You are away from home for two or three years at a stretch. You belong to a band of armed men, who patrol the desolate Kekexili region of Tibet in mud-covered Jeeps and military vehicles. Your existence is sanctioned by the government, but you are not “officially employed.” You have not been paid in a year. Your leader observes, “We are short of men, short of money, short of guns.” You are four miles above sea level, the air is thin, the sun pitiless, you cannot see a living thing on the horizon, and there are others out there, better equipped, ready to kill you.

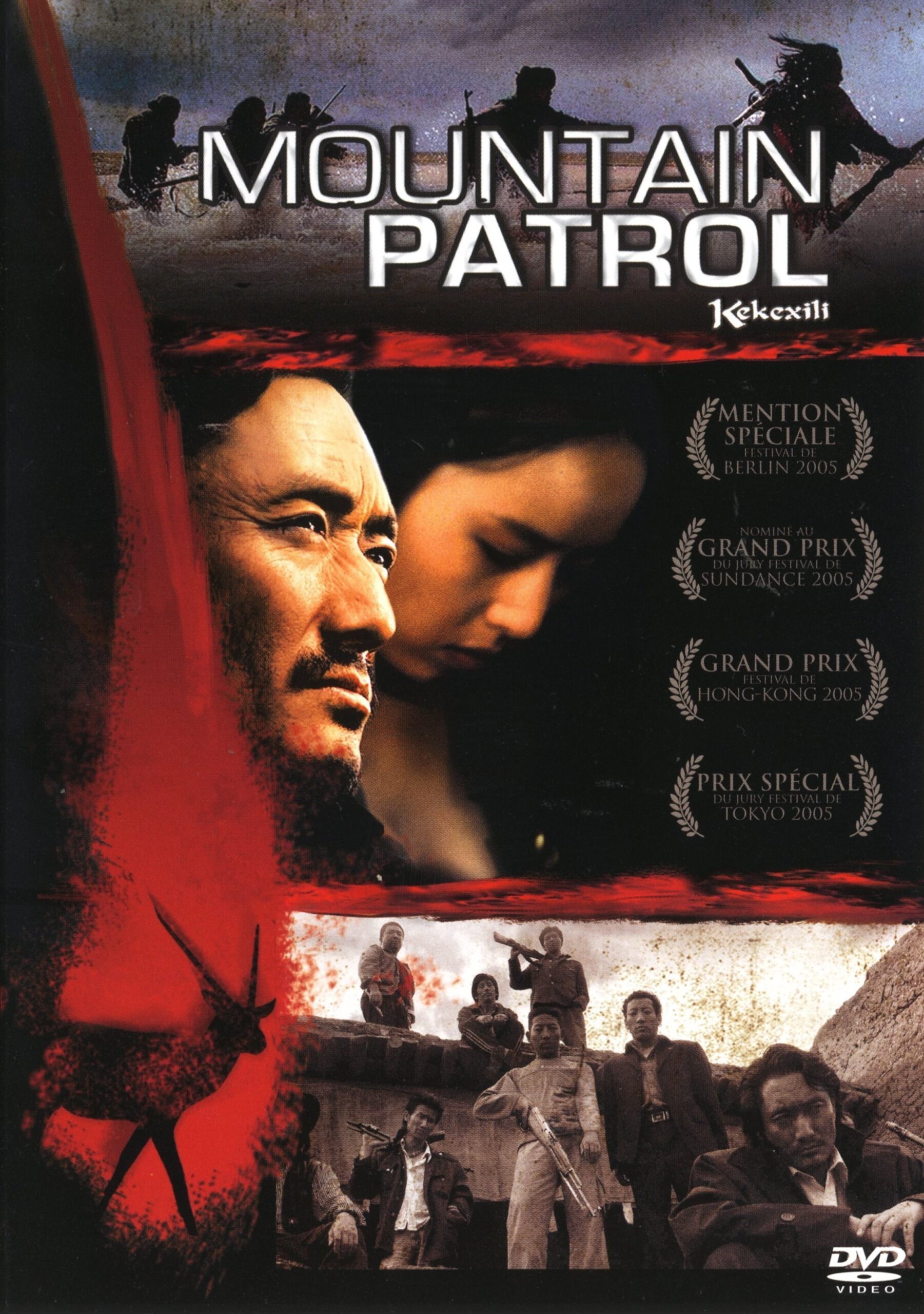

This is the life of the characters in “Mountain Patrol: Kekexili,” and what is their mission? To save the endangered Tibetan antelope, whose pelts were so prized by silly women that their population was reduced in the 1990s from millions to thousands. Why do you dedicate your life and endure this misery for such a cause? The movie contains no idealistic speeches, and the patrol members are not tree-huggers.

A journalist from Beijing (Lei Zhang) ventures to this far country to spend some time living with the mountain patrol. He meets their legendary leader, Ri Tai (Duo Bujie). They roar off into the desolation, a band of hardened men, hunting their dinner, roasting it over fires, cutting it with knives that are also weapons. Ri Tai is a man of few words, a man consumed by his mission, and he and his men remind me of the desperados in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. They are hunting poachers instead of Native Americans, but their focus is as intense. They consider themselves the hand of justice.

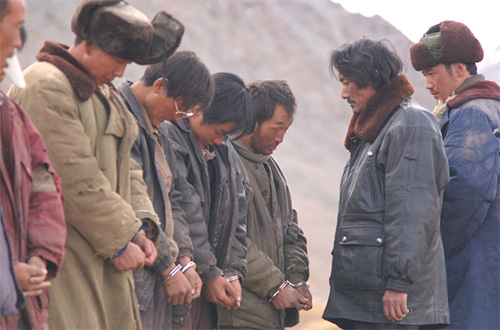

What is remarkable is that this film is based on a true story, and filmed on the actual locations. These are hard, violent men, risking their lives to save an animal species. In appearance and behavior, they could be commandos, insurgents, terrorists. The poachers are no less desperate, and the film opens with the murder of a patrolman. In a strange way, the patrol and the poachers feel a bond; they are the only humans on this high plateau, both drawn there by a fascination for the antelope, and they share an existence no one else knows.

