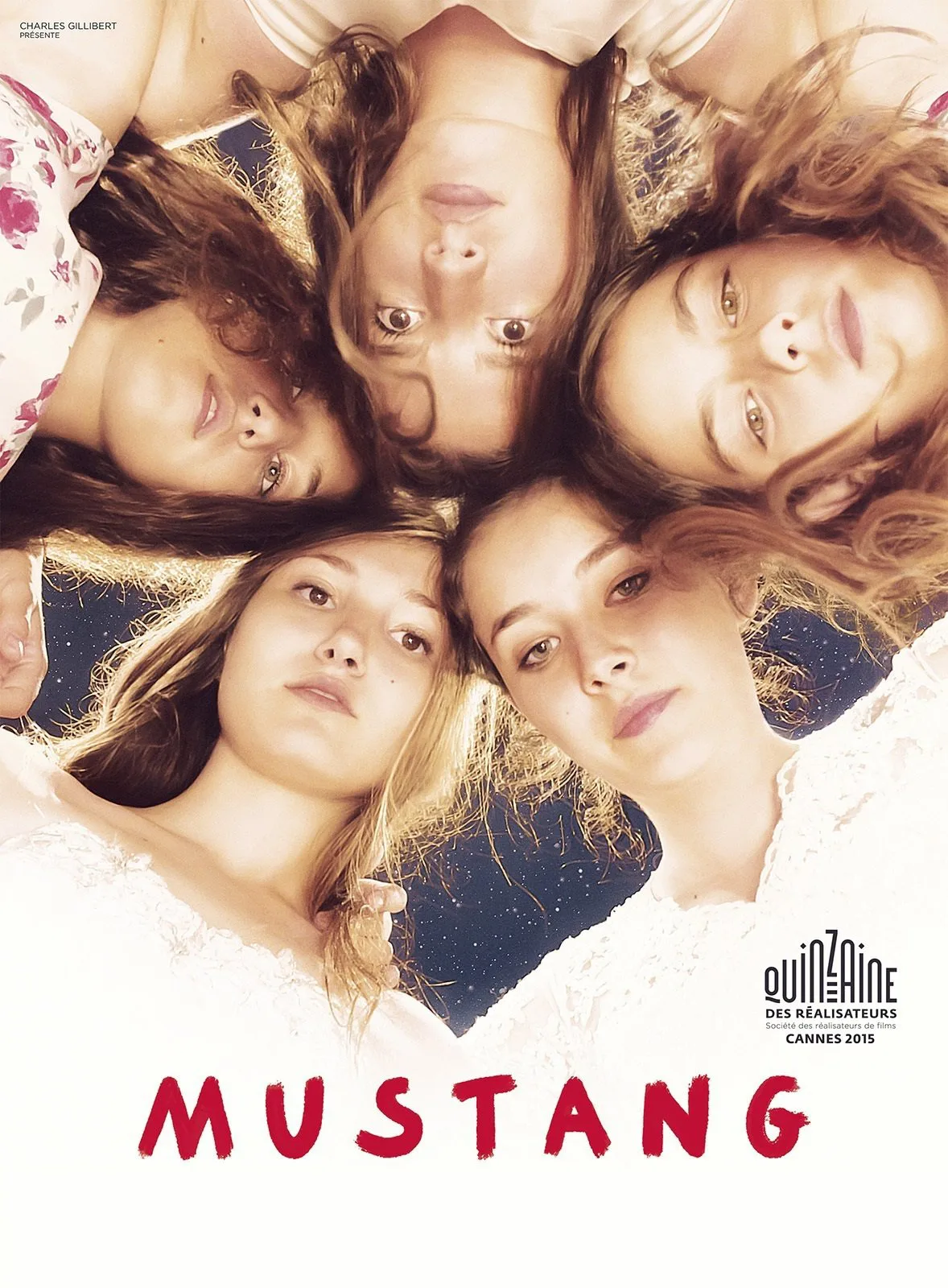

Five beautiful and beguiling young sisters become imprisoned in their own home, forbidden by their controlling, conservative elders from having any contact with the outside world—especially boys.

