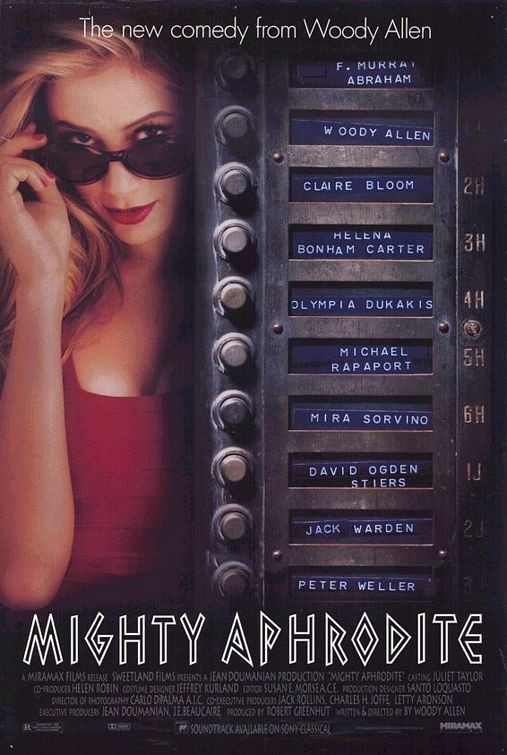

Woody Allen‘s new comedy “Mighty Aphrodite” opens with a Greek chorus, standing in an ancient amphitheater and uttering dire warnings about those who would tempt fate. Indeed one of the tempters is Woody Allen himself, whose recent life has sometimes seemed drawn from Greek tragedy, especially as it applies to those who would kill their wives and marry their daughters – or, because we are more prudent in the 20th century, divorce their wives and date their adopted daughters.

That Allen would venture into this subject matter seems fraught with risk. But “Mighty Aphrodite” quickly turns into safer waters and develops into a sunny comedy about tawdry people. Allen plays a New York sportswriter named Lenny, unhappily married to a gallery owner (Helena Bonham Carter), who thinks their marriage might be saved if they adopt a child. Lenny is adamantly opposed to adoption, but soon finds himself cooing over an infant son named Max.

Max grows up smart. In a scene where he’s teaching the kid to shoot baskets, Lenny asks him what he wants to be when he grows up. “An interior decorator,” he says. “Only kidding.” Soon Lenny becomes convinced that the boy’s birth parents must be brilliant. As his marriage collapses and his wife embarks on an unhappy affair, Lenny begins an obsessive search to track down Max’s origins, and eventually discovers that the boy’s mother is a hooker and sometime porno starlet with a lot of names, one of them Linda (Mira Sorvino).

At least it isn’t complicated to meet a hooker. Lenny picks up the phone and is soon visiting a blond with a high-pitched voice, who towers over him as she leads the way into an apartment that seems to have been decorated out of a sex novelty shop (even the tropical fish have their own phallic bubbler). Sorvino’s performance in this role is intriguing because, while never compromising Linda’s exaggerated mannerisms, she subtly grows more sympathetic, until by the end we care for her, even though we still can’t believe our eyes, or ears.

Linda of course thinks Lenny is there for sex, and there’s a wrestling match with Allen playing one of his favorite roles, the shrimp overwhelmed by a strong woman. Linda, who has a colorful and descriptive vocabulary, never takes off her clothes in the movie, but there are few sexual possibilities she leaves unsuggested. Allen seldom uses the words in Linda’s vocabulary in his movies, but here they take on a certain detached innocence, as if they have an existence apart from what they describe.

The movie reveals its serious undertones (with commentary by the Greek chorus, which occasionally breaks into song and dance) while at the same time developing a plot that lends itself to slapstick. Lenny, never revealing his real reason for seeking out Linda, quickly becomes her friend and counselor, and sets about finding a nice guy for her to marry. After all, Max’s mother shouldn’t be selling it. Lenny suggests a young boxer he knows, a potato farmer from upstate named Kevin (Michael Rapaport), who is a good kid but not very bright. (When Lenny tells him Linda starred in “Schindler's List,” he vaguely remembers the film: “Yeah, that was the one about the Jews, and . . . uh, who were the bad guys again?”) Although the Greek chorus might seem an unwieldy addition to a Woody Allen comedy about modern Manhattan neurotics, the addition actually functions nicely. Chorus members including F. Murray Abraham, Olympia Dukakis and David Ogden Stiers make dire observations about the decisions Lenny is making, and their ironic counterpoint helps Allen get away with some of the more obviously mechanical plot developments. By the end of the movie, when the deus ex machina arrives from the sky in a helicopter, it seems like an inspiration instead of what it is, a convenient plot device.

Allen’s movies sometimes end on a minor note. Not this one.

Through developments that I will not reveal, he brings us to a postscript set a few years later, when Lenny and Linda meet again, and there is a bittersweet development in both of their lives, although each of them is aware of only half of it. The movie’s closing scene is quietly, sweetly ironic, and the whole movie skirts the pitfalls of cynicism and becomes something the Greeks could never quite manage, a potential tragedy with a happy ending.