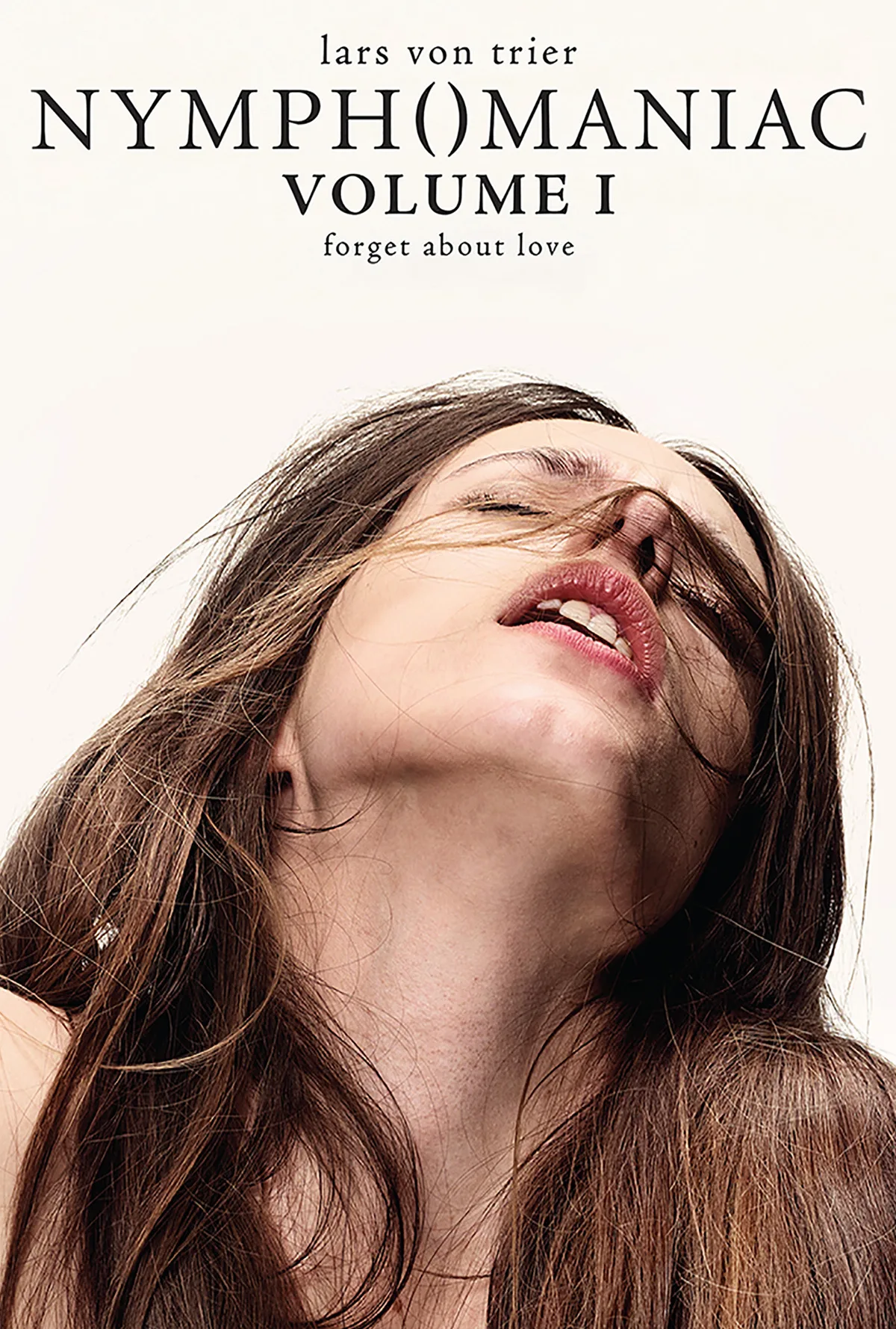

The first poster released for Lars von Trier’s “Nymphomaniac” had a Brady-Bunch structure, with images of all the main actors stacked on top of one another, each individual lost in the exact moment of sexual climax. The poster was eye-catching and funny, private and exhibitionistic at the same time. Sex may be “natural” and “good” (according to George Michael), but seeing sex onscreen (either actual or simulated) is often a game-changer. We all may do it, but how do you put it onscreen in a way that is representative of the mess/humor/actuality of it? How do you represent sex and also incorporate emotion? Human beings are often very silly about sex, especially when they get too philosophical about it. It’s like getting philosophical about a sneeze. Unlike a sneeze, sex carries lifetimes of associations with it, and yet naked writhing bodies onscreen often flatten out into a general cliche representing a hazy idea of the act. The best part of Lars von Trier’s fascinating, engaging and often didactic “Nymphomaniac” is that, despite the sometimes-grim tone and bleak color palate, it’s an extremely funny film, playful, even. It’s outrageous and provocative, intellectual and primal at sometimes the same time. It features of a lot of what looks like actual sex (although we are told in the end credits that the penetrative sex depicted was done by body doubles), and while it is obviously interested in sex, it is more interested in how we talk about sex, how we incorporate it into our identity (or don’t). Similar to “Melancholia,” von Trier’s masterful examination of depression, and how it feels like an outside force working on those who suffer from it, “Nymphomaniac” (which will be released in multiple volumes) sees sex through the eyes of a damaged woman who has made it her mission in life to remove sex from our “love-fixated society”. She says, flatly, “Love is blind. No, it’s worse. It distorts something. It’s something I never asked for.”

Charlotte Gainsbourg plays the androgynously named Joe, who, at the opening of Volume I, is discovered lying bruised and battered in a dark alley by Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård). Seligman takes her in, tucks her in bed, and gives her tea. He is a complete stranger and he asks what happened. She warns him up front that it will not be a nice story, that she is a bad person. He assures her that nothing she tells him will shock him. He thinks she may be being too hard on herself. There’s something almost unfinished about Joe, a flat affect, as she insists that her behavior has been beyond-the-pale. As the rain pours down, she tells him her story.

