“Hey girlfriend

I got a proposition goes something like this:

Dare ya to do what you want

Dare ya to be who you will

Dare ya to cry right out loud.” — Bikini Kill, “Hey Girlfriend”

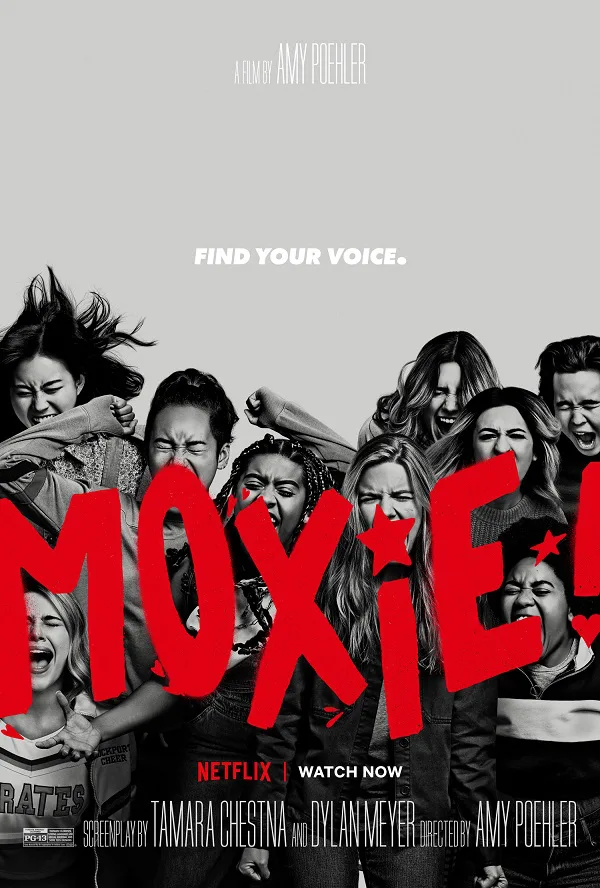

Those “dares” sound so simple, but they’re not, particularly in high school. High school is difficult for girls, but it’s difficult for boys, too (at least girls aren’t told “girls don’t cry” from the moment they’re born.) Girls, though, have their own specific challenges navigating a conformist world, and that’s the world portrayed in “Moxie,” based on a YA novel by Jennifer Mathieu. With a talented young cast, “Moxie” takes its inspiration from the riot grrrl era of the ’90s, from Bikini Kill (the punk rock feminist band most associated with riot grrrl), and, most of all, from the riot grrrl ‘zines: self-created, self-designed, photo-copied, these ‘zines spread across the country. In “Moxie,” a current-day teenage girl named Vivian (Hadley Robinson) ignites a raging feminist movement in her high school, after discovering a treasure trove of riot grrrl memorabilia in her mother’s trunk. Directed by Amy Poehler, “Moxie” is both an awkward act of nostalgia for ’90s activism and an attempt to push the riot grrrl legacy into the future.

High school is high school, no matter the era. There are popular kids. There are those who want to be popular. There are those who are left out. These dynamics are particularly toxic in the high school in “Moxie,” where “rankings” are published on social media every year, rankings like “Best Rack,” “Most Bangable,” etc. Vivian finds it annoying, but also doesn’t have any sense she could push back. Her cluelessness is challenged when a new girl named Lucy (Alycia Pascual-Peña) makes waves, first by challenging the summer reading list, and then by standing up to the menacing cocky football-player bully, Mitchell Wilson (Patrick Schwarzenegger). When Lucy reports Mitchell’s harassment to the principal (a soothing-voiced Marcia Gay Harden), the principal warns Lucy not to say the word “harassed” and to just suck it up and ignore him. Basically “boys will be boys.” Vivian and her best friend Claudia (Lauren Tsai) are not “trouble-makers” like this, but something about Lucy’s fearlessness inspires Vivian. Vivian’s mother (Amy Poehler) is a cool mom (although not like the grotesque “cool mom” Poehler played in “Mean Girls“), and one night Vivian discovers her mother’s punk-rock past. It’s the ‘zines that grab Vivian’s attention. She decides to put out her own and she calls it “Moxie.”

