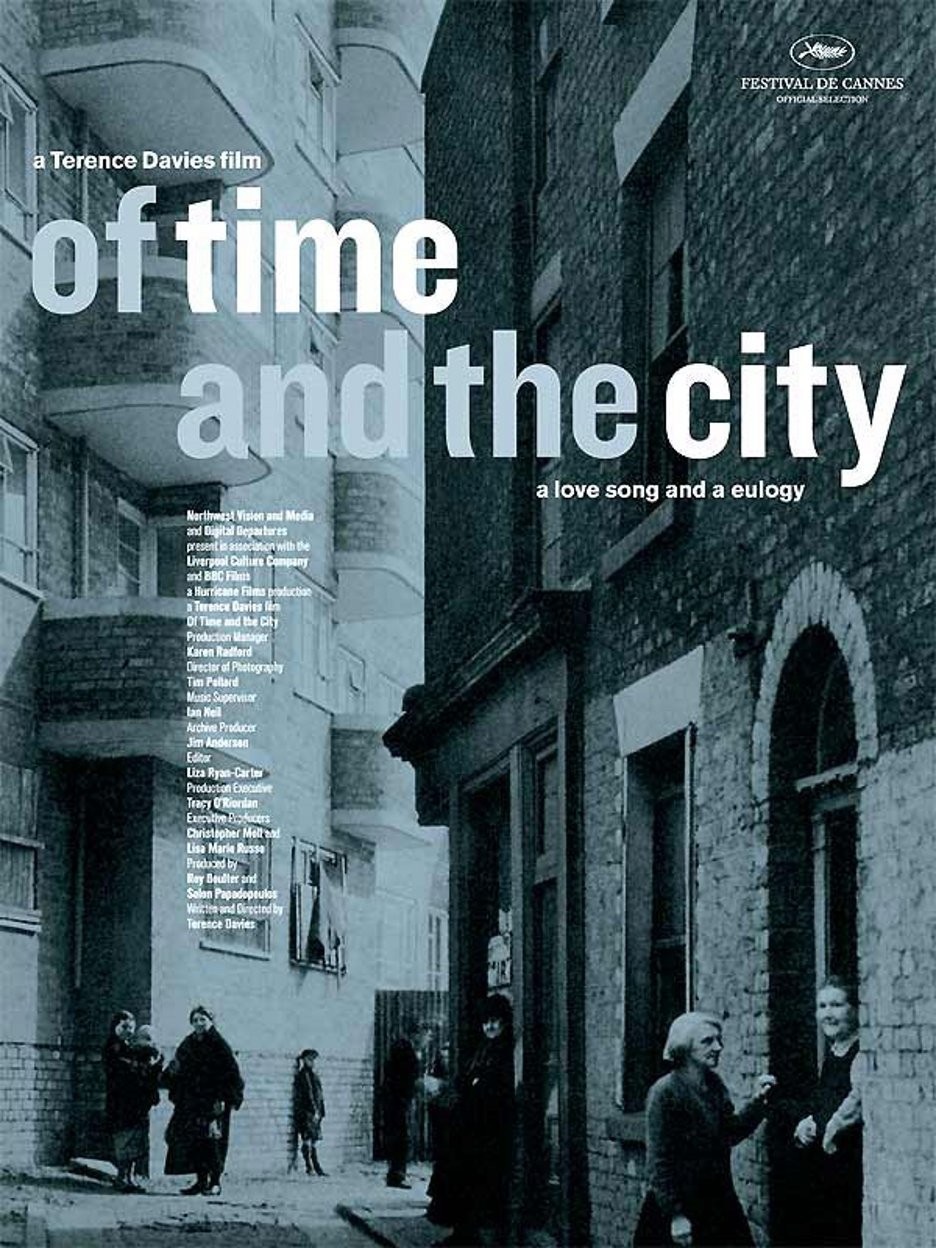

The streets of our cities are haunted by the ghosts of those who were young here long ago. In memory we recall our own past happiness and pain. Terence Davies, whose subject has often been his own life, now turns to his city, Liverpool, England, and regrets not so much the joys of his youth as those he did not have. Central to these are the sexual experiences forbidden by the Catholic Church to which he was most devoted.

Liverpool was once a shipbuilding capital of the world, later a city broken by unemployment and crime, and now a recovering city named the European Capital of Culture in 2008. For many people, Liverpool’s cultural contribution begins and ends with the Beatles, and Davies does little to update that view, except to focus on its postwar architecture, which is grotesque, and its modern architecture, much improved, but still lacking the grandeur of the city’s Victorian glory.

The way Davies and cinematographer Tim Pollard regard heritage buildings and churches, their domes and turrets worthy of an empire, suggests that he, like me, prefers buildings that express a human fantasy and not an abstract idea. What is it that makes the Hancock magnificent and Trump Tower appalling? Not just the Trump’s bright shiny tin appearance, the busy proportions of its facade or its see-through parking levels, but a lack of modesty and confidence. It insists too much. However, there is nothing modest about the grandiloquent civic structures of Liverpool, but their ornate cheekiness is sort of touching. They had no idea that they were monuments to the end of an era.

In this city Davies was born into modest circumstances, was shaped and defined by the church, was tortured by his forbidden homosexual feelings, gradually grew to reject the church and the British monarchy. He remembers a boy who put a hand on his shoulder “and I didn’t want him to take it away.” In his parish Church of the Sacred Heart, “I prayed until my knees bled,” but release never came.

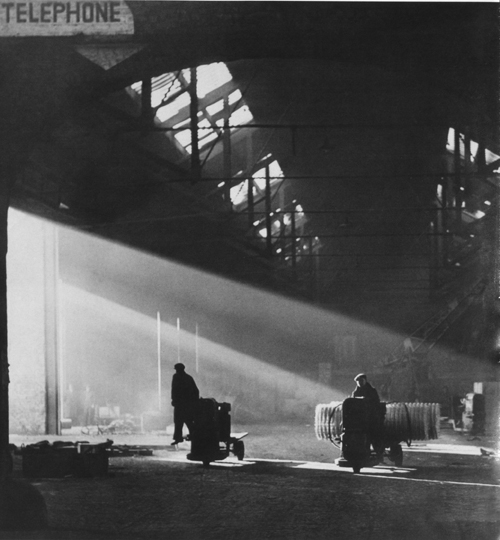

These memories are mixed with those of the city, suggested with remarkable archival footage collated from a century: crowds in the streets and at the beach, factories, shipyards, faces, movie theaters, snatches of song, long-gone voices, an evocation of a city tuned in to the BBC for the Grand National, a long-gone horse and rider falling at the first hurdle, the wastelands surrounding new public housing, children and dogs at play and yes, the Beatles.

The soundtrack includes classical music and pop tunes, and the deep, rich voice of Davies, sometimes quoting poems that match the images. The film invites a reverie. It inspired thoughts of the transience of life. It reminded me sharply of Guy Maddin’s “My Winnipeg” (2008), which combines old footage and new footage that looks even older into the portrait of a city that existed only in his imagination. I imagine the city fathers in both places were astonished by what their sons had wrought, although in Winnipeg, they would have found a great deal more to amuse them.