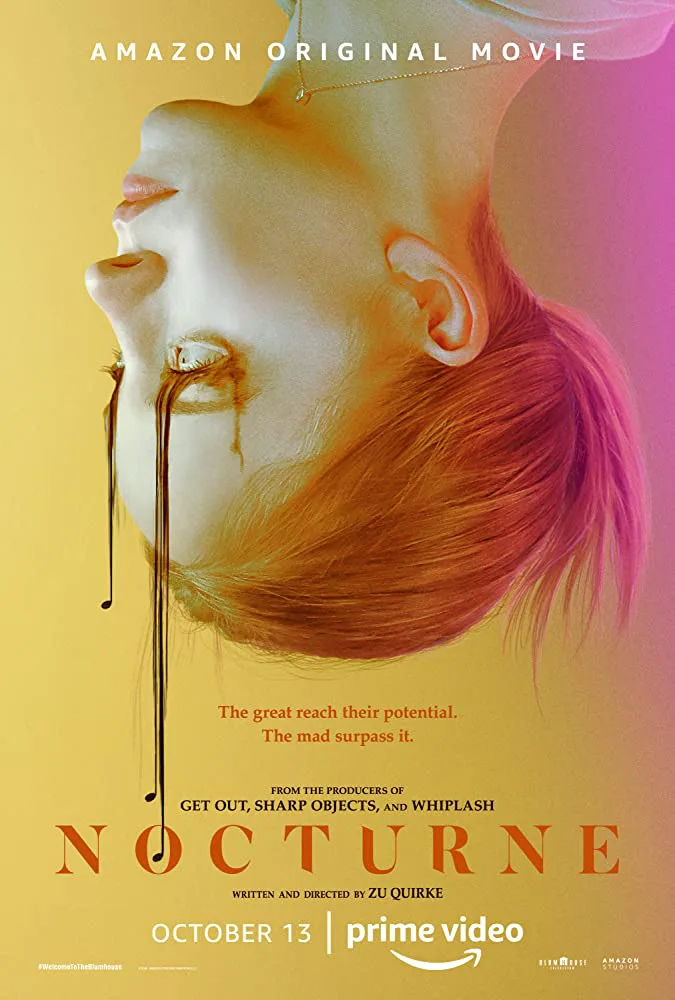

Zu Quirke’s “Nocturne,” released today in the “Welcome to the Blumhouse” anthology, echoes one of producer Jason Blum’s scariest but more unconventional projects—Damien Chazelle’s jazz thriller “Whiplash,” the movie that first put Blumhouse on the awards circuit. This story, about a classical pianist’s feverish pursuit for greatness, stands on its own with its more direct approach to horror, but it recalls the excitement of getting sucked into “Whiplash” and its musical approach to psychological terror. “Nocturne” isn’t just the best entry in the “Welcome to the Blumhouse” series, it’s one of the best Blumhouse movies in years.

Like that last great movie about musicianship as a bloodsport, “Nocturne” is filled with the horror of failure and mediocrity, as experienced by someone who has invested their self-esteem in hitting the right notes. Whereas Miles Teller’s jazz drummer in “Whiplash” goes through an emotional marathon practice by practice, Sydney Sweeney’s classical pianist in “Nocturne” is presented with a Faustian way around hard work, a shortcut to her hopes of becoming legend. She remains in the shadow of her twin sister Violet (Madison Iseman), who is also at the same classical music boarding school, but has already been accepted to Juilliard.

The source of this evil is creepy sheet music, which I’m not sure I’ve ever seen before. The images inside it are startling, with detailed, medieval graphics that foreshadow the steps Juliet can take to her destiny (“Purification, “Sacrifice,” etc.), which are tactfully actualized by the script’s zig-zag plotting. While the sheet music can be the most common way for the story to build and foreshadow, it’s a brilliant piece of Quirke’s transfixing and unique horror: why wouldn’t a series of notes make for a cursed piece of mythology, and then be passed along by endless hopefuls? On top of that, the movie depicts its Faustian deal without any figure verbalizing it. The pain of “Nocturne,” of Juliet being told that it’s too late for her to be like her sister or eventually like pianists like Pollini or Gould, is motivation enough for her to accept the dream that the notes show her.

Long before the cursed sheet music appears, Sweeney illustrates Juliet with a disturbing uncertainty of just how far this antisocial pianist would go to actualize that dream. From the beginning, she starts off relatively muted, especially as Juliet isolates herself from the world with a stern lock of her bedroom door, or pair of headphones. Throughout, her eyes beget desperation and intensity, and this builds on that sense of being so desperate for the end result that she loses focus on the music itself (she blacks out when she does play, as if it wasn’t even her playing). It’s an incredible performance from Sweeney, who shows many different shades of melancholia and mania with such acute work, all while picking away at the fortitude that Juliet had originally built around herself for the sake of her single goal.

Making her incredibly promising directorial debut, Quirke proves that storytelling about a classical style does not mean the filmmaking has to be recognizable. You feel the movie’s spiky creativity in even small choices, like interstitial music that’s far from classical, or jarring cuts to a new scene that’s suddenly in slow motion, or the way in which it suddenly throws you into a stylized dream sequence. Quirke’s commitment to the left-field helps the more commonplace horror stand out too—“Nocturne” can be legitimately scary, and its editing is particularly abrasive. Even the yellow sunlight that Juliet chases throughout the movie is freaky.

Quirke ramps up the film’s intensity scene by scene, showing a psychological implosion as Juliet starts to get what she wants. Juliet has a particularly intense rivalry with her “wombmate” Vivian, as Sweeney and Iseman battle in acerbic scenes that show sisters who have tragically grown apart due to a competition they’re addicted to, without any hope of reconciling. Their relationship viscerally shows the harrowing void that can come from extreme passion, especially for an art form that demands precision from such a young age, with only a select few people in the world ever having “it.”

“Nocturne” is a terrifying movie that cuts deep, and wields its brutal side tactfully. And it’s thrilling—thrilling to see a movie compound classical music geek-speak with an enveloping sense of dreaminess and dread, and to behold such an excellent lead performance that proves Sweeney absolutely has something special within her. She might just have “it.”

Now available on Amazon