Willfully over determined and perversely stylized, “Mommy,” the fifth directorial feature from young filmmaker Xavier Dolan was certainly an attention-getter at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where the jury obliged it to share a prize with Ye Olde Postmodernist Jean-Luc Godard’s latest, “Goodbye To Language.” To paraphrase Public Enemy, in the case of Dolan’s picture you might be well advised to look skeptically upon what is, to this critic’s eye, a hype.

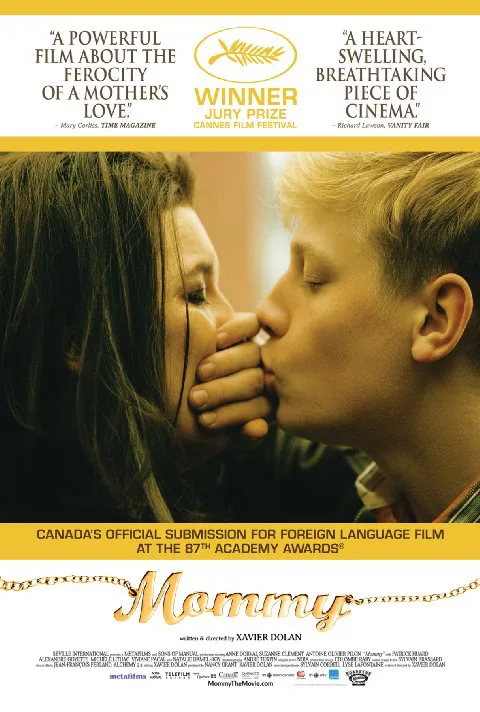

The 25-year-old Dolan, a one-time child actor who cultivates a public persona equal parts prickly and smirkily smarmy, could be intuited as French-Canadian art cinema’s answer to Justin Bieber even were he a press-avoiding recluse. It’s in the work. Here, the story (such as it is) concerns a deeply troubled teen released into the custody of his abrasive, at-loose-ends single mom, after wreaking havoc in a juvenile detention center. (The movie begins with a text proviso recounting the passage of a [fictional] Canadian law allowing parents to have children committed at will, which is the sort of thing that academics call “foreshadowing.”) The mom, Diana, calls herself “Die” and has an overly festooned keychain and wears super-short skirts and wants to get work as a translator, but not of super-long work such as that of Ken Follett (don’t look at me, that’s what she says when talking herself up to a potential client). She’s played with hardened integrity by Anne Dorval. Also excellent is Suzanne Clément as Kyla, a neighbor of Diane who takes an interest in the welfare of her son.

Less good is Antoine-Olivier Pilon as Steve, the son. One can’t be entirely sure whether it’s Pilon’s look-ma-no-control performance or the fact that Steve’s not so much a character as a construction of tics and tropes. Angel-faced but never not mugging, not particularly intelligent but always capable of a razor-sharp comeback to a perceived slight, Steve is an ideal of the anti-social. One gets the feeling that Dolan finds him admirable somehow, which rubbed this critic very much the wrong way. To the extent that as the movie trudged on, whenever some misfortune befell the boy, I found myself reminded of the notorious reactionary conservative cartoonist Al Capp’s observation that by his lights, “Easy Rider” had a happy ending.

Although he has very little sense of structure or narrative, Dolan does have a noticeable technical facility, or perhaps the ability to hire, with the help of several national arts subsidies, crew members of technical facility, whom he uses to the fullest. The first minutes of the film are replete with nifty little color tricks, focus fripperies, and lens flares. The sound mix, too, is very “Hey!” as when one song plays on the soundtrack (and yeah, I think it WAS Counting Crows) while other music leaks through Steve’s headphones. The showoffiness extends to the movie’s frame itself.

For the most part, Dolan presents the film in a 1:1 aspect ratio, a perfect square (although tricks of the eye make it look more narrow a view than it actually presents). This is even more extreme in its boxiness than the old “Academy ratio” most of us know from sound films of Hollywood up until the early 1950s. In theory this framing intends to trap the viewer into the hemmed-in dimensions of the characters’ life options, and as such, one could argue that it serves that function well. However. Dolan breaks out of it twice: once during a montage in which Steve, Kaya, and Diane start to blossom in their affinities and affections; tooling along to “Wonderwall,” Steve almost literally “opens” the frame, willing the film into widescreen and letting the imagery breathe a bit. Why it’s almost as if the “Steve Effect” the character jokingly spoke of earlier was real! Soon enough, circumstances intrude and the frame shrinks again.

The effect is of a corny but effective metaphor (and the montage itself is so full of “moments” it suggests Dolan won’t have any trouble at all adjusting to working in Hollywood once he gets there). It’s with the second widening that Dolan shows his true hand, expanding the screen’s dimensions for a dream sequence in which the actual Steve is replaced by what I’ll call Hunky Steve, who’s normal and loves his mom and gets married and gives mom a grandson, etc. Once Diane is shaken into waking, the box hems her in again, and the effect is actually sadistic: against Diane, and yes, against the audience. Dolan is not going to let you forget who’s boss. As for myself, I quit.