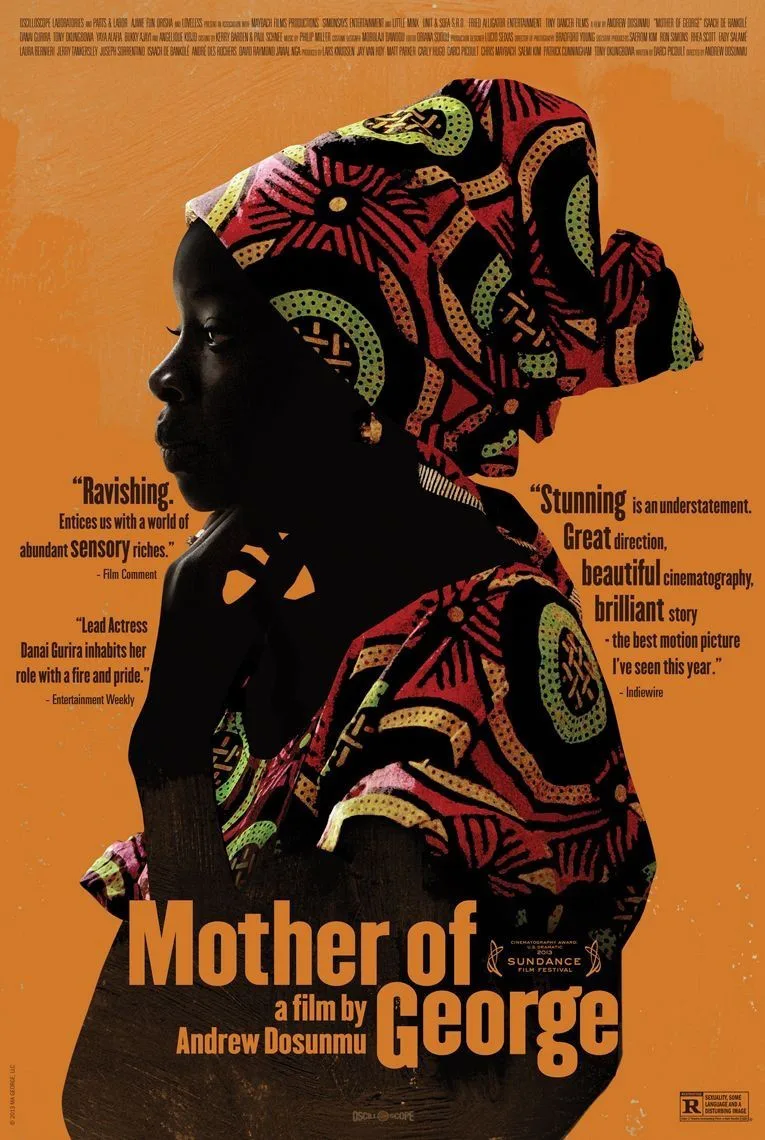

A stunningly imagined account of African immigrant life in present-day Brooklyn, the Sundance-prizewinning “Mother of George” is a film with a visual manner so unusual and forcefully elaborated that it could conceivably overwhelm any story it was used to tell. Thankfully, though, director Andrew Dosunmu evidences a sure sense of how all his cinematic elements fit together. The result is a work in which style and story unite to create a singularly mesmerizing look at a culture within a culture.

Shortly after the film begins, Dosunmu, working from a script by American playwright Darci Picoult, takes us into a wedding of two immigrants from Nigeria. In this long but entirely riveting scene, there are patches of dialogue and the important beginnings of a narrative, but what mainly holds the viewer’s attention is the film’s precise, absorbingly articulated look at the ritual and its rich physical and human textures, including the array of traditional costumes and strong African faces (provided by dozens of extras with Yoruba tribal backgrounds). If Gordon Willis’ imagery for the “Godfather” films set the standard for the use of a dark photographic palette, Dosunmu and cinematographer Bradford Young do something comparable here, and the outcome is just as enrapturing.

The wedding in this scene unites Ayodele (Isaach De Bankolé), the proprietor of a successful African restaurant in Brooklyn, and Adenike (Danai Gurira), a young woman who’s much closer to her African roots. At first glance they seem well-matched: he’s proud and confident, she’s self-possessed but also demure and eager to please. Surrounded by family and well-wishers, they appear to have the best of the old world and the new. While the advantages of New York are all around, the two enjoy the support of a strong traditional culture that has been successfully transplanted from Africa. This auspicious combination seems to be summed up by Ayodele’s strong-willed mother (Bukky Ajayi), who wishes the couple “prosperity and fertility.”

The first of those goals essentially has already been achieved, thanks to Ayodele’s hard work as a restaurateur. The second one is the rub, and the narrative’s engine. While the couple’s marriage is passionate, months pass and there’s no pregnancy to report. (They hope for a boy, who will be named George after a deceased relative.) Both husband and wife seem to assume that the problem must lie with her, but Ayodele staunchly refuses to take another woman to bear his child, as custom allows. More and more perplexed at her inability to conceive, Adenike consults a friend, who steers her to a fertility specialist.

The doctor, though, offers tests that would need to involve both husband and wife, and that are expensive. Ayodele scoffs at both the idea that he needs test and at spending money on such foolishness. Unhappy and desperate, Adenike increasingly comes to suspect that the problem may really lie with Ayodele. Her crusty mother-in-law apparently agrees, and offers a solution: Adenike should conceive a child with her husband’s younger brother, Biyi (Tony Okungbowa). “It’s the same blood,” the old woman shrugs. Adenike naturally is shocked at the idea. But what can she do? Is it better to accept her mother-in-law’s urging and insert a massive deception into her marriage, or to watch that marriage founder due to childlessness?

Though a rather simple melodramatic conceit at its core, Adenike’s dilemma is fascinating not only for the emotional torque it involves, but also for the interplay of larger cultural forces it implies. Although in many ways he has become a modern American entrepreneur, Ayodele’s assumptions about his wife’s fault in the matter of infertility, like his refusal to join her in trying to find a solution, reflects a kind of patriarchal thinking imported from the old world. Yet that itself is balanced by an equally traditional and forceful matriarchal impulse in the person of Ayodele’s mother, the real power-behind-the-throne in this off-kilter marriage, who asserts a very different “right to choose” that puts all control in the mother’s hands.

Bringing this resonant trans-cultural drama to life, Dosunmu elicits memorable performances from an exemplary cast. While the formidable De Bankolé skillfully makes Ayodele both warm and remote, a good man derailed by pride, the film’s revelation is the Adenike of Danai Gurrira, whose face registers the tumultuous changes caused by her body having become a de facto battlefield. Dosunmu seems to relish contemplating that face, which becomes a key element in his film’s extraordinary stylistic display.

Visually, “Mother of George” is one of those rare films—Bertolucci’s “The Conformist” is another—in which every shot seems to belong on a museum wall. Dosunmu uses a whole panoply of techniques, from strangely off-center compositions and shallow-focus emphases (he will sometimes show us just the top of a subject’s head, or part of a face) to insinuatingly slow camera movements, in addition to Young’s dark palette and naturalistic lighting. The director has a background that includes fashion photography and music videos, and the kinds of tools he borrows from those fields can sometimes bring to a movie nothing more than a hyper-aesthetic surface that suffocates everything beneath. In “Mother of George,” they contribute a look—call it dream-like hyperrealism—that is part of a remarkably cohesive whole, not just a stylistic tour de force but a comprehensive and persuasive vision of a vibrant culture still in the process of being born.