The Japanese author Yukio Mishima seems to have thought of his life as a work of art, and more than anyone since Ernest Hemingway he got other people to think of it that way, too. He was a brilliant self-promoter who not only wrote important novels and plays, but also cultivated the press, posed for beefcake photographs and founded his own private army. He was an advocate of a return to medieval Japanese values, considered himself a samurai, and died on schedule and according to his own plan: After occupying an army garrison with some of his soldiers, he disembowled himself while being beheaded by a follower.

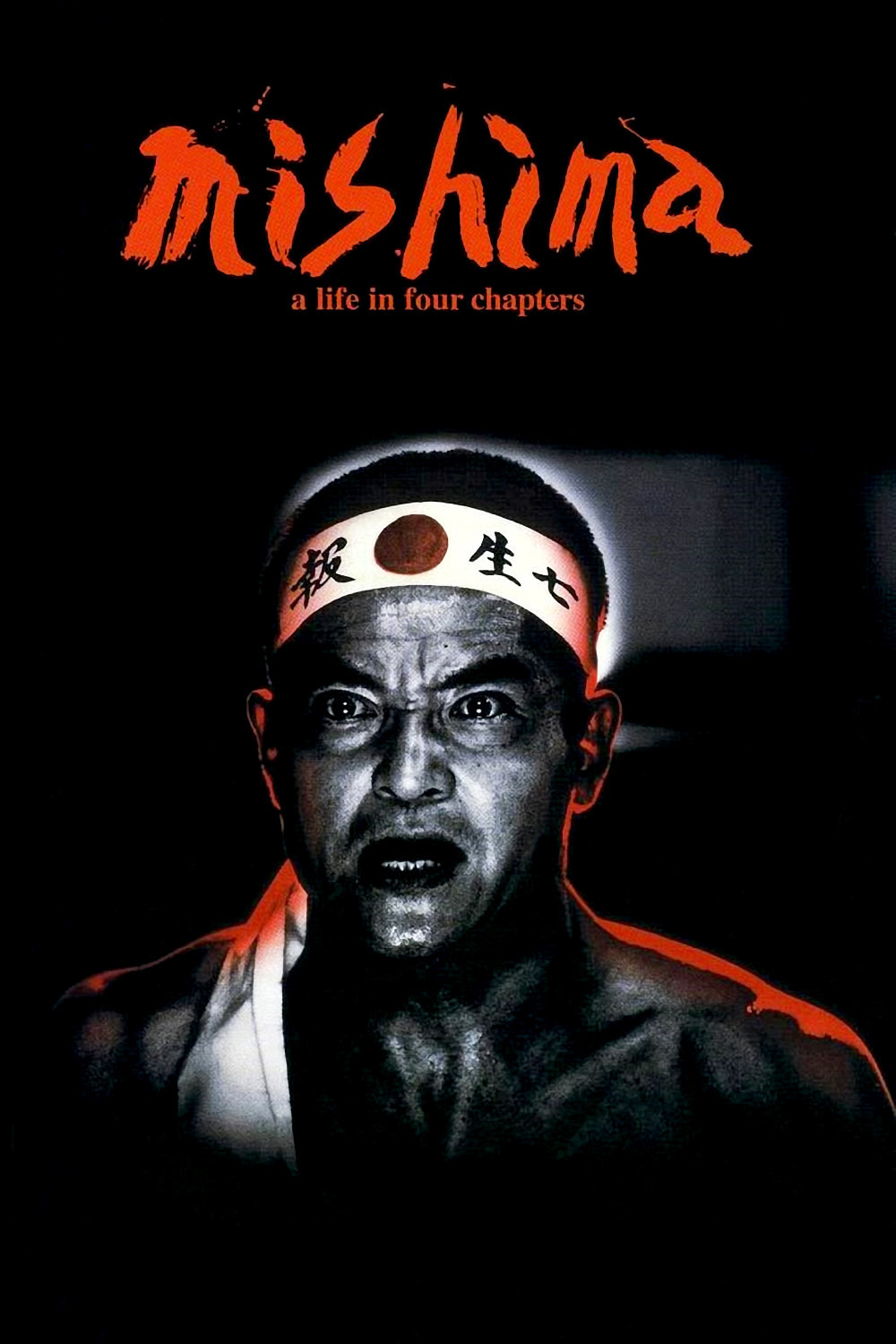

Mishima’s life obviously supplies the materials for a sensationalistic film. Paul Schrader has not made one. Instead, his “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” takes this most flamboyant of writers and translates his life into a carefully structured examination of three different Mishimas: public, private and literary.

The film begins with the public Mishima, a literary superstar who begins the last day of his life by ritualistically donning the uniform of his private army. From time to time during the tilm, we return to moments from that final day, as Mishima is jammed somewhat inelegantly into a tiny car and driven by his followers to an appointment with a Japanese general. The film ends with Mishima holding the general hostage, and winning the right to address the troops of the garrison (who must have been just as astonished as if Norman Mailer turned up at West Point). Although the film ends with Mishima’s ritual suicide, it is not shown in the graphic detail that’s popular in recent films; Schrader wisely realizes that too much blood would destroy the mood of his film, and distract attention from the idea behind Mishima’s death.

Mishima’s last day is counterpointed with black-and-white sequences showing his childhood and adolescence, and with gloriously stylized color dramatizations of scenes from his novels, Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House and Runaway Horses. The scenes from the novels were visualized by designer Eiko Ishioka, who seems to have been inspired by fantasy scenes from early Technicolor musicals. They don’t summarize Mishima’s novels so much as give us an idea about them; as we see the ritualistic aspects of his fantasies, we are seeing Japan through Mishima’s eyes, as he wished it to be.

The black-and-white biographical sequences show a little boy growing up into a complicated man. Young Yukio, raised by his mother and his grandmother, was lonely outcast with a painful stammer, and we can see in the insecurities of his youth the impulses that led him to build his muscles, to leap for literary glory and to wrap himself in the samurai ethic.

“Mishima” is a rather glorious project, in these days of pragmatic commercialism and rank cynicism in the movie industry. Although a sensationalized version of his life might have had potential at the box office (and although Schrader, author of “Taxi Driver” and director of “American Gigolo,” would have been quite capable of directing it), this is much more ambitious and intellectual film. It challenges us to think about Mishima instead of simply observing the strange channels of his life. What did he prove, on the day when his life ended according to plan? That he was willing to pay the ultimate price to transform his life into an artistic statement – and also, perhaps, that some of his genius was madness. Was it worth it? Who can say who is not Mishima?