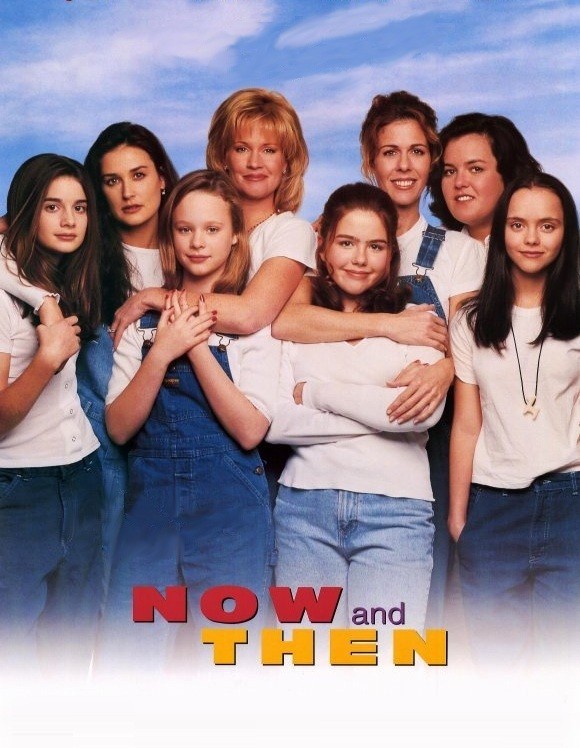

I would have liked to be a fly on the wall during the production meetings for “Now and Then.” The movie tells the story of four 12-year-old girls who do a lot of growing up during the eventful summer of 1970. But it begins with a reunion 25 years later, and the screen is filled with adult stars – Demi Moore, Melanie Griffith, Rosie O'Donnell and Rita Wilson – who we will scarcely see again until the end.

What was the purpose of the wraparound bookends with the big names? Why was it necessary for us to see who the girls grew up to be? As 12-year-olds, they made a solemn pledge to “always be there” if one of them was in need. Now there is a need: Christina, the Rita Wilson character, is pregnant, and although she has a husband and a gynecologist (played by O’Donnell), she needs the others, too. So the famous actress (Griffith) and the famous writer (Moore) return to the small town of Shelby, Ind., so they can participate in the tired cliche of still another of those natural childbirth scenes (“push! push!”).

The adult actresses are completely superfluous to the movie, which is a contrived “Stand by Me” kind of story. Although the screenplay isn’t much help, the four young actresses (Christina Ricci, Thora Birch, Gaby Hoffmann and Ashleigh Aston Moore) are wonderfully talented and would have been completely capable of filling the screen time without the guest appearances. In theory we might be interested in seeing what kind of women the girls grew up to be – but the movie gives the adults so little screen time that it has to resort to shorthand, like using smoking as a character trait.

The story takes place in an idealized subdivision where the girls have pooled their money to buy a treehouse from Sears (the price, $129 in 1970 dollars, buys them a cottage that is still standing 25 years later). Their imaginary lives are hyperactive; led by Samantha (Hoffmann), they venture into the cemetery one night for a candlelight seance, and develop a fascination for “Dear Johnny,” a boy who died young in the 1940s.

It is the summer they first begin to wear bras. Roberta, the tomboy, tries taping down her budding breasts, but Tina, the future actress, uses baggies of vanilla pudding to stuff her bra (later she will brag about her boob job). The girls communicate by walkie talkie, share secrets and ride to the county seat on their bicycles to look through back issues of the paper for clues about Dear Johnny.

They find them, along with tragic information about the death of one of their mothers.

Needless to say they also deal with boys in the movie, especially the hated Wormers, a gang of brothers who make their lives miserable. It is more or less obligatory, I suppose, that they steal the Wormers’ clothes down at the ol’ swimmin’ hole and get a glimpse of at least one Wormer penis.

Meanwhile, a recluse named Crazy Pete stalks the streets at night, and it takes the girls longer than anyone in the audience to discover his identity. For that scene, the film supplies one of those helpful storms that blow up whenever necessary, and a hokey scene in which a girl loses her bracelet and climbs down a flooding storm sewer after it. Watching this scene, I wondered what depths of desperation the filmmakers had arrived at in their need to create artificial tension.

What distinguished “Stand by Me” was the psychological soundness of the story: We could believe it and care about it. “Now and Then” is made of artificial bits and pieces. The director, Lesli Linka Glatter, says in the press notes that she started crying when she first read the script “because it captured that delicate evolution from girlhood to womanhood, and you so rarely find that.” I guess she didn’t see “Man in the Moon,” which has so much more truth and tenderness that it exposes “Now and Then” for what it is, a gimmicky sitcom.