It’s a blatant theatrical device, an artificial framing, and von Trier uses it unabashedly.The film is broken up into titled-sections, each with their own narrative thru-line and tone. Occasionally, we go back to the bedroom with Seligman and Joe, when he interrupts her to ask a question about what she just said, or he interrupts to go off on his own tangent of thought. He is not freaked out by what Joe tells him. On the contrary, he is delighted by it, and seems delighted by the opportunity to talk about all of these important matters in an in-depth spit-balling kind of way. Seligman is a big fly-fisher, and much of what Joe describes, her various tactics with men, her use of different kinds of “lures”, reminds him of his favorite hobby.

Part of the delight in “Nymphomaniac” is its disinterest in being anything other than fully itself. That “self” may change on a moment-to-moment basis, which makes “Nymphomaniac” a dizzying experience. The film is sometimes stylized, other times totally realistic. Mathematical equations appear on the screen, counting out the sexual pumps from Joe’s first lover. There are intricate diagrams of a parallel parking job, showing the swooping parabolae necessary to fit a certain car into a certain spot. A chalkboard lists questions all starting with the letter “W”. There are long conversations about Edgar Allan Poe, Bach, and Fibonacci numbers. “Nymphomaniac” requires an audience to submit to these segues, to go with the flow, to hand over control.

In the flashback sections of Volume I, the young Joe is played by Stacy Martin, being raised by a “cold bitch” of a mother, and a kindly doctor father (Christian Slater) who passes on to his daughter a love of flora and fauna. She discovers early on that when she touches herself between her legs, she gets what she calls “the sensation”. Joe views her virginity as something that needs to be gotten rid of pronto, so she hits up a local rough-around-the-edges mechanic named Jerome (Shia LaBeouf) to do the deed; he complies with very little ceremony and no preamble. Jerome keeps entering the film, through various hard-to-believe coincidences. The mechanic somehow is transformed into a pencil-pushing office manager. When Jerome re-appears for the third time, Seligman, still listening, calls Joe on embellishing the story. This is sounding fictional now, cries Seligman. She must be making this up! Von Trier uses Brechtian distancing devices like that to comment on his own story, even as he meticulously sets up each self-contained section. He knows we’re going “in and out” of the action, he knows we’re going to have questions and doubt her reliability as a narrator. In fact, he counts on it.