It is conventional to speak of the beauty of a vast unspoiled wilderness, but the Kekexili is not where you would choose to live for three years. It is very dry. Color has been bleached from the land, which is sand and ochre and stark shadows. The desert offers to relief, and the mountains offer ambush. There is a particularly horrifying scene where a man steps into dry quicksand. He struggles, and then he simply stops moving and becomes utterly passive as inch by inch he sinks to his death, and then there is nothing to show he was there.

The journalist makes some discoveries. Ri Tai, the patrol leader, tells him that when they capture antelope pelts from the poachers, they sometimes sell them, because it is the only way to finance their operation. He explains that technically they lack the power to arrest the poachers, although in this country where anyone can disappear without a question, the measures they take are not closely scrutinized. When after long intervals they return to their wives and families, the women seem to accept their mission, although some wives, even in Tibet, might reasonably ask why their husband must leave his family unprovided for while roaming around in search of poachers.

“Mountain Patrol” is a Chinese film, which raises questions that are hard to answer. Is it designed to paint a positive picture of China’s occupation of Tibet? Or can it be read as a parable: Protecting the antelope from poachers is the same as protecting Tibet from Chinese poaching? Because there are no ideological speeches, because the movies of the patrolmen are expressed in actions instead of words, we cannot be sure.

One of the American distributors of the film is the National Geographic, and in its landscapes and ethnographic insights, this looks at times like a documentary. But it plays like a Western involving foes who are equally hard and unsparing. The movie leaves us with the encouraging news that the Chinese government has taken over patrol duties, that the poaching has been reduced, and that the antelope herds are starting to grow again, that rich women no longer have the nerve or the heart to wear shawls made of shahtoosh, the wonderful fabric made from the pelts of the murdered Tibetan antelope. We are also left with wonder about what drew these desperate men to this desolate place for their thankless struggle.