Before he was killed in prison by another inmate in 1994, Jeffrey Dahmer’s crimes captured America’s attention through the seemingly boundless nature of his depravity. The Milwaukee-born serial killer claimed 17 victims before he was apprehended by police in his hometown. It’s perhaps unsurprising that Dahmer put up next to no fight when the arresting officers knocked on his door, accompanied by a would-be victim he’d let escape. He seemed ready for them, had made no attempt to conceal the evidence of his previous murders, nor the body parts in the fridge. He shuffled around the apartment, unaware of the personal space of the officers whom he breezed past handing out bits of evidence they asked for in the room. He didn’t struggle until it was clear that there was no getting out of the situation. Anyone who knew Dahmer as a kid would have recognized the despondent body language. Dahmer never grew past his miserable, depressed teenage self. He’d simply channeled his alienation into unspeakable mutilation and sexually charged murder.

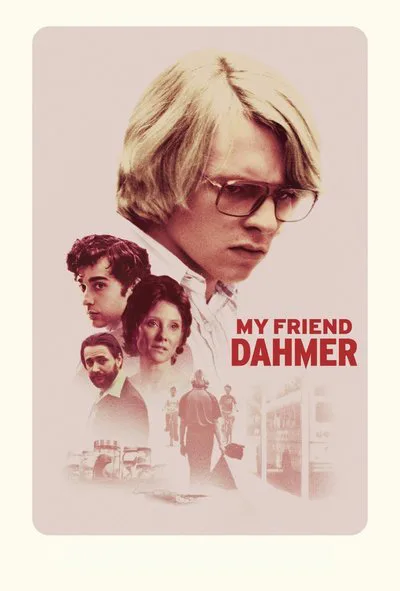

It’s that teenage self that occupies Marc Meyers’ excellent and disturbing “My Friend Dahmer,” based on the graphic novel by cartoonist/artist John Beckderf, who knew Dahmer as a kid. There have been many different films (not to mention books and articles) about Dahmer such as “The Dahmer Files,” an intriguing, laconic documentary about his arrest, and David Jacobsen’s “Dahmer,” which goes back through his history, eventually arriving at his first murder, the strangulation of Steven Hicks in 1978. “My Friend Dahmer” ends just before Hicks’ murder, trying to get a fix on the 18-year-old who decided to take a stranger to his parents’ abandoned house. The movie shies away from easy psychoanalysis of the murderer, choosing instead to let the audience draw their own conclusions. The movie thankfully doesn’t try to make it seem as though bullying, alcoholism, his parents’ divorce, his burgeoning homosexuality, or even a cocktail of the above, were responsible for his actions. He may have been mentally ill but he rejected help and chose violence and anti-social behavior at every turn.

When we meet Jeffrey Dahmer (Ross Lynch), he’s just north of being a complete outcast at school. He quietly hates his only friend Oliver (Jack DeVillers) and won’t stand up for him when bullies attack, because if they’re picking on someone else, that means they’ll leave the quiet, roadkill-collecting Dahmer alone. His parents (Anne Heche & Dallas Roberts) fight so often that their eventual separation feels like a blessing. A chance encounter during class with the young John Beckderf (Alex Wolff) sets the tone for his last year of high school. ‘Derf’ and his close circle of friends admire Dahmer’s fearless disruptions of social norms. He pretends to have fits of mentally disturbed behavior in class and in public places, a performance the kids dub “doing a Dahmer,” and so they make him their ‘mascot’ and base at least a semester of practical jokes around his willingness to degrade himself for laughs. As Dahmer strains harder and harder for laughs and approval that don’t manifest, he starts drinking heavily, while Derf and his crew grow a conscience about their treatment of their friend, whom they slowly realize is more disturbed than they imagined. Of course, they didn’t get a first-hand look at his mother’s degrading mental state, his habit of killing and chemically skinning animals, or his fixation on a hunky neighbor (Vincent Kartheiser). It turns out the last thing Dahmer wants from them is an apology or pity. What he wants is to hurt someone, and it grows increasingly clear it doesn’t matter who that turns out to be.

Beyond every odd gesture is the knowledge that this unhinged hulking teen will start killing when the curtain falls on this chapter of his life. The film doesn’t forecast his crimes, refusing to turn chance into clues. There’s a bit of knowing queasiness when his father buys him the weights he’ll later use to kill Steven Hicks, but the film doesn’t show the crime, so it doesn’t register as anything other than tragic coincidence for those in the know. Meyers is more interested in rendering the environment and deteriorating stability of a lost kid. The saturated colors (which are beautiful even when just a plethora of ‘70s browns and beiges) fill every room with portent and a beauty that seems purposely incongruous. There’s a composition near the beginning of the film when Dahmer tries and fails to impress two classmates in his shed full of jarred animal remains that’s both haunting and grammatically impressive. The approaching moonlight has turned the forest deep, almost neon green while the orange light (complete with Tobe Hooper lens flare) of the exposed halogen bulb hanging from the roof of the shack bisects the frame, showing clearly the natural darkness Dahmer refuses to acknowledge, as well as shrouding him in silhouette in a dark wooden cabin like a malevolent boogie man figure. For a few seconds the movie looks like it’s about to turn into “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” but naturally life is never that easy to determine and the film never makes it that easy to situate yourself in Dahmer’s story. He could have chosen to talk about his problems at any point and this would have been a very different story.

That kind of quiet intelligence animates the film at every turn. Ross Lynch is eerie and impressive as Dahmer, even if his constantly hunched posture and Frankenstein-gait seem a little too big. Look at his eyes during the scene where Derf suggests he become their mascot, darting back and forth, as if joy is so foreign to him that he’s searching his brain for some other emotion to replace it. His looks of longing at Kartheiser’s Dr. Matthews are also varied and rich, never communicating anything as simple as lust. He sees something more in this man than just the answer to the puzzle that is his sexuality. When he manages to trick Matthews into giving him a physical under false pretenses the scene ricochets from glee to disgust as he discovers his young patient’s motives. It’s an unnerving but oddly moving scene and shows the minor problems that become monolithic trials when you’re young. Heche and Roberts do similarly impressive work as Dahmer’s squabbling, uninvolved parents. Roberts’ perpetually downtrodden Lionel Dahmer’s hangdog approach to family is so easy to understand and sympathize with, and Heche finds a sort of dignity for the clearly unwell Joyce that keeps their white noise arguments consistently engaging and understandable.

In short, Meyers recreates Dahmer’s world so wholly that you don’t leave with questions even if the big one remains purposely unanswered. There is nothing in this expertly-drawn character study that attempts to solve the mystery of Jeffrey Dahmer, because life rarely hands us those answers. The Dahmer who let the police into his apartment at age 30, unable to predict his impending arrest until it’s too late, was plainly still the kid who made a scene at school whenever possible. It was never about how he was treated by other people, it was always about him.