The zine, calling out the boorish behavior of boys and the sexist administration, immediately makes waves. Vivian doesn’t take ownership of Moxie. Anonymity is key. Girls gather together, almost by osmosis. There’s Lucy, fired up by the possibilities of expanding her protest. There’s Kiera (Sydney Park) and Amaya (Anjelika Washington), two talented athletes infuriated that their championship soccer team doesn’t get as much support as the lack-luster boys’ football team. There’s Kaitlynn (Sabrina Haskett), a girl sent home for wearing a tank top. There’s CJ (Josie Totah), a trans girl angry that she’s not allowed to audition for the role of Audrey in Little Shop of Horrors. The movement sweeps the school, and causes a rift between Vivian and her rule-following best friend Claudia.

Tamara Chestna and Dylan Meyer adapted Mathieu’s book for the screen, and the script tries to do too much on occasion, as evidenced by the film’s slightly bloated run-time. The attempt to make the feminism of “Moxie” intersectional is well-meaning (and necessary), but leads to some inadvertent tokenism in the execution. Nineties riot grrrl was criticized for not being inclusive enough, something Poehler’s character admits, and so “Moxie” is a sometimes-awkward attempt to course-correct. There are missteps though. Lucy, so central to the film’s early sequences, takes a backseat, at least in terms of screen time, once the movement is up and running. “Moxie” doesn’t have the satirical bite of, say, “Mean Girls,” nor does it have a particularly punk rock energy, but Poehler does an admirable job keeping things moving. Boys aren’t left out, either. A kid named Seth (Nico Hiraga: you probably remember him from “Booksmart“) is a shy ally of the Moxie movement. The romance that blossoms between Seth and Vivian is very sweet, but it has its nuances, too. At one point, Vivian, hyped-up on feminist outrage, includes him in her generalized critique, even though he hasn’t done anything wrong. This is very insightful! Hiraga is a natural as a young romantic lead.

The soundtrack is dominated by Bikini Kill, particularly “Rebel Girl,” also covered in the film by the teenage band The Linda Lindas. Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of Bikini Kill, is seen by many as the avatar of riot grrrl, although Hanna would be the first to say she was no leader. Mainstream media shied away from the radical feminist lyrics of bands like Bikini Kill, and mostly portrayed “riot grrrl” as a fashion choice, all those plastic barrettes and baby-doll nighties, etc. Not everyone was on board. Courtney Love, for example, lead singer of Hole, was often looped into riot grrrl by the media, who only saw her wardrobe. Love balked against this, making public statements about her disagreements with the movement’s middle-class concerns: “Who told them it was their undeniable American right not to be offended?” Today, one needs only look to Russia, to the persecuted protest collective Pussy Riot, to see that the riot grill energy is alive and well. There have been a couple of books and documentaries about the riot grrrl scene, but so far it hasn’t made many meaningful inroads into feature film narratives. There are a few exceptions. 2014’s “Kelly & Cal” stars Juliette Lewis as an ex-punk-rocker, now married and pregnant, looking back yearningly on her wild feminist past. Elisabeth Moss in “Her Smell” played a rock star who rose to prominence in the riot grrrl era, until self-destructing in spectacular fashion. “Moxie,” geared towards a younger audience, is an attempt to pass on the torch.

One of the most important lines in “Moxie” comes from uptight Claudia. Vivian is frustrated by Claudia’s lack of involvement in the protests, and abandons her to hang out with her new group of like-minded friends. Eventually, Claudia says to Vivian, “I do care. You just need to let me do it my way, okay?” “Moxie” allows for this point to be made, and strongly, across a diverse group of participants. Any group that demands monolithic conformity—or only includes a certain kind of person with a certain kind of outlook/background/attitude—does not deserve to call itself liberating. “Moxie” gets that.

Now available on Netflix.