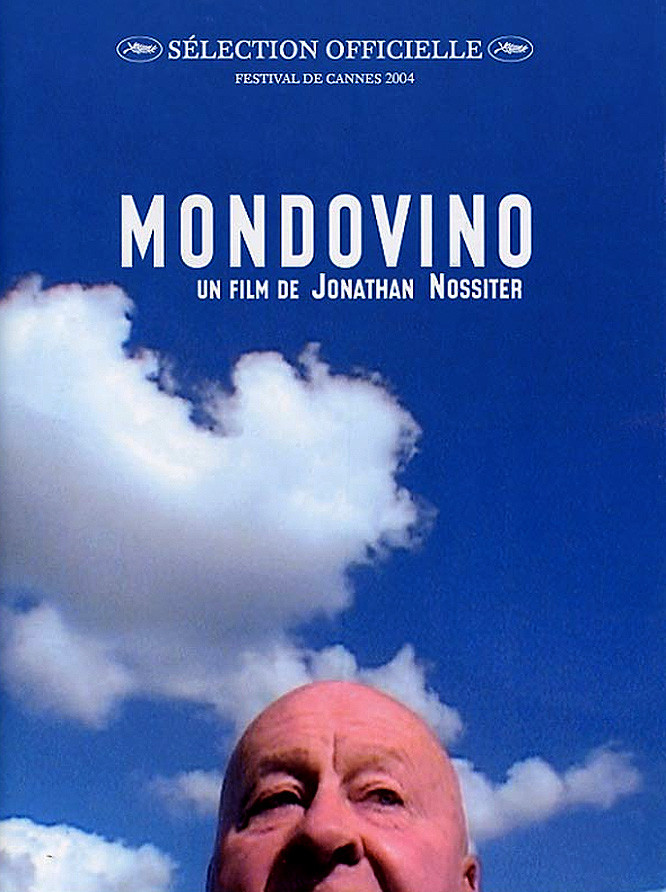

“Mondovino” applies to the world of wine the same dreary verdict that has already been returned about the worlds of movies, books, fashion, politics, and indeed modern life: Individuality is being crushed, marketing is the new imperialism, people will like what they are told to like, and sales are the only measurement of good. Briefly (although his movie is not brief), the wine lover Jonathan Nossiter argues that modern tastes in wine are being policed by an unholy alliance involving the most powerful wine producer, the most ubiquitous wine adviser, and the most influential wine critic. Together, they are enforcing a bland, mass-produced taste on a world of wine drinkers who fancy themselves connoisseurs but basically like what they are told to like.

This does not surprise me, since I have long suspected that oenophile is a polite word for a trainee alcoholic who has money and knows how to pronounce the names of several wines that have worked for him in the past. I thought “Sideways” was particularly observant as it watched Miles, the oenophile played by Paul Giamatti, advance during the course of a day from elaborate sniffing, chewing and tasting rituals to pouring the bucket of slops over his head. I treasure the Mike Royko column in which he advised the insecure on how to deal with a snotty sommelier: He will present you with the cork. Salt it lightly and eat it. This will clear your palate.

There are people who know good wine from bad, and some of them are in this movie, although you will have to take their word for it, all the time remembering that every wine drinker thinks he knows good wine from bad, even at the level where Paisano is judged superior to Mogen David, as indeed some believe. “Mondovino” says distinctive wines are being punished because they do not taste familiar; the unique local taste of great wines is being leveled by “micro-oxygenization,” a mysterious process which is recommended by the wine consultant Michel Rolland, produces wines that are approved by the wine critic Robert Parker, and therefore becomes the standard for mass producers like Robert Mondavi. As Mondavi and other giants march through Europe buying up ancient vineyards, Rolland and Parker are right behind him to standardize the product.

Rolland is described in the movie as “always laughing; you have to like him.” Indeed, the man seems bubbling over with private humor as he speeds in his chauffeured car from one vineyard to another, dispensing valued advice one step ahead of the serious, even self-effacing Parker, whose opinion can make or break a vineyard. That Parker is so powerful is proof that countless wine drinkers do not have taste of their own, because by definition there can be no such thing as a wine that everyone values equally; a great wine should be a wine that you think is great, and if you think it’s great because Parker does, then you don’t know what you like and simply require a pre-lubrication benediction.

This much I know from common sense. How many of the rest of Nossiter’s charges are true, I cannot know, but he is persuasive. He is fluent in the language of every country he visits, talks with the powerful vintners and the little local growers, visits veteran retailers, and consults with a wine expert from Christie’s, who wonders “to what extent individuality has flown out the window,” and concludes it was taken wing to a very great extent indeed.

Much is made of terroir, a French word meaning “soil” but also meaning a region, a specific place, a magical quality which a particular area imports to the grapes it produces. Every great wine should be specifically from its own time and place, in theory, but in practice that would mean that some wines were great and most wines were not, and that’s no way to run a global industry. The new goal, Nossiter believes, is to produce pretty good wine and train consumers to consider it great because they’re told it is and can find the real thing only with some difficulty. Nossiter thinks some French vineyards are holding out, but that the Italians have more or less caved in to Mondavism.

He makes this argument in a film that is too long and needlessly mannered. There is no particular reason for a restless hand-held camera in a documentary about wine. If we are watching a documentary about cockfighting or the flight of the bumblebee, we can see the logic of a jumpy camera, but vineyards don’t move around much and are easy to keep in frame. I am more permissive about Nossiter’s other camera strategy, which is to interrupt a shot whenever a dog comes into view, in order to focus on the dog. This I understand. Whenever a dog appears at a social occasion, I immediately interrupt my conversation to greet the dog, and often find myself turning back to its owner with regret.

Despite its visual restlessness and its dogs, “Mondovino” is a fascinating film, not because Nossiter turns red-faced with indignation, but because he allows his argument to make itself. There comes a point when we learn all we are likely to learn about modern wine, and the movie continues cheerfully for another 30 or 40 minutes, just because Nossiter is having so much fun. Although modern wines may have lost their magic, traveling from one vineyard to another has not, and just when we think Nossiter is about to wrap it up, off he goes to Argentina. It was certainly only by an effort of will that he prevented himself from visiting our excellent Michigan vineyards. They have some magnificent dogs.