The premise of “Mustang” may sound familiar—and visually, director and co-writer Deniz Gamze Ergüven does seem to have borrowed a few cues from Sofia Coppola’s stirring 1999 debut, “The Virgin Suicides,” in making her own feature film debut. But “Mustang” grabs you with its own sense of haunting melancholy, as well as an increasing feeling of urgency and outrage.

Set in a coastal town in northern Turkey, “Mustang” puts a cultural spin on stories of teen-girl angst and sexual blossoming that probably will seem infuriating to many viewers in its closed-mindedness, its archaic inflexibility. But while it takes place in a very specific part of the world, its emotions are universally recognizable, as is the powerful yearning of its young, female characters to establish their own identities and assert their own desires.

Ergüven very quickly and efficiently establishes who these girls are and what their dynamic is in the script she co-wrote with Alice Winocour, both with each other and with the outside world. They are a tribe unto themselves with their long, brunette tresses, plaid schoolgirl uniforms and a shared conspiratorial vibe. And so when “everything turns to shit,” as free-spirited, youngest sister Lale (Günes Sensoy) so aptly puts it in the film’s opening voiceover, we have a sense of why this matters. There’s a tangible weight to the shift that occurs.

And yet, Ergüven maintains a light, gauzy intimacy as she chronicles the girls’ increasing imprisonment in their house—and includes enough bursts of energy to suggest that their collective rebel spirit could blow the doors off at any moment.

It all begins innocently enough on the last day of school with an expression of adolescent jubilation that will resonate with viewers regardless of ethnicity or age. Lale and her older sisters—Sonay (Ilayda Akdogan), Selma (Tugba Sunguroglu), Ece (Elit Iscan) and Nur (Doga Zeynep Doguslu)—dash down to the beach to frolic in the Black Sea with a few of their male classmates. As they splash, swim and engage in chicken fights, the mood is playful but infused with an underlying tension, thanks in part to the hum of a low-key, synth score.

After a walk through what turns out to be a symbolic apple orchard, the girls return home to a tirade and individual beatings behind closed doors from their grandmother (Nihal G. Koldas), who’s raised them since their parents died a decade earlier. Turns out an elderly neighbor saw the sisters playing on the beach and misinterpreted their innocuous romping as something far more depraved. “Everyone is talking about your obscene behavior,” she shouts. And so she and the girls’ old-fashioned, judgmental uncle, Erol (Ayberk Pekcan), quickly lock up the grounds and round up anything in the house that could possibly corrupt them further, including phones, the computer, photos and magazines. (Although, to Ergüven’s credit, she gives “Mustang” a timeless feel by not making it clear exactly when the story takes place. It could be 20 years ago. It could be this week.)

Grandma sews them frumpy, shapeless frocks to wear and invites the village’s elder women over to teach them how to serve tea, stuff comforters and make dolmas. “The house became a wife factory that we never came out of,” Lale laments as our clear-eyed narrator and guide. And sure enough, neighboring families start arriving to offer their sons as the girls’ husbands, one by one.

As depressing as all this sounds—and as quietly damning as “Mustang” is in its depiction of patriarchal oppression—the way the girls react to the tightening of the vice around them provides a consistent source of surprise and even hope. Each responds differently, from acquiescence to defiance, but their loyalty to each other and the strength of their sisterly bond remains true. They’re such a cohesive unit that it’s sometimes hard to tell them apart, such as when they’re goofing off on the bedroom floor in a tangle of wavy hair, long limbs and giggles. And the fact that Ergüven chose non-professional actors to play these five vibrant young women gives the film an added layer of authenticity.

She leaves some questions unanswered, though: how do the sisters feel about their parents’ absence, especially as their current living situation grows increasingly grim? And a couple of the middle sisters get lost in the shuffle, personality-wise. But their collective story adds up to a deeply moving whole, and its conclusion brings the narrative full-circle with an image that’s simple but powerful in its sense of possibility.