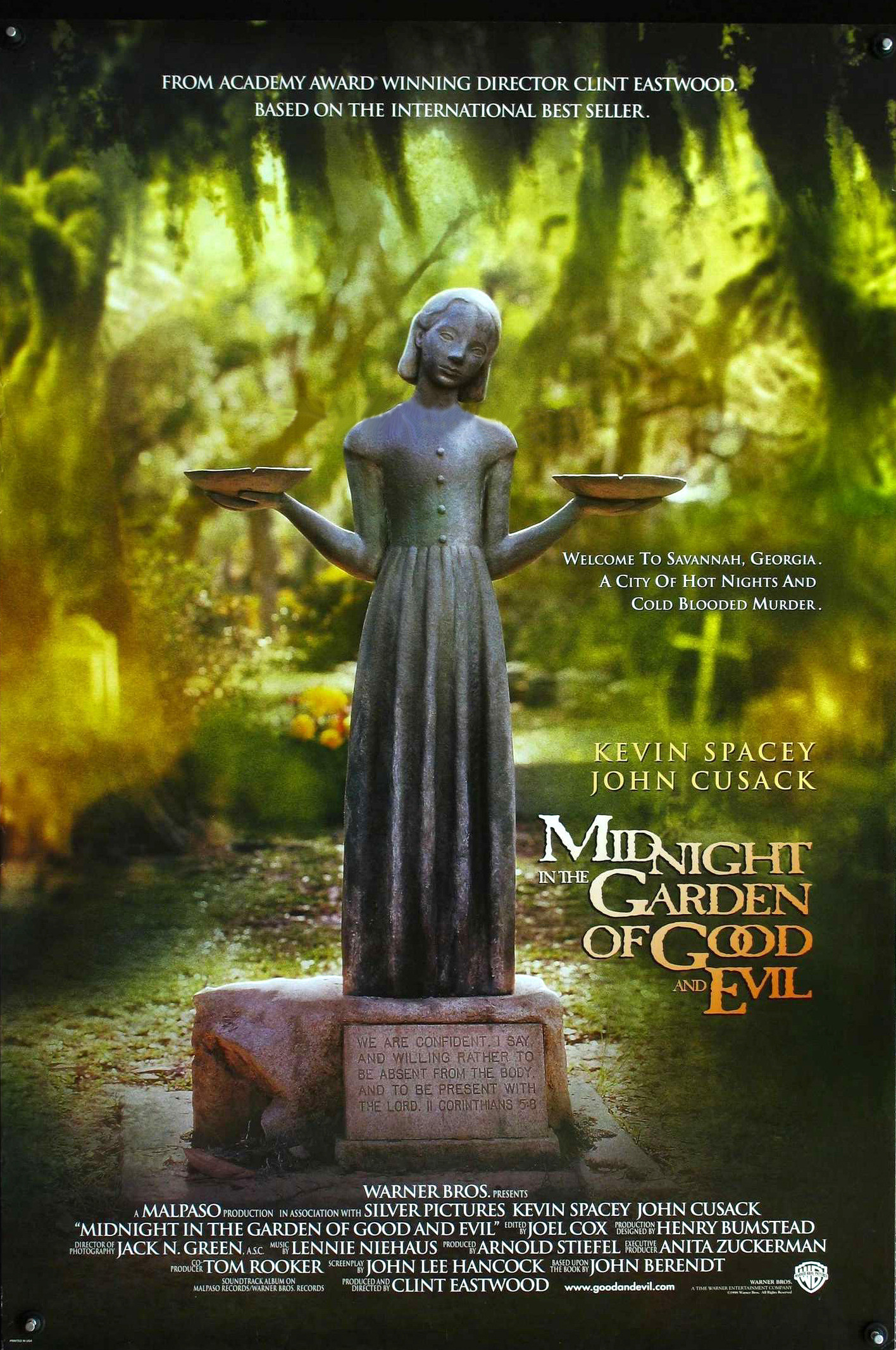

“Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” is a book that exists as a conspiracy between the author and the reader: John Berendt paints a portrait of a city so eccentric, so dripping with Southern Gothic weirdness, that it can’t survive for long when it’s removed from the life-support system of our imagination. Clint Eastwood’s film is a determined attempt to be faithful to the book’s spirit, but something ineffable is lost just by turning on the camera: Nothing we see can be as amazing as what we’ve imagined.

