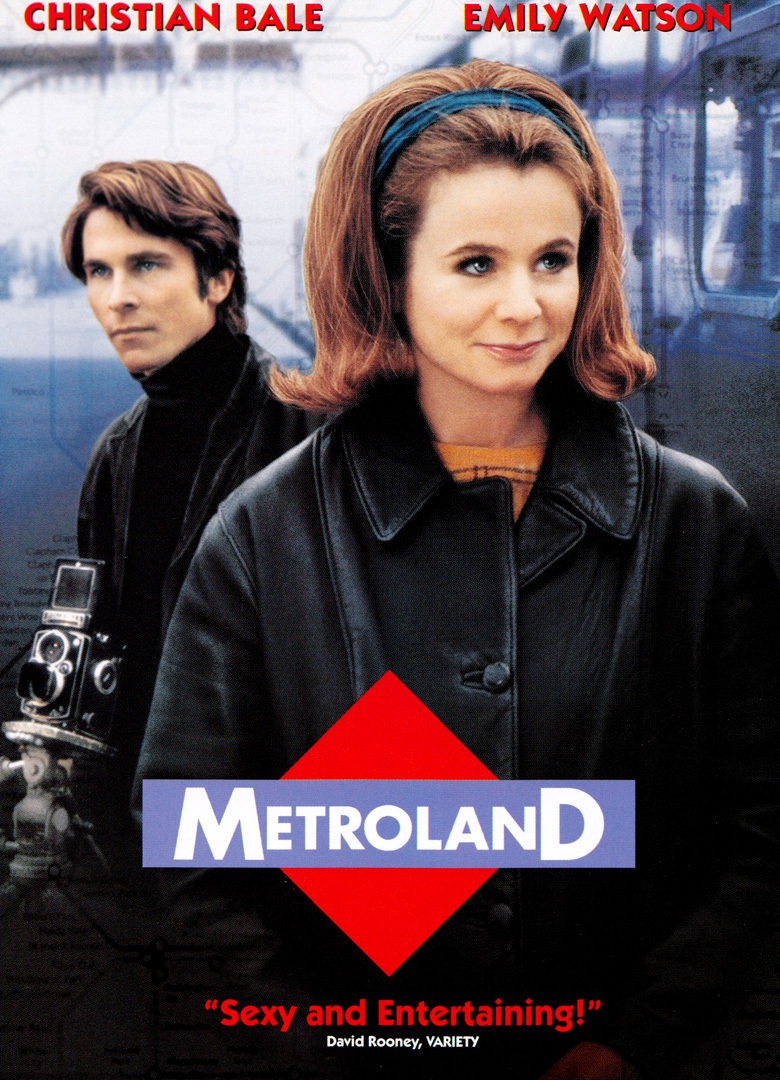

There are a lot of movies about escaping from the middle class, but “Metroland” is one of the few about escaping into it. In 1968, Chris is a footloose British photographer in Paris, who has an affair with a French woman and drifts through streets alive with drugs and revolution. In 1977, Chris has become a married man with a child, living in a London suburb at the end of the Metropolitan line of the Underground. Is he happier now? Not according to his friend Toni, who joined Chris in ’60s hedonism and never looked back. Toni (Lee Ross) has just returned from America, after dropping out in Africa and Asia. He’s returned to the United Kingdom for one reason: To persuade Chris (Christian Bale) to leave his family and join him on the road. “Metroland,” based on a 1980 novel by Julian Barnes, who became famous after Flaubert’s Parrot, watches Chris as he is enticed by temptation and memory.

The memories are often about the two women he met in Paris that year–the one he married, and the one he didn’t. Annick (Elsa Zylberstein) is one of those young Parisians who live on air and use the cafes as living rooms. They meet, they flirt, they become a couple. The soundtrack of their romance is ’60s rock, mixed with Django Reinhardt, and with Annick he learns about sex (“Is it the first time?” she asks, with reason). Then into his world drifts a visiting English girl, Marion (Emily Watson), who is sensible, cheerful, supportive, reassuring and wholesome. She sizes him up and informs him that he will get married, probably to her, because “you’re not original enough not to.” He does, and life in Metroland continues happily until Toni calls at 6 a.m. one morning. Toni tempts Chris with tastes of the life he left behind, and at a party they attend, an available girl makes him an offer so frank and inviting he very nearly cannot refuse. Yet the movie is not about whether Chris will remain faithful to Marion; it’s about whether he chose the right life in the first place.

Philip Saville, who directs from a screenplay by Adrian Hodges, starts with a straightforward story of life choices (the plot could as easily be from Joanna Trollope as Julian Barnes) and slips in teasing asides, as in a scene where Toni almost has Chris and Marion believing he has “always been in love with Chris.” Or when Chris daydreams about Marion telling him, “of course, I expect you to have affairs.” What Saville doesn’t do, mercifully, is depend on sentiment: Chris is not asked to make his decision based on loyalty to wife and daughter, but on the actual issue of his choice to live in the London outskirts and raise a family. There is a cold-blooded sense in which he could decide, objectively, dispassionately, that he took the wrong turning–that it is his right to join Toni in a life of wandering, sex and mind-altering.

What’s curious, given how everything depends on Chris, is the way the movie is really centered on the two women. Annick almost deliberately plays the role of a cliche–the brainy, liberated French woman showing the Englishman the sensual ropes. Zylberstein finds the right note: the woman proud to have “a beautiful British boyfriend” and hurt when she’s dumped, but not blinded by dreams of eternal love. And then there’s Marion, played by Emily Watson in a radical departure from her tormented characters in “Breaking the Waves” and “Hilary And Jackie.” Here she is cheerfully normal–an ideal wife, if that’s what Chris is looking for. “No wonder you’re bored,” says Toni. But why did Toni come back, if he wasn’t bored, too?