In addition to a being packaged with a virtual reality experience at selected theaters, “Notes on Blindness” is being released in formats for blind and sighted audiences. I wish I’d been sent the former version. I just wanted to close my eyes and listen to the film’s realistic sounds and the narration by its subject, theologian John Hull. Hull made an acclaimed series of audio journal entries detailing how he coped with losing his sight. His work received several commendations from organizations for the blind, and it makes for powerful, compelling listening.

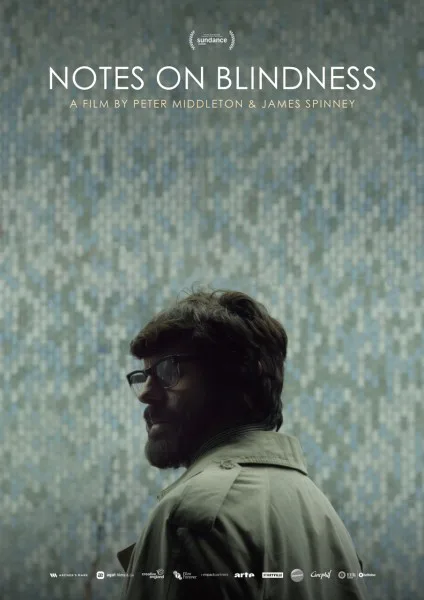

But the central conceit of “Notes on Blindness” is to emulate Hull’s descent into blindness using visuals. When directors Pete Middleton and James Spinney do clever things like keeping bits of information and action off-screen while we hear Hull’s frustration over having to ask for descriptions of what’s happening, the film achieves its goal. But quite often, the filmmakers go for blurry scenery, surreal events and odd camera shots that feel more like gimmicks than an accurate representation of its subject’s affliction.

My problems with overcoming the Uncanny Valley effect of the film’s gimmickry may stem from the fact that I am half-blind. I lost the vision in my left eye due to a retinal detachment when I was 14. So Hull’s discussions about ripped retinas and botched eye surgeries resonated greatly with me. And though I have a decent amount of sight in my good eye, I fully understood Hull’s initial unwillingness to accept his new condition. I felt the same way, and my similar fears were supported by the knowledge that my family is genetically predisposed to losing our vision. It’s more a destination than an option for us.

So Hull’s story was indeed inspiring to me. He continued to teach at the university he worked at pre-blindness, and he was devoted to bridging the gap of understanding between the sighted and the unsighted world until his death in 2015. But I couldn’t fully abide by the rules “Notes on Blindness” played by, though I suspect I may be in the minority here.

One thing that does work very well is the onscreen re-enactments of several journal entries by actors Dan Skinner and Simone Kirby, who lip-sync to Hull’s and his wife, Marilyn’s voices. This could have very easily been a distraction, but Skinner is excellent and Kirby practically vibrates with love for her onscreen husband. When Hull says on the soundtrack that, for the first time, he felt completely useless, Skinner nails the moment onscreen. There are also a few effective scenes with the child actors playing the Hull children; their inquiries about their father’s blindness are answered in a loving, supportive manner.

Hull’s journal entries contain enough memorable moments to warrant seeking them out. A meeting with a faith healer takes an unexpected turn. And Hull’s visit to his parents back in Australia begets the most haunting passages used in the film. He acknowledges that losing his sight has caused him to forget what many once-familiar things looked like, and this is especially distressing once he returns to his childhood home. The powerful nostalgia of his youth has slipped away, disappearing along with his vision.

“Notes on Blindness” has won several awards since its Sundance Film Festival premiere. If the subject interests you, don’t let my mildly negative review dissuade you from going to see it. I would like to see it again myself, but this time in the version I can share with several of my relatives whose vision is no longer present. I really think I’d like that version more, and I’d love to hear what my family thinks of It too. But you can keep the VR element. It can’t compete with the real thing for me.