The book tells the story of a New York author who visits Savannah, Ga., is bewitched, and takes an apartment there. Gradually he meets the local fauna, including a gay antiques dealer, a piano bar owner of no fixed abode, a drag queen, a voodoo priestess, a man who keeps flies on leashes, a man who walks an invisible dog and the members of the Married Women’s Card Club. The plot grows labyrinthine after the antiques dealer is charged with the murder of a young hustler.

Berendt introduces these people and tells their stories in a bemused, gossipy fashion; he’s a natural storyteller who knows he has great stories to tell, and relishes the telling. He is not, however, really a major player in the book, and the movie makes a mistake by assigning its central role to a New York writer, now named John Kelso, through whose hands all of the action must pass.

There is nothing wrong with the performance by John Cusack except that it is unnecessary; if John Lee Hancock’s screenplay had abandoned the Kelso character and just jumped into the midst of Savannah’s menagerie with both feet, the movie might have had more energy and color. Or if Kelso had been a weird character, too, that might have helped; he’s written and played as a flat, bland witness, whose tentative love affair with a local temptress (Alison Eastwood) is so abashed we almost wonder if he’s ever dated before.

Berendt’s nonfiction book (the credits inexplicably call it a novel) circulates with amusement and incredulity among unforgettable characters. But the screenplay whacks the anecdotal material into shape to fit the crime-and-courtroom genre.

A doped-up young bisexual hothead (Jude Law) is introduced in two overplayed scenes, and then found dead on the floor of antiques dealer Jim Williams’ office. His death inspired an unprecedented four trials in real life, which the movie can be excused for reducing to one–but as the conventions of courtroom melodrama take over, what makes Savannah unique gradually fades out of the picture. Jack Thompson gives a solid performance as Sonny Seiler, the defense attorney, but he’s from John Grisham territory, not Savannah.

The characters in the book live with such vivid energy that it’s a shame we see them only in their relations with Kelso, the quiet outsider (there’s hardly a scene in the movie of the locals talking to one another without the Yankee witness). Kevin Spacey plays Williams, who holds two Christmas parties–one so famous that Town and Country magazine has assigned Kelso to cover it, and another, the night before, “for bachelors only.” Spacey’s performance is built on a comfortable drawl, perfect timing, a cigar as a prop and the Oscar-winning actor’s own twinkling warmth: We like Jim Williams so much that we are surprised we don’t see more of the character. “What money I have,” he explains, “is about 11 years old. Yes, I am nouveau riche– Kelso also encounters the Lady Chablis, a drag queen played by the real Lady Chablis, who specializes in shocking the bourgeoisie. She has some one-liners that are real zingers, but her big scene–crashing the black debutante ball to embarrass Kelso–is a scene so lacking in focus and structure that it brings the movie to a halt. My guess is that the Lady Chablis would be well known to the black middle class of Savannah (where everybody knows everybody), and the blank stares she gathers make you realize the scene lacks setup, purpose and payoff.

Another colorful character in the book is Joe Odom (played in the movie by Paul Hipp), who makes himself at home as an unpaid (and unauthorized) “house-sitter” in historic mansions, supporting himself as the host of the longest-running house party in Georgia. He’s a charmer who has the misfortune to be dating Mandy Nichols (Alison Eastwood), and so the movie has to hustle him out of sight to free Mandy for her frictionless dalliance with Kelso–who mutters vaguely about his “track record” in romance, and has to be instructed to kiss her after their first date. What’s the point? Much is made of Minerva (Irma P. Hall), the voodoo priestess, who casts hexes against the prosecuting attorneys and leads midnight forays into local cemeteries. In the book some local residents, Jim Williams included, halfway believe in her magic; in the movie, she comes across more as a local eccentric.

In a way, the filmmakers faced the same hopeless task as the adapters of Tom Wolfe’s “The Bonfire of the Vanities.” The Berendt book, on best-seller lists for three years, has made such a vivid impression that any mere mortal version of it is doomed to pale. Perhaps only the documentarian Errol Morris, who specializes in the incredible variety of the human zoo, could have done justice to the material.

Still, I enjoyed the movie at a certain level simply as illustration: I was curious to see the Lady Chablis, and the famous old Mercer House where the murders took place, and the Spanish moss. But the movie never reaches takeoff speed; its energy was dissipated by being filtered through the deadpan character of Kelso. They say people who hadn’t read “The Bonfire of the Vanities” liked the movie more than those who knew the book. Maybe the same thing will happen with “Midnight.”