The 93-year-old master documentarian Frederick Wiseman is often described as a filmmaker whose specialty is depicting the inner workings of institutions of varying sizes, and the way they evolve and change over time, whether it’s an army base, a mental hospital, a domestic violence shelter, a small town in Maine, a neighborhood in Queens, the New York Public Library. And it’s true: that is probably the most obvious through-line in Wiseman’s work.

But Wiseman should be treasured for many other reasons, and the biggest one is the simplicity and purity of the filmmaking itself. The very best documentaries are not content to explain something or tell a story. They capture moments in life and some elusive, perhaps previously unnamed truth about living. They help you see through fresh eyes and understand things you never thought about or took for granted. They’re also often astute in showing the details of the act of creating something, whether it’s being demonstrated by artists (as in a string of French documentaries, including “Crazy Horse,” “Ballet,” and “La Comédie-Française ou l’Amour joué”) or the workers and/or citizens in other documentaries trying to serve their clients or community, or just get through the year and into the next one.

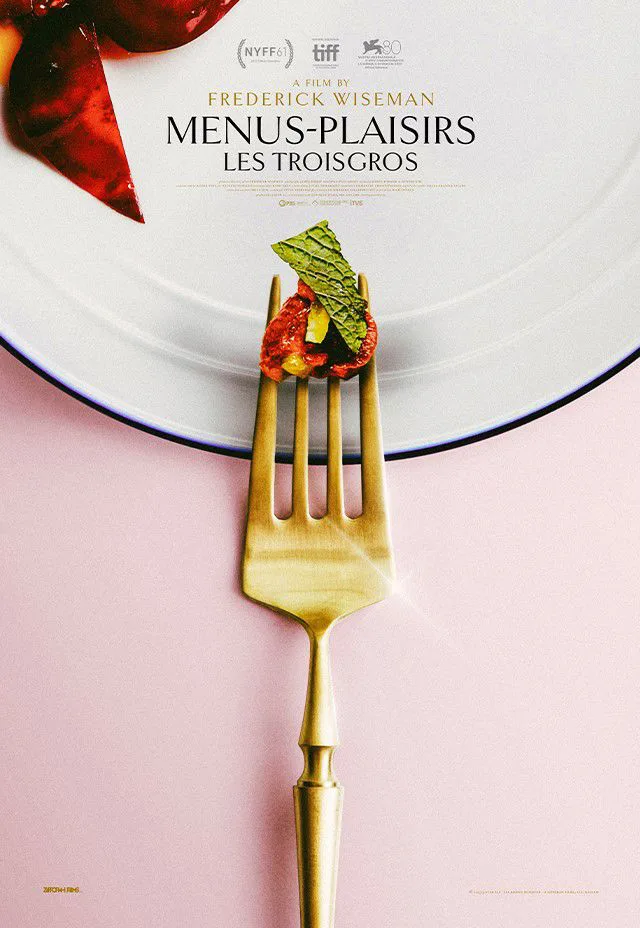

“Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros,” a documentary about a restaurant in France, puts all of these aspects of Wiseman’s gifts on full display. The result is one of his simplest yet richest works. It’s one of the great films about food and cooking, right up there with “Big Night” and “Tampopo,” an equally great “process” movie that shows the inner workings of a fine dining restaurant, from the initial purchase of produce and meat and fish to its preparation, plating, and service; a film about families, and family businesses; and, subtly but perhaps most strikingly, a film about what it means to look, really look, at a thing, and appreciate it for what it is, whether it’s a bunch of carrots or radishes in a produce market stall, a flowering shrub in a field, a herd of cows grazing, a mass of bees in a hive, or configurations of employees and supervisors moving delicately around one another in a restaurant kitchen.

