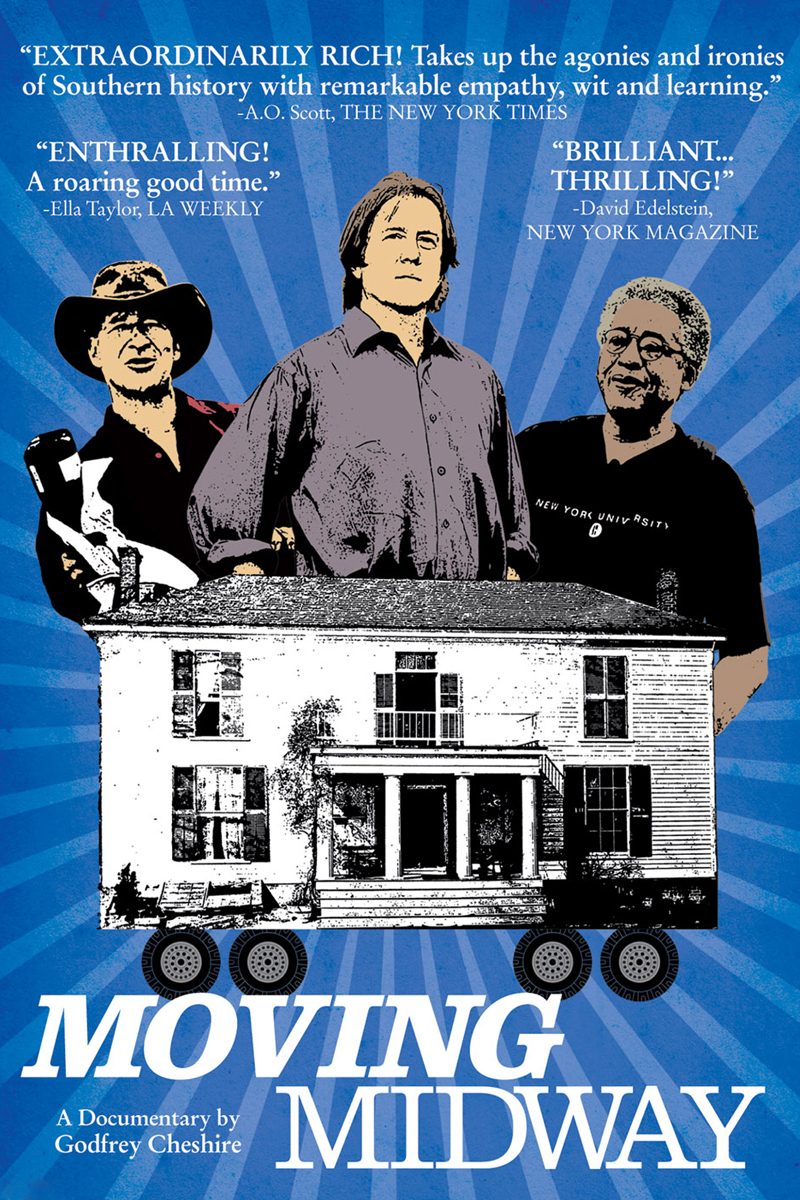

“Moving Midway” tells three stories, each one worthy of a film of its own. (1) It records the journey home to North Carolina of the film critic Godfrey Cheshire, and his discovery of his family’s secret history. (2) It documents the ordeal of moving a 160-year-old Southern plantation house to a new location miles away, not by road but overland. (3) It demolishes the myth of the Southern plantation.

Movie critics are always asked if they’ve ever wanted to make a movie of their own. A handful, like Peter Bogdanovich and Rod Lurie, have had success with features. Others, like Todd McCarthy, have made good documentaries. Godfrey Cheshire’s first film follows the first rule of both kinds of films: Start with a strong story that you feel a personal connection with. His story grows stronger, and the connections deeper.

Like many critics (the Alabama-born Jonathan Rosenbaum comes to mind), Cheshire was a small-town boy who moved to the big city. First it was Raleigh, and now New York. In North Carolina, his youth revolved around Midway Plantation, outside Raleigh, the family seat since 1848. In 2006, the ravages of progress overran Midway. It was boxed in by two expressways. Best Buy was across the street. Target and Home Depot were moving in. Godfrey’s brother Charlie hired experts to jack up the house, put it on wheels and move it to 60 or 70 acres deep into the country.

Godfrey went south to film this undertaking. It stirred family memories, and stories about the ghosts many people thought they had seen in Midway. Then he heard from an NYU professor of African-American studies named Robert Hinton, who said he was related to the family; Hinton is the ancestral name. Robert is African American. Godfrey invited him to come to North Carolina, visit the house and watch the move.

Hinton had written about a much-publicized North Carolina family reunion that reunited the black and white members of the same plantation family. Now he received an e-mail from a Brooklyn teacher named Al Hinton, who said his 96-year-old grandfather, Abraham Lincoln Hinton, had some memories to share.

His mind clear as a bell, Abraham recalled, during a visit by Godfrey and Robert, that his father, born in 1848, took him past a big white two-story house and told him it was his birthplace. That was Midway. According to oral tradition in the African-American branch of the family, they were descended from a Hinton patriarch and a cook who was a black slave. There seems no doubt, both in genealogy and physical evidence: Every Hinton, white and black, has the same distinctive nose, which can clearly be seen in the portrait of their common ancestor.

Cheshire made these discoveries while filming, and Robert Hinton became co-producer. He considers the myth of the idyllic plantation as formed in works like “Birth of a Nation” and “Gone With the Wind,” and demolished by “Roots.” Hinton, whose slave ancestors constructed Midway and picked cotton there, is a succinct and sometimes droll observer. He surprises Cheshire by telling him he considers Midway part of his own heritage, and again when he says it doesn’t bother him at all that the original land will be buried beneath a parking lot. Robert on Civil War reenactments:

“I’m comfortable with the idea that they keep refighting it, as long as they keep losing it.”

Invited by Al and Abraham to a Hinton family reunion, Cheshire finds he has more than 100 African-American cousins, all of whom know exactly who they are descended from. “It is becoming clearer,” he says, “that the South is a mixed-race society.” Robert Hinton reveals to him: “I found after I came North that I was more comfortable with Southern whites than with young blacks up here.” When Cheshire’s lively mother, Sis, and the stately Abraham meet, they are instantly at ease, even kidding with each other. Not that Sis doesn’t believe the slaves, by and large, were taken good care of.

This is a deceptive film. It starts in one direction and discovers a better one. Cheshire is a dry, almost dispassionate narrator, and that is good; preaching about his discoveries would sound wrong. Robert Hinton, whose feelings run deep, brings the story into focus: “I always wanted to meet a white Hinton. I was hoping I would hate him. The problem is, I like you, so I can’t lay a lot of stuff on you.” He is philosophical, but not resigned. There is a difference.

Meanwhile, at the new Shoppes of the Midway Plantation mall, there is a restaurant named Mingo’s. That was the name of Midway’s first slave. The mayor, bursting with civic pride about the new development, explains how we have all moved on and outgrown the troubles of the past. The mayor is black. We are now in the 21st century.