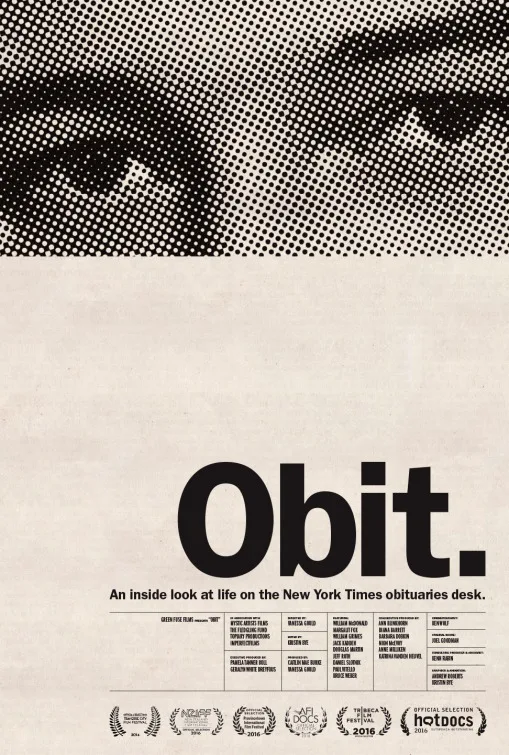

The fascinations of “Obit,” Vanessa Gould’s slick but entertaining documentary about the New York Times obituary department, operate on two levels. On the more superficial level, readers of the Times are bound to enjoy an inside look at one of the paper’s most dependably enthralling sections, a compendium of pithy, authoritative overviews of recently ended lives.

At a deeper level, no interest in the Times—or any other newspaper or online obituary source, for that matter—is necessary to engage viewers with certain questions the film inevitably suggests. In what light will death cast my own life? Will it look more good than bad, or vice versa? What will people think and say about me once I’m gone? What will the public record show? Will I rate a Times obit, that veritable Oscar of the afterlife, or simply fade into post-mortem oblivion?

Deeper philosophical, spiritual and psychological questions along these lines are seldom broached in “Obit,” but they percolate just beneath the surface throughout. That surface offers a brisk, informative tour of the obituary department in operation, watching its staff meetings and listening to Times writers (most of the film is interviews with single subjects facing the camera) reflecting on the decisions, working methods and implied values that go into their daily chores.

One point that should be made early in any review, as it is in the film, is that nothing here deserves to be characterized as morbid. Indeed, quite the opposite: Times obits deal with life, not death. And while sadness and tragedy provide the dark borders around some lives, obituaries’ natural emphases fall on notable accomplishments, significant impacts on history or culture, or the quirky traits that make an individual personality stand out.

A narrative line that runs through the film follows veteran obit writer Bruce Weber as he assembles an obituary for William P. Wilson, who served as a media consultant to John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential campaign. Weber goes about his work methodically, sitting at his computer in the obituary newsroom, looking through files, going over facts with Wilson’s widow on his headset.

This choice of subject is shrewd on the filmmaker’s part, of course. Not only does it remind us of what may be counted the most shocking and significant obituary of the last century; it also gives us the living JFK at his most composed, confident and handsome, via documentary footage that brings to life the fateful intersection of politics, mass media and advertising in the “Mad Men” era.

There they are again, preparing for the TV debate that will edge Kennedy in the lead: JFK looking sleek and pristine, Nixon trying a little too hard to seem relaxed as his five o’clock shadow begins becomes visible. One of Wilson’s contributions to this event, we learn, was having the candidates stand behind thin-stemmed lecterns, which gave a subtle advantage to the more poised and at-home-in-his-own-skin JFK.

Such peeks into the little-known byways of history are part of what make many obituaries enthralling. And they also explain why the writers interviewed here seem to approach their tasks with undisguised pleasure as well as professional commitment.

One thing the film points up is how often Times obits are devoted to history’s bit players, such as William Wilson. Such stories usually require some delving and research. For the very famous, much of the work has been done in advance and is on file. But then there are times like the day when Michael Jackson died unexpectedly and the obituary department had to go into manic overdrive to deliver a story by deadline.

A notable subgenre within the documentary form involves showing people at work, doing jobs high and low. Such films almost always reward attention because they have innate narrative lines and human interest. Since most of us work, who doesn’t enjoy seeing a job both performed and examined? In “Obit,” we hear numerous lives discussed or referred to, and pictures—some drawn from the Times’ famous morgue—recall the looks of the deceased. There are also montages of old newsreels that provide quick glimpses of countless people at work and play during the last century, footage that recalls Jean Cocteau’s famous remark that cinema is the only art that “shows death at work.” In “Obit,” that process ends up being the work of a group of newspaper professionals who show a commendable dedication to both facts and meaning. Which is no small virtue at a time when both seem under siege.