The main setting is Le Bois sans Feuilles (translation: “The Forest without Leaves”), a restaurant with three Michelin stars that was located in an urban setting in Roanne for decades (across the street from a train station) but moved in 2017 to a manoir in nearby Oaches and adopted a more “countryside” vibe. The place is run by the Troisgros family, which owns two other restaurants in the area. The customary Wiseman fascination with change over time is incarnated in the relationship between the current patriarch of the family, Michel, his heir apparent César (there’s a brief mention of Michel’s younger son, Léo, a chef at another restaurant who seems exasperated when his father suddenly changes the sauce for a dish he’s been perfecting for three weeks).

It takes a while to discern that César and Michel are related, as they interact mainly as boss and employee (though cordially and with mutual respect). As is always the case in Wiseman’s work, there are no talking head interviews in the film, no identifying “chyrons” or titles to tell you everyone’s name and position, no voice-over narration, indeed none of the devices you now expect to see in all documentaries, regardless of subject or style. (However, Wiseman does find a workaround to his “no narration” rule: he’ll often have a subject ask another person to verbally explain an idea or process, then watch and listen.)

Occasionally, a restaurant employee or customer will say someone’s name, but it’s rare. Wiseman is keen on finding ways to get us to appreciate people only through what they say and do, as well as their relationship to the spaces they move through and work or live in, and then infer their relationship to the world at large. There are mini-montages between scenes or sequences in the film, often consisting of tight closeups and wide shots that hang onscreen long enough to appreciate the image’s texture, color, and content. There’s movement in the cutting, often conveyed by choosing a series of shots where people move laterally across the screen in the same direction.

But the vast majority of “Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros” finds Wiseman and his cinematographer James Bishop finding a good spot to observe two or three or many more people doing a thing and parking the camera there. The result is a series of moments rich enough to feel like a short film unto itself. There’s an explanation to a couple of diners about the use of sulfite in winemaking. There’s a section where a cheesemaker takes restaurant employees on a tour of his factory and explains the chemical processes of ripening (“Each cheese has its moment of truth, and that’s when you sell it”). A farmer tells Michel about the lactation cycles of goats and how it relates to his business. There’s a sequence showing how honey is extracted from a beehive.

Something about the way Wiseman shoots, cuts, and positions these moments encourages the viewer to draw connections between it and other parts of the film (as in the beehive scene, which might make you think back on the wide shots of the kitchen with all the “worker bees” moving around each other as they work together). But this, too, is all about inference. Wiseman never hands you anything, never grabs the back of your neck, turns your head, and says, “Now look here.” That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with making a movie that way—not at all!—only that Wiseman doesn’t do it, and that refusal is part of what makes his films stand apart.

Another thing is the frequently massive run-time of Wiseman’s films, which you just have to surrender to. A scene will go on as long as the movie feels that it needs to. It’s not looking at the clock, so you shouldn’t, either. But if you stay focused during scenes that feel as if they’re playing a bit too long, you might notice that part of the strategy is to let you observe a tighter, momentary kind of evolution: the way a conversation or other exchange will start out one way and end up another way.

For instance, there’s a long scene about two-thirds of the way through where Michel eats a dish César has overseen, and they have a long discussion about what Michel thinks is missing from it: a visual element, not a taste element. Michel appreciates that there are “no hangers-on softening the taste of the sauce” and says he finds the flavor “very nice,” then adds, “but to look at?” A big part of the restaurant’s fame originates in its presentational brilliance. Every dish is plated like a painting in a circular frame, every element on the plate compositionally and color-balanced, but never in a way that fights or undermines the taste and texture. You can feel César resisting these notes slightly, then giving in. Whether it’s because he’s realized dad was right or because dad’s the boss is for us to figure out.

At one point, Michel says of the restaurant that “it’s always in movement.” He’s talking about the menu and the place itself, and we might expand that thought to include the lives of everyone who works there and the process of making art. Wiseman believes that food can be an artistic medium, although ephemeral by nature, like theater (which he also does). You make something beautiful, then it is destroyed as it is consumed. The cycles of destruction and creation are incarnated every day in restaurants. Watching this movie made me realize why people take pictures of their food: they want a record of the beautiful object that’s about to disappear.

Now playing in theaters.