Young Joe, once she lost her virginity, starts her quest to have as much sex as she possibly can. Her partner-in-crime for this is a young friend who is even more daring, and who comes up with various sexual competitions. They board a train and keep a running tally of how many conquests they can each make over the course of the night. Joe is amazed to discover how easy it is. She tells Seligman of her learning curve, the tactics and strategies she used as she worked that train. Every man is different. She is cold and calculating about it, and the scene really captures the restlessness and kamikaze bravery of young girls first trying out their sexual powers without knowing at all what they are doing. “Nymphomaniac” does not judge Young Joe and her friend. The only person judging Young Joe is the mature Joe, wrapped up in blankets, telling Seligman the story.

Every time Seligman interrupts, Joe reminds him that his feelings about her will change once he hears the whole story. It’s a hook, a tease, the film’s own fly-fishing “lure”. In one sequence, Joe relates the difficulties of juggling seven different lovers. Often the lovers meet at her door, one guy leaving as the other guy arrives. Things get messy. Joe may be able to separate sex from emotion (as a matter of fact, that is her goal), but it is not as easy for others. One guy shows up at her door, holding a couple of suits in dry-cleaning bags, announcing he has finally left his wife and is moving in. Joe is horrified, even more so when the scorned wife, known only as Mrs. H. (Uma Thurman, whose manic vicious performance is one of the film’s high points and tips “Nymphomaniac” over into out-and-out screwball) shows up at the door with her three children. She wants the boys to see where Daddy has been spending all his time. “Come, boys, let’s go look at the whoring bed!” exclaims Mrs. H. brightly.

The American actors use on-again off-again British accents, which adds to the blasé humor of the thing. It’s not important where these people are. It’s not even important who they are. It’s important what they do, and it’s important how they think about what they do. “Nymphomaniac” does not make the mistake of suggesting that Joe’s behavior is connected to a bad experience in her childhood. This is not a redemption narrative or a trauma narrative, at least not yet. Sex feels good all on its own; sex is its own reward.

Seligman sometimes misses the point of Joe’s narrative, musing about how addiction can dull a person’s moral apparatus. Joe wants to make sure she is perfectly clear with him: She embraced sex because of the “sensation” it provided her. The power she had over men was secondary. She loves lust, and her lust makes her heartless. Well, it’s a heartless world. Joe sees herself as an outlaw, taking charge of her own hunger, and as a young woman she and her group of fellow outlaw friends create a club which has an Erica Jong-like mission statement: “We have the right be horny.” The fact that the club shuns members who sleep with the same guy twice is an explicit acknowledgement of the bonding emotional power of sex, something the girls all want to avoid.

Volume I ends on a wrenching note, with Joe at a painful crossroads in her own sexual philosophy, and scenes from Volume II unfurl alongside the roll of credits. All of the talk in Volume I about lust and sensation and “cocks” (we get a gallery of different penises flashing across the screen) translates into some extremely dreary sex in “Nymphomaniac”, boring, bored, silly, embarrassing. You look at some of it and think, “What on earth is the point?” None of it is erotic. All that pounding and thrusting and grinding adds up to a keening unspoken awareness of the emptiness at the center of humanity, the looming presence of death, the doomed possibilities of not only connection, but feeling itself.

Sex can be many things, it can express love, hate, power, revenge. It can relieve boredom. It can be overlaid with intellectual considerations, or concerned with concepts such as consent, objectification, misogyny, the entire history of cultural baggage people bring into bed with them. “Nymphomaniac: Vol. I” addresses these heavy topics, but in a way that doesn’t feel heavy at all. The film is an intellectual high-wire act, death-defying, dangerous, entertaining, and delighting in its own inventiveness and daring.