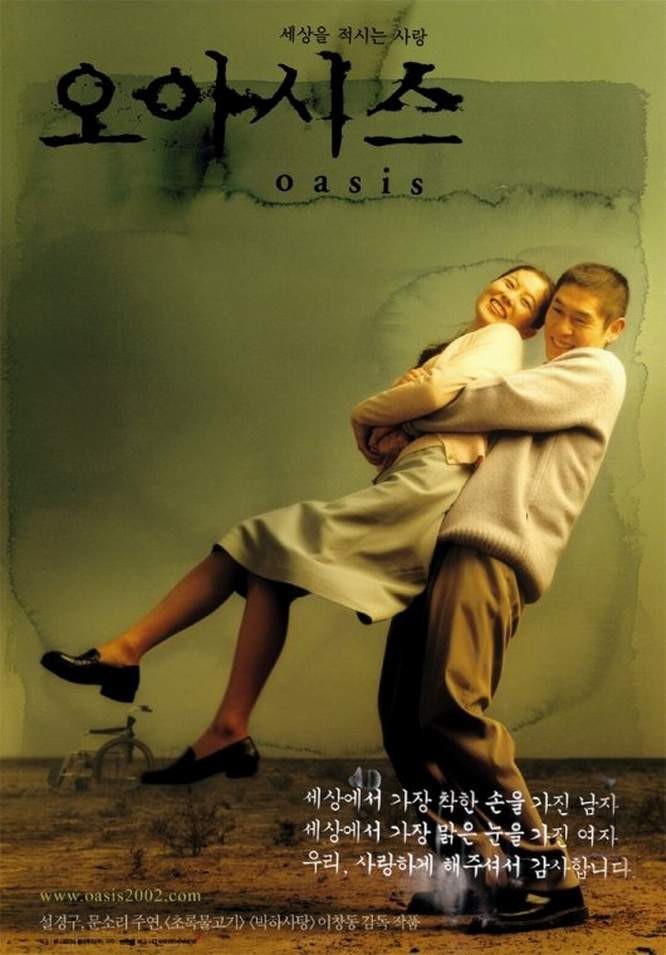

“Oasis” is a love story involving two young people abandoned by families unwilling to give them the love and attention they require. We in the audience may be equally unwilling to give them love and attention, and that’s why the film works so powerfully. Its heroine is a woman rendered almost powerless by cerebral palsy. Its hero is a man so obnoxious and clueless that while he’s in prison his family moves and leaves no forwarding address. They meet when he rapes her.

The new South Korean cinema is transgressive and disturbing, open to forms of behavior that are almost never seen in the films of the West. It can be about urgent, undisciplined, perverse needs; it can have the graphic detail of pornography yet show no hint of an erotic purpose; it can accept extreme characters and make no attempt to soften them or make them likable. There’s something stunning and even inspiring in its indifference to popular taste. “Oasis” depends on scenes that could not be contemplated within the Western commercial cinema; it is unconventional to the point of aggression.

The movie opens with Jong-du Hong (Kyung-gu Sol), newly released from prison, seeking out his younger brother. He needs help because, in his passive-aggressive way, he has ordered food in a restaurant without being able to afford it (no, they don’t want to accept his shoes as payment). Jong-du is one of those people the rest of us instinctively avoid. He looks at people strangely, asks inappropriate questions, assumes an unwanted intimacy, violates their space, doesn’t know the rules of social interaction, and in general inspires his targets to make a perfunctory and inane response and get away as quickly as possible. He may be retarded, but the movie doesn’t make that judgment; perhaps he is intelligent enough, but socially dysfunctional.

Jong-du has just served time for a hit-and-run episode. He has no money and no job prospects, and his family would be happy to never see him again. One day he buys a fruit basket and goes to visit the family of the man he killed with his drunk driving. It is impossible to say why he thinks this gesture would be appropriate, and his manner is so odd that the dead man’s son and his wife are understandably enraged. But it is through this visit that Jong-du learns of the existence of the dead man’s daughter, Gong-Ju Han (So-ri Moon). Severely disabled, she remains in what was the family apartment; her brother and sister-in-law have moved out and have as little to do with her as possible. We gather she is cared for by a combination of sketchy social services and the kindness of neighbors.

Jong-Du returns to the apartment when Gong-Ju is alone, rapes her and leaves. He is amazed when, a few days later, he receives a message from her. He goes to see her, and they begin a romance that seems to meet their particular needs. For Jong-Du, who senses other people trying to shrink from him, Gong-Ju has the admirable quality of not being able to avoid him — or even, without immeasurable effort, arguing with him. For Gong-Ju, her new friend is a prize who provides sex, companionship, and a way to get out of the house. Their needs and motives come together, for example, when Jong-Du takes his new friend to dinner with his family; we (and they) are completely unable to read his motive. Is he being kind to her, standing up for what he believes in, or merely hoping to piss them off?

There are fantasy scenes when Gong-Ju seems miraculously restored, and can move with grace and speak with eloquence. I am not sure if these moments are poetic, or somehow cruel. I am reminded of a better film involving a similar character: Rolf de Heer’s “Dance Me to My Song” (1998), which starred and was written by the late Heather Rose, herself a victim of cerebral palsy. For her there was no possibility of fantasy scenes in which she danced about the screen, and her limitations became the movie’s greatest strength.

Still, “Oasis” is a brave film in the way it shows two people who find any relationship almost impossible, and yet find a way to make theirs work. The problems with the film come because it overstays its welcome. There’s a scene in which Gong-Ju’s family misinterprets something they witness, and their reaction leads to dire consequences which could surely have been avoided by a simple explanation. This is an Idiot Plot situation, in which the plot continues only because everyone acts stupidly. The closing scenes dissipate what has been accomplished, and seem not only unnecessary but harmful.

In the matter of romance between the disabled and the able-bodied, sentiment is usually the great weakness. A magnificent film like “Dance Me to my Song” was denied an American release because “The Theory of Flight” (1998, with Kenneth Branagh and Helena Bonham Carter) offered a more commercial, palatable treatment of a similar subject. Heather Rose’s film was frank and graphic. “Oasis” falls somewhere in between, with the twist that the able-bodied character is more incapable of dealing with everyday life than